Behind-the-scenes videos accompany most Teen Vogue fashion shoots. In them, young celebrities usually talk casually and endearingly about childhood, their personal style (to whatever extent they understand it) and what it’s like to work with Scarlett Johansson or attend red carpet events. They speak as images of them in gorgeous, perfect clothing, posing and negotiating on set, move across the screen.

In a behind-the-scenes video from April 2012, actor Josh Hutcherson, who comes from Union, KY, and costarred in the Hunger Games, says he never attended a real prom. “I went to a homeschool prom once,” he says, “which, as exciting as it sounds, was a bunch of homeschool kids in Kentucky.” He’s speaking in a voice-over as we see him exit an art deco elevator with teenage girls in flapper dresses on each arm. He wears a Thom Browne New York jacket, white with black trim. “We went to the local church, and stood awkwardly while they played music and that was the extent of that.”

In another video from February 2012, 13-year-old Elle Fanning wears a red Valentino dress and stands on a mid-century modern deck with her hand on a glass door. She has a gold Oscar de la Renta cuff on her left wrist and you can see a misty view of the L.A. cityscape behind her. But what you hear her saying is, “She hates when I steal her clothes.” She’s talking about her older sister, actress Dakota Fanning. “Like that’s our number one fight, if I go in there and sneak or steal a shirt or something.”

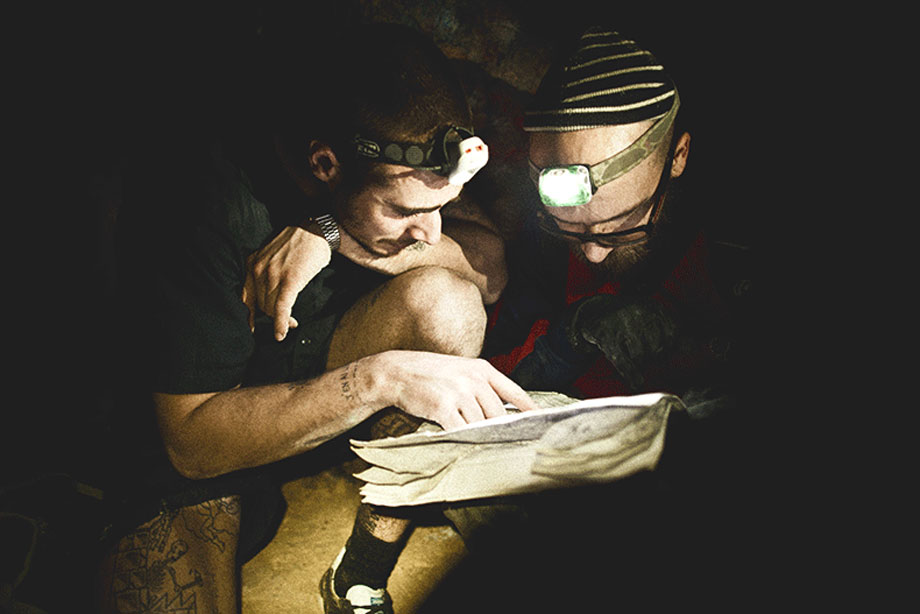

“I adore Elle Fanning,” says stylist and fashion editor Lawren Howell, who, with the help of her assistant, chose Fanning’s red dress and Hutchinson’s classic dinner jacket, clothes that give the two actors sophistication without undermining their freshness. You don’t see Howell in either video—or, if you do, it’s so fleeting you would barely notice—but her hand is in each shot. Weeks in advance, she begins researching, collecting vintage images, paging through books of photographs by Richard Avedon or Bruce Weber. She begins to construct a story that the shoot could tell—not a tight narrative, more a loose collection of scenarios and sensations. Then she collects the clothes and accessories.

“It’s like a scavenger hunt,” Howell says, of finding the right combination of prints and textures. “I work with the clothes for a week before the shoot,” she continues. By the day of a shoot, she has become intimately familiar with her material.But then everyone arrives—the photographer and his team, the celebrity subject—and careful planning can go up in smoke. “We all come together, and we all have different ideas. Just the word ‘sexy’ can have a different meaning to everyone,” says Howell.

“When I started styling on my own, I worried I’d never get any credibility if people didn’t listen to me,” she remembers. But she realized that wasn’t true. You didn’t have to be doggedly committed to your own vision to succeed in this field. You had to submit to the give and take of the process and know how to run with a brilliant idea that comes in the heat of the moment. Howell, who studied French and Art History at Vassar College, began working in fashion in 2004, when she got a job as assistant to the creative director for Kate and Jack Spade in New York. Before that, she had imagined herself working in the art world, but two Kate Spade photo campaigns had seduced her. In one by photographer Tierney Gearon, a child in a devil costume charms and teases his two, well-dressed,unconcerned parents, and another by Larry Sultan features a family that recalls The Royal Tenenbaums . The family members have a taste for minimal art and vintage, mismatched patterns and keep appearing in galleries and patios around New York City. “It was the perfect combo of art and commerce,” says Howell, who wanted to be part of that kind of savvy, sexy visual culture. She would stay at Kate Spade until she left to work at Vogue . First, she was editor-in-chief Anna Winter’s assistant then worked with stylist Phyllis Posnick, a woman known for her narrative approach and the 30 years she spent collaborating with iconic photographer Irving Penn.

“I learned everything from Phyllis,” says Howell, including how to navigate publicists and work with celebrities, skills that would become essential in 2006, when she moved to L.A. to become Vogue’s west coast fashion editor. “Instead of having a lot of designers, the fashion world in L.A. is completely centered around celebrities,” she explains. And while she still does shoots with models, who are used to submitting to visions of stylists and photographers, she probably works with actors more often. “It’s a different hierarchy,” she says, since the actor has as much sway as she and the photographer do, and they have to be involved and well-informed of each decision. “It’s almost like making a mini-movie,” says Howell.

She began freelancing in 2010, and often works with Sebastian Kim, one of her favorite photographers, and the one behind the Elle Fanning and Josh Hutchinson spreads. “The best photographers understand what everyone else does,” she says. She may be talking about Kim, but the same observations could be made of her. “They understand that all the little things affect the picture.”

—

RETURN TO THE HOME PAGE

VISIT CITIZENSOFHUMANITY.COM