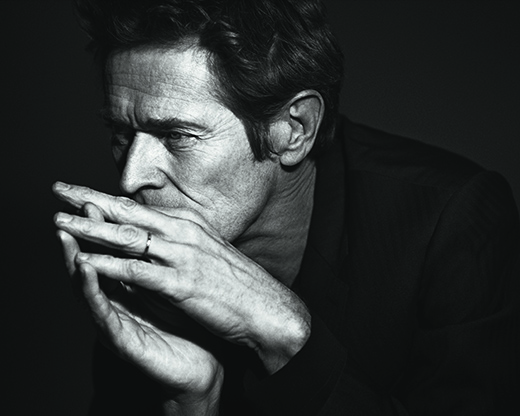

This interview took six months to do. It was done in two different countries, over two different time zones, scheduled and rescheduled numerous times through various assistants. It had to be worked around tour dates, Grammy rehearsals and Oscar press. It’s without a shadow of a doubt that I can declare Hans Zimmer the Hardest Working Man in Show Business. And I should know, because I’m his daughter.

If you’ve been to the movies at all in the past 20 years you’ll have heard a Zimmer score—they’re hard to miss. After doing some light Googling I’ve found that my father has worked on close to 200 movies since the mid ’80s—everything from The Lion King to The Dark Knight. Action, drama, romance, comedy, animated, good, bad, big, small, he’s done them all. And I’m fairly certain he’ll keep doing them all until he drops dead at the keyboard.

He is not your average father—or your average composer. And he’s definitely not your conventional human being. His work, his music, is what gets him out of bed and down the stairs every morning and keeps him in a studio until the early hours of the following morning. What he does is who he is, and I’m immensely proud of him.

My dad is my favorite person to have a long chat with about life and work and everything in between. The following conversation is just one of our many… except this time it’s on the record.

ZOE ZIMMER: OK, this thing is recording now, so let’s both try to keep the swearing and bad jokes to a minimum, yeah?

HANS ZIMMER: That’s asking a lot…

ZZ: No shit. OK, but really, let’s talk about some stuff. Let’s start easy: Where do you consider home?

HZ:Nowhere.

ZZ: Jesus, really? I guess that wasn’t starting easy after all.

HZ: Yeah, seriously. It’s something that really bothers me. I don’t know… I think language is partly home.

ZZ: Does it bother you that none of your kids speak German?

HZ: No, but it bothers me that none of my kids have the same accent as me. Anyway, I think if I had to go and declare a place “home,” it would be England, but I don’t think the English would ever see me as one of their own. Home… I don’t know, I’m a traveler, I suppose. I’m a gypsy in a funny sort of way. It’s wherever the project is, y’know? It’s wherever there are musicians I want to play with. Look, at the end of the day, I’m an entertainer, the way musicians always have been, and we just go from place to place wherever people want to hear our music.

ZZ: Well, for a long time you were definitely based in L.A.

HZ: Well, “based” is different from “home.” I suppose my studio is home. I mean, my room is more a home than a studio.

ZZ: That studio’s kind of been everyone’s home at one time or another. I know it has been for me. I mean, I basically grew up in the back of a recording studio.

HZ: Right, exactly and you didn’t turn out so bad! The thing about the studio is that it’s an interesting place full of interesting people, and that should always make you feel at home. It’s full of possibilities, and there’s a creative dynamic that goes on there. There’s kind of a weird sense of community, but it’s not a community in the normal sense of the word. I mean, everyone’s ego is pretty big.

ZZ: Really big.

HZ: And everyone’s a little bit odd…

ZZ: Really odd. But really great.

HZ: And I think the only thing that we all really have in common is not so much even the music, it’s really just that none of us would be able to get a job anywhere else.

ZZ: Right, you’re really all just a big band of outcasts who got lucky.

HZ: Precisely.

ZZ: And there are a lot of outcasts right now—I mean, the studio is just getting bigger and bigger. It might be your home, but it’s also the size of a small village. Do you think it’s just going to keep growing? Do you want it to keep growing?

HZ: No, I think we have enough buildings now, don’t you?

ZZ: I think if there were anymore buildings you would have to start handing out Segways or small ponies for people to get around.

HZ: Definitely small ponies. But you know, I like people moving in and out of there. I like the atmosphere changing and people progressing. What I love is when people get their own careers together, and then they leave and they do their own versions of it, y’know?Like Harry [Gregson-Williams, Shrek] and John [Powell, How to Train Your Dragon] and people like that. And I like new people coming in; I think it’s interesting. I think it’s interesting that I created this little magnet that draws people in from all over the world, and sometimes it works out and sometimes it doesn’t, but it’s always interesting.

ZZ: Does it piss you off when people question the way the studio works? In terms of having people write for you—you know, when it’s made out to be Hans Zimmer’s Musical Sweatshop?

HZ: Well,they can’t have it both ways. Because on the one hand I get knocked for “sounding the same,” which of course doesn’t actually make any sense—look at the films I did with Ridley [Scott], and that’s just one filmmaker: Thelma & Louise doesn’t sound anything like Gladiator, which doesn’t sound anything like Black Hawk Down, which doesn’t sound anything like Hannibal, which doesn’t sound anything like Black Rain, which doesn’t sound anything like Matchstick Men…

ZZ: I really liked Matchstick Men.

HZ: So did I, but I think we were the only ones. So anyway, on the one hand there’s obviously a very strong imprint in the architecture of the studio, and on the other hand… I mean, you already know all of this. I write these pieces and they’re very complete, everything’s done on them—the orchestration, everything. But like everybody, I need assistants. I’m the architect, but I need a couple of bricklayers, y’know? Do you think Michelangelo painted every square inch of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel? Probably not—it would have killed him if he had to do it all by himself!

ZZ: Fair enough. So do you think people who make those assumptions are just uninformed about the system? Because assisting and writing additional music is basically how you get your foot in the door, right?

HZ: Well, yes and no. It didn’t really used to be like that. When I got to Hollywood it was slightly different. The studios had orchestrators and arrangers on staff, and they never really got credit for anything. They were just “Backroom Boys.” So now I really do fight for credits for people, even really small credits. It’s important to me that people get to participate, and that they get credit and that they are visible, so I really do fight fort hem. They might not be the architects, but it’s still their time that they give me, that they give to these projects.

ZZ: Interstellar was all you though, wasn’t it?

HZ: All me. Interstellar nobody got to write a single note on other than me. And although a lot of musicians played on it, one of the things we tried to preserve was the singularity of my touch and my vision, and literally me playing every note. I mean, on all of these scores I have at one time or another played every single note. But unfortunately the story of me just sitting there by myself and writing is far less exciting and scandalous than the idea of assistants and ghostwriters.

ZZ: Talking about all this always makes me wish I played an instrument. I thought that the other day when I saw Whiplash. I mean, you really hogged all the musical talent in the family. Do you ever wish any of us, your kids, were more musical?

HZ: No. I love that you are all musical imbeciles.

ZZ: Whoa whoa whoa. Hey now…

HZ: No, what I mean is, I think it’s really hard tofollowinthe footsteps of anybody. And I think it’s really important that you go and make your own path. What I say to all of you is “follow your dream,” but at the same time I’m saying “don’t be stupid.” There are all these people who think following a dream means that you have to be some big star or something. All I’m saying is if you want to become a great plumber, or a great chef, or a great whatever, then do it. Just be a great you, and don’t take no for an answer.

ZZ: I know. You’ve always said that. You’ve always been very supportive of whatever I’ve wanted to do. And yeah, of course it can be daunting being related to someone who’s not only successful, but so successful in such a creative industry. Growing up with that made me feel like it wasn’t about finding a job, it was about finding a passion.

HZ: I know, but I try to be a shining example to you—to all of my kids—that the impossible is possible. Having a passion for something is a tricky thing. There are many ways of going about that passion—you can make it your job or you can make it your hobby, and both are equally valid. You got one life, it ain’t that long, so you may as well…

ZZ: Make it count? Have a good time? Don’t fuck it up?

HZ: Yeah, but more than a good time. Get real pleasure out of it, not just fun. Feel it all, have conflict, have difficulties, suffer for it a little bit, y’know?

ZZ: God, that’s so German of you.

HZ: Yes! But you need it. When your mum and I were first together the electricity used to always get turned off because I wouldn’t pay the bill, and it’s really hard to be an electronic musician with no electricity! But yeah, I know a lot of really talented musicians who will never really make it, because people realized they were talented early on so there wasn’t enough opposition. And you need that, you need friction, you need struggle. Life needs to scare you sometimes; you have to respect it and be in awe of it. So yeah, be a little scared, let it freak you out. I don’t know, maybe you shouldn’t be listening to my advice.

ZZ: No, I always like your advice. Even if I don’t always listen to it. In fact, one of my favorite bits of advice from you was: “Remember, nothing’s less attractive to a man than a weeping woman.”

HZ: [Laughs.] It’s true! It’s true! That’s some great fatherly advice! I try to be useful, y’know? We have good chats, right?When we’re together, I try to give everything there is, I try to come up with ideas…

ZZ: You are useful. I always say that I’d rather have you be the father you are now, rather than the father you weren’t when I was growing up, y’know? You were terrible at playing Barbies, but if I’m having trouble with work? Breakup with a boyfriend? Need to know where to buy the best macaroons? You’re the first person I call.

HZ: Oh, man. The Barbies…

ZZ: I know, you still have Barbie PTSD. Sorry. Let’s talk about something less traumatic. Do you get bored? I sometimes worry you get bored of writing for (insert name of generic comic book movie sequel/prequel).

HZ: Bored? No, not bored. You know, all those big movies still bring me something, they still bring a challenge. Whether it’s Spider-Man or Superman or whatever, I strive to do something different everytime. And I get to work with new people, new musicians who have a fresh take on it all, even if it is a sequel. And I try to do new things too, like the shows last year. [Zimmer played two live shows in London at the Eventim Apollo in October 2014.] That was new, it was exciting, and terrifying—I mean, you know how petrified I get about going on stage.

ZZ: Yeah, but only a few of us know. You always pull it off. And you always have a great time in the end, right? If you don’t then you fake it really well. You looked like you were having the time of your life at the Grammys with Pharrell…

HZ: I do have a good time, despite the fear. After the first show in London, which was terrifying, I thought maybe the stage fright would get better on the next night. I thought maybe I would learn something, but of course it wasn’t better. And I realized that it’s not about it “getting better,” that’s just how I’m built, y’know? I get freaked out. So just do it. Do it despite everything else, because if I don’t do it I think it would be something I would regret.

ZZ: So what do you wanna do now?

HZ: I sometimes wish I could just watch an awful lot of television in bed and not engage in the next battle, y’know? But I can’t, you know I can’t. I think part of what happens is—I don’t think there’s any middle ground. I think you’re either very successful or you’re not successful at all. I think if you’re in that middle ground then the magnetic pull is always to the bottom. I think being a guitarist playing songs in a subway station and doing a hundred-million-dollar movie are equally great. But the slithering around in the middle is not so great. And the middle ground is really where the sharks swim. They don’t swim at the top or the bottom—all the uninspiring people you don’t want to hang out with are in the middle ground.

ZZ: Do you remember telling me what the Four Stages of a Career were? “1. Who is Hans Zimmer? 2. Get me Hans Zimmer. 3. Get me someone who sounds like Hans Zimmer. 4. Who is Hans Zimmer?”

HZ: [Laughs—a lot.] Right!

ZZ: Do you worry about what stage you’re in?

HZ: Nah, not really. I’m not done, y’know? I still have more to say.

ZZ: Well, yeah, you’re not really the type to retire and move to Florida.

HZ: No way. Musicians don’t think about retirement. My hero is [the late British comic magician] Tommy Cooper, for all sorts of reasons. For his humor, for his crazy fez, for his courage for going out on the stage and failing. His jokes going wrong, his magic tricks going wrong, and mainly for having a laugh at himself. Even his death, people weren’t sure it was real for a while. And he died doing what he loved, he died in the place that he loved… standing on a stage.

ZZ: Don’t get any ideas…

HZ: That’s just it—I’m going to be here until the ideas run out.

ZZ: Glad to hear it, Daddy. Now let’s go get some dinner.

—