HUMANITY: Your new album seems inspired by New York. Are you ever concerned with the idea that people try to regionalize your sound, your music?

ALICIA KEYS: Do you think people still do that? I think music is so homogenized now. But maybe there’s something cool about that. I actually feel like in some ways that’s changed a little bit over the years. There’s something awesome about the ability for everyone to have access to it and also something so cool about the ownership, the culture of it too. But I like that you got that from the music. That’s definitely an energy.

HUMANITY: It sounded very early-’90s New York hip-hop to me. It made me think of Nas’s album Illmatic. That’s what popped into my mind.

AK: That’s one of my favorite albums.

HUMANITY: This may sound funny but that record was sort of dreamy to me—the best word to describe it would almost be “romantic.” Different than most other hip-hop albums, you know? Being from Los Angeles, I think that record made me think, “Oh, New York is cool.”

AK: Yeah, definitely. I love that record. I was in New York, so I can’t imagine what it felt like for people who weren’t in New York, but that’s so cool that it translates regardless. “Romantic” is an ill word. I wouldn’t have thought to put that to it, but it does fit.

HUMANITY: So it’s been about four years since you last put out an album. What’s the inspiration and why so long? Why a hiatus?

AK: I never meant to take a hiatus. It wasn’t the intention. In fact, the music for this album was created so fast—the fastest I’ve ever created music before. It was like raining down every night, like storms of music was just coming out. It was crazy because I never experienced creating like that; I came in already knowing what I wanted to start to talk about. I knew the topics that I wanted to address and I knew who I wanted to assemble to help me create this very powerful sonic and lyrical journey. So everything I did was with so much intention that when the music began it made sense that it just came so fast. We did probably 30 songs in like 10 days.

So I was like this album is going to come out real quick. And then I found out that I was having a baby—my youngest, Genesis—and that put a different time spin on things. And then it became kind of an exercise in patience, and that was really important for me because it allowed me to look at the album—really look at it and live with it and then step away from it, and that was the first time I had ever been able to do that, and it’s really actually empowering because I think for me, I’m pretty much going to venture to say for our society that we’re very fast. Everything is very fast—before we even experience the one thing we’re on to what’s next, and so it was really an incredible exercise for me to be able to have that amount of patience and creating, making sure that everything was in the right space before I was ready to step back into the world.

So it wasn’t intentional and it wasn’t really meant to be a hiatus, but I guess it turned into that a little bit. I imagine a hiatus is when you’re on a beach, and I can’t recall a moment like that. But it’s definitely just the right time now regardless.

HUMANITY: When I was being played the music I was told, “You have to hear these as a body of work.” I thought that was interesting, in contrast to today, where you mostly get singles from artists. It’s kind of refreshing to actually listen to a narrative. As an artist, I’m thinking it’s got to be frustrating if people don’t take it in as it’s intended.

AK: I’ve always wanted people to hear all of my albums. I feel like they deserve to be heard all together, and I think that people actually enjoy that about my music—that they can experience the whole thing and get into it, bringing them into the world. I actually care about creating a body of work that really lives in that way. But I think people find their way to it, and there’s also interesting ways now to do things that allow people to hear it the way it was intended. You’ve just got to think about it a little bit differently.

HUMANITY: When you’re making music, who do you go to for perspective? Who gives you feedback?

AK: I have a tight crew that I go to. In this case there was four of us that wrote the music, and those four people were such an interesting mix—very different than how I normally do. So that kind of brought forth more people into the room than usual. I’m kind of notoriously reclusive when it comes to the creation process. I like to be alone; I like to kind of get my thoughts together. I don’t like to be distracted, I don’t like to have a ton of people around. It just feels like a distraction.

But in this case because it was the four of us all together really creating this music, there would be more people around, and I actually enjoyed it. I enjoyed having them around because it was these very creative beings all together. So it was almost like this electricity. Even just their energy in the room was so kinetic because they were connected to the creative process, and I found that actually allowed me to get a lot more loose and be a lot more in the moment than I have in the past.

There’s an organic thing that happens when you play something for people and they receive it, you feel them receive it. You see it in their face and that is something that spoke in volumes with this album.

And then definitely my husband [rapper and producer Swizz Beats]. I throw things off of him, like, “I don’t know if this is right yet.” He was also one of the four creators of this music. Him, myself, Mark Batson and Harold Lilly. There’s a few other really special groups that came together, but that’s the main group that created the majority of the album.

And then my manager, Erika [Rose], who is a very close friend—she’s somebody who has known me so long, and she’s known me through all of my albums. She just knows my thing. So I’m always listening to her and her feelings. But mostly I like to play it for people who don’t have the connection, because that’s when you get the truth.

HUMANITY: How do you judge success for yourself now?

AK: Success to me mostly is happiness, and when I say happiness I don’t mean that in a generic way. I mean if I’m going through a day and I’m feeling good, I’m feeling that I’m on my path, I’m feeling invigorated, I’m feeling inspired, I’m feeling at the end of the night that it was a good day. To me that’s success, because there is so much in the world that wants to take you out of your happiness, you know, and to figure out a way to maintain that and to maintain inspiration and to maintain excitement, vigor for life and the next thing for yourself—whatever that is, to me that’s success. So happiness to me is success. Honoring myself and honoring my family and making sure that those things feel like they’re in the right order and balance, it can be difficult but it’s possible. But to me, that’s success.

Are you going to bed happy? Are you waking up happy? Because if you’re not then it might be time to change something. I’ve been there plenty of times, and you know what you have to change. You’re like, “This is not good for me,” and then you have to figure out how to unwind it and unravel it and undo it, you know? And it is hard, but you know until you do that you’re not going to be happy.

HUMANITY: Obviously it’s a cliché, but when you become a parent your life just completely changes. I think for me it was the first time I really felt I had a real purpose, you know? Your perspective changes—how you view work, how you view family.

AK: How you view yourself too. I think that was the biggest change for me when I had my first son. I really kind of respected myself for the first time. I know that might sound weird, but I feel like in a lot of ways I did: I respected my time for the first time, and I respected the value of what that meant and what I was giving up when I spent it incorrectly or when I used it correctly. I just knew when to draw the line more, when I didn’t know how to do that before.

I didn’t feel concerned about what I was going to miss out on or what I was going to lose by not doing whatever. Like choosing to be present. That was a big lesson—you grow up. You need to grow up like that.

HUMANITY: When you have someone that you feel responsible for, you have to grow up.

AK: Yeah. And it’s wild. It’s amazing. So good. But it’s true, it’s just crazy. Especially when they first come into the world and you’re like, wow, they’re so delicate, like they need everything. They can’t even move yet. They can’t eat without me. They won’t live without me. Like, if I don’t make sure that they’re good they won’t live. It’s pretty powerful.

HUMANITY: It’s crazy that you can love someone so much that you don’t even really know, you know what I mean?

AK: Right, right. Like, we haven’t really spent any time together.

HUMANITY: They don’t even have a personality but you love them so much, you know?

AK: It’s true. It’s true.

HUMANITY: What’s been your key to a successful relationship, especially in entertainment?

AK: I think the most important thing in any relationship is presence—being present and really choosing to make the time and take the time for the people that you love; not letting everything else be more important, or everyone else be more important, not letting a part of your job be more important or a part of your career be more important, you know?

And communication—really talking about who you are, because we grow, and we should be growing together. There’s no way in the world you’re in a relationship for seven years, 10 years, and you’re going to be the same person you were at the beginning. No way. In fact, that would be horrible. That would be awful, right? So you’re both growing and both evolving and learning more about yourself and learning more about each other, and I think when you give each other the opportunity to continue to know each other, that really strengthens it.

Me and my husband, we have this thing, we’ll call it Keep It Real Tuesdays if it’s Tuesday, if it’s Friday we’re like Keep It Real Fridays, and we just have to be honest, whatever it might be. And I think that’s a really big deal too, because I think you get deep in relationships and you start loving somebody so much, and you don’t want to hurt their feelings, and you know maybe what you’re going to say will be uncomfortable to them so you don’t say it, but you feel it and it’s festering. But whatever it might be, you have to be best friends.

HUMANITY: And you work together—that must add another layer to it as well.

AK: It’s that same thing—as long as we can be truthful. There might be times where I’m like, “I don’t agree with that. I’m not really feeling that,” and he’s like, “You sure? Because I think if we did it this way it could be really good.” And I’m like, “I know what you mean, I just think this,” whatever it might be. I think that’s another thing that happens in relationships; suddenly you can’t have your own opinions anymore. You do have to be an individual as well.

HUMANITY: What have been the lessons of motherhood thus far?

AK: The lessons of motherhood? Damn. This is serious. In what capacity?

HUMANITY: What have your kids taught you? What have you learned from your children?

AK: A lot. The great stuff, like the wonderment of it all, remaining in wonder of the world and of life. My youngest is learning all these words now. So everything is “Hot tea. Tree.” All these simple things, and I’m like, “Yeah, that’s hot tea. Yeah, that’s a tree. Yeah, that’s a sock. Yeah, that’s a shoe.” It seems so mundane and simple and silly, but when he looks out and says “tree,” it is so beautiful. Like, look at that tree. That tree is in the ground and it grew, and it’s tall and it’s huge—how did that happen? All the elements of the earth came together and made this tree. So to not forget to be in wonder of all the things around you, as simple as they might be. Not taking them for granted. It’s so special, you know?

Another big lesson I’ve learned, and it’s a hard one—as a parent, I’m still figuring it out; I can’t say I’ve mastered it or anything but letting go, letting your kids have their own path. They are going to discover and they have their own journey, their own way they’re going to figure out how to express themselves in the world and who they’re going to be, and I think a lot of times as parents we project our thoughts or fears or images on them, and we have to let them be a little bit. We can’t always answer every question; you don’t have to tell them how to do it. They can figure it out, and we should give them the space to figure it out.

So what it’s taught me is to not be so quick to tell them what to do or how to do it or what’s the right way or what’s the wrong or what’s good or what’s bad. Let them figure it out, because they will, but it’s hard. You want to protect them, but sometimes you protect them more by allowing them to learn for themselves.

HUMANITY: You’re both very successful. Are you ever concerned that the two of you could overshadow them as they get older?

AK: I have thought about that before and I have met children of successful parents and it goes many different ways. Some are really interesting, go-getters and forward thinkers, and some are really almost nervous and shy and almost crippled. Maybe they haven’t felt the presence of their parents or the stability and that’s crippling in its own way as well.

But I think as long as we are giving them the proper guidelines and teaching them how to put in the work—because it won’t matter what I do, it won’t be real if they don’t put in the work and to me that’s important. You can’t be afraid of work.

HUMANITY: But at the end of the day your kids are going to grow up with a completely different reality than you did.

AK: True. True.

HUMANITY: So as a parent, how do you keep them grounded when they have so much access?

AK: I’m big on limitations. I’m all about earning it. He actually has a point system that he has to earn in order to do certain things. So I think earning is very important.

The value of a dollar is very important and that’s something that we talk about now. He has what he saves and what he’s going to spend and what he gives away.

Surely it’s going to be different for them. But if we go to the toy store, he can’t just get everything that he wants. “What one thing would you like today?” And he answers, “I want that one and that one and that one.” “But you got to pick one. What are you going to pick?”

So just limitations, and we talk a lot about what other people might need and how he could be helpful to that. Every year on his birthday it’s time for him to look at the toys he has and figure out what is he ready to give away to somebody else. Just consciousness about how it all flows. We all have to give to receive and receive to give, you know?

HUMANITY: It’s refreshing to see somebody lending themselves to something bigger than themselves. Can you tell me about your work as a founder of Keep a Child Alive and the We Are Here movement?

AK: I got involved about 15 or 16 years ago. It was the very first thing I ever got involved in, and I’m so blessed to be able to learn that so young. Keep a Child Alive provides medicine for children and families who have AIDS who can’t afford it. We also provide surrounding care around that as well. There are just not a lot of places you can go and get treated or get tested or get food even, and you can’t take AIDS medicine and not have eaten. It’s important; at this point we’ve helped almost 2.5 million people.

With the We Are Here movement I was just personally angry—angered by turning on the TV and every second seeing this constant disrespect or inequality, and that’s really what the main focus of We Are Here is about; it’s really about inequality and justice all over the world. So We Are Here focuses on different organizations that focus on issues that I believe, when we look at them all together, will really be part of what will change the world for the better in so many ways.

We care about gun violence, about justice reform, children in war-torn environments, poverty and hunger; we care about women’s empowerment and equal pay. We’re in 2016 and we’re still talking about inequality of women in the workforce. Give me a break.

HUMANITY: Your “Hallelujah” video is obviously a look at the refugee situation, forcing us to think about it as if it was affecting us personally. Oftentimes we here in the States think it’s not here so it doesn’t affect us, so when you put it in that context you have to think of it as just a mother and a child who are going through this together, and that’s the takeaway.

AK: That was exactly the point of doing this video—to set it right in our backyard. It’s just so important how we’re dealing with the immigrant issue here in this country and just to think about if this was happening to us—would people on our borders be willing to open their borders to us?

They should; we all should. It should not be this way where we’re treating people as if they don’t belong or we can’t figure out how to help them, while they are suffering and going through this drastic, horrid circumstance. We have to look at each other with more compassion. It’s kind of turning us into monsters. It’s pretty scary. This election year is definitely displaying that mentality. It’s just so important that we are not turning into monsters.

HUMANITY: Your place in music history is cemented. But what’s important to you? How do you want to be defined? What’s the legacy that you want to leave—how do you want people to see you beyond just a musician?

AK: I definitely want to be remembered as one of the greatest artists of all time that created timeless music that will live forever; like, how I feel about some of the great artists that inspired me, I definitely want that.

But I also want to be known as somebody who really was a part of change, you know? Some of the greatest artists that I have admired really spoke out about issues and things that they believed in and what was wrong in the world, and I want to be remembered for that.

One of the things we’re working really hard on now is justice reform, because there is so much that has to be changed about our justice system. It’s broken. Young people are being locked away for their entire lives for a nonviolent crime. We have to think about how we can treat people and how we can actually rehabilitate people as opposed to just locking them away and throwing away the key. It’s a very old concept.

I want to be able to have the ability along with all of us together to change those policies and to hopefully have a voice to say look at what’s going on. I think that’s why I have been given this opportunity to speak and to sing and to relate to people; it’s so that we can also change shit. It doesn’t have to be the same forever.

HUMANITY: Who are some of your heroes?

AK: My mother. She’s obviously a personal hero. She’s definitely a very powerful woman to me who has taught me so much.

My partner in the We Are Here movement, Leigh Blake, she’s the one that decided to open my eyes to activism and to be an active citizen, not just standing back but being bold and brave and swaggity and fly about it, you know? So I really admire her very, very much.

Maya Angelou is a personal hero for me—those beautiful words and those poems, and that way to look at life in triumph is really powerful to me.

HUMANITY: Last question: What’s something that maybe people don’t know about you that you’d like them to know?

AK: They’re going to find out. They’re going to find out right now.

HUMANITY: That works. Thank you very much. Unless there’s anything else you want to cover?

AK: I think that’s everything. Well, maybe just one other thing I’ve learned more recently is how to be fully yourself and how to just be at peace with imperfection, and really letting go of that. Because I think that the more I live, the more I see. We get very caught up trying to please everybody else and trying to look like everybody else and be like everybody else. And I just personally am in a comfortable place where I really don’t want to do that anymore. I feel so different than I’ve ever felt before.

HUMANITY: It’s funny you say that because my perspective on you was different before meeting you and hearing this last record. I think before I saw this artist on a stage, and this record, it just feels so relatable.

AK: Yes, yes. And that’s because I’ve finally let down the curtain. I’ve let go. I didn’t mean to be that way before; I definitely didn’t mean to do it.

HUMANITY: It’s funny, to me in the ’60s and ’70s it almost seemed like artists were the peers, the voice of that generation, and I don’t know if it was MTV, but at some point it just kind of disconnected, you know?

AK: That’s how I want to be remembered, as the voice of a generation. Thank you, sir. That was what I was looking for.

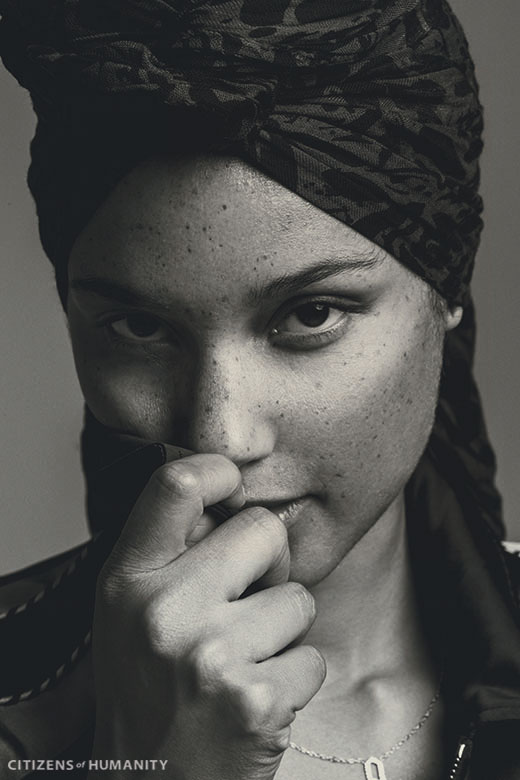

Fashion Credits:

Look 1 – Xuly Bet Black Bodysuit

Look 2-4 – Louis Vuitton Silk Bomber Embroidered Jacket, Dries Van Noten Silk Bra

Look 5 – The Estate of Jean Michel Basquiat Cotton Scarf, Denim Jacket and Customized T-Shirt by Citizens of Humanity

—

RETURN TO THE HOME PAGE

VISIT CITIZENSOFHUMANITY.COM