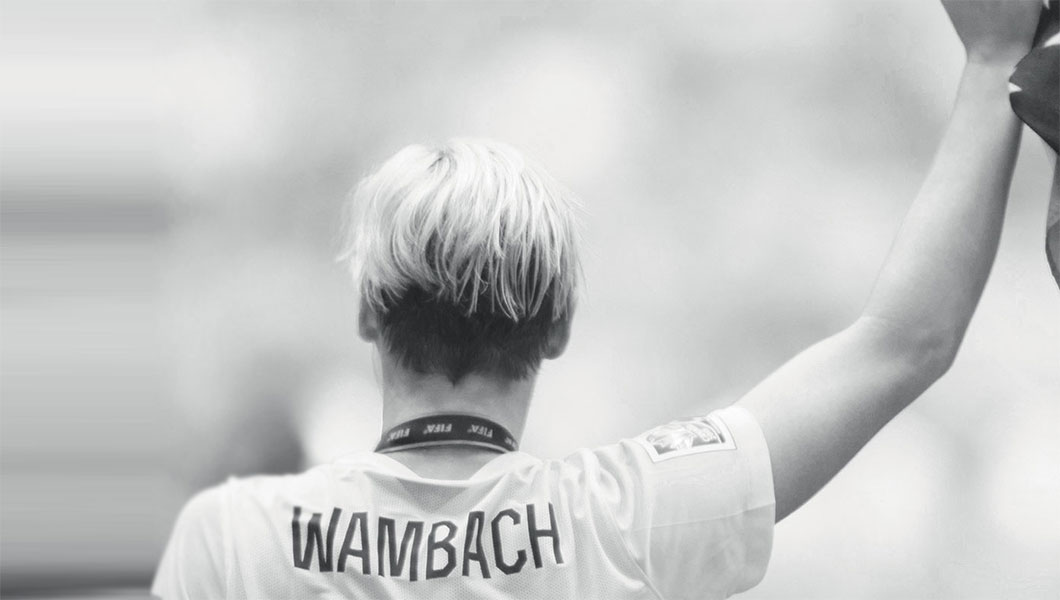

Abby Wambach played her final game with the U.S. women’s national soccer team on December 16, 2015. It was blustery in New Orleans that day, though she and her teammates were sheltered inside the city’s Superdome. By this point, after 14 years with the team, she’d scored more goals than any other soccer player in international history, male or female. The U.S. team hadn’t lost a game on home soil in over a decade. For Wambach’s last hurrah, they assumed they’d win again, against China’s national team. Insatiable scorer that she is, Wambach tried a few times to connect ball with net. But it was China’s Wang Shuang who scored the game’s single goal.

The loss seemed almost fitting, however. Wambach has two Olympic gold medals and a World Cup championship to her name, but she has long treated failure as fuel. She still talks about an anguished loss at a high school championship as if it opened her up to her future. “I’ve been trying to prove myself ever since,” she told USA Today a few years ago. “There’s going to be things that go wrong. It’s always about how you handle them.”

After the game with China, Wambach returned to the field, microphone in hand, to address a crowd that included eager young girls with glittery signs that said things like “Thank You Abby” or “My Hero.” She fought back tears as she spoke, in her typically candid way, before dropping the mic on the AstroTurf and turning into the arms of her teammates.

No one would have faulted Wambach for disappearing from the public eye after that. She’d been playing professionally for 15 years and deserved some time to regroup. But in the months since winning the World Cup in summer 2015, she has been taking every chance to speak out about gender disparities, finding her voice as if spurred on by newly discovered fervor.

“Mostly, I’m angry at myself,” Wambach explains, talking by phone from her home in Portland, Oregon. She has just returned from speaking about income inequality at the U.N. headquarters in New York. Soon, she’ll be lecturing at a number of universities, as part of a speaking tour that came together almost organically. “When you’re inside of something, you don’t see what it’s like until you’re outside of it …”

When she started planning her retirement, she realized she would have to create her own 401K and probably launch a second career to support her family. Male players, even those with résumés that pale in comparison, face no such concerns.

“These guys make hand over fist what we make,” she says. “I think I was trying to fool myself into thinking I wasn’t being mistreated. I should have spoken up. Maybe I was scared. Since retiring, I don’t have that fear.

Wambach, born in 1980, is the youngest of seven siblings and grew up in what she calls a “team environment.” As a 5-year-old, she scored 27 goals in three consecutive games. Her mom put her on an all-boys team when she was 9, to challenge her. Wambach’s coach at the University of Florida, Gainesville, Becky Burleigh, would boast that Wambach didn’t play like a girl, knowing even as she said it that it was both a compliment and a quandary—a reminder of how stigmatized “playing like a girl” still was.

Wambach joined the U.S. women’s team in 2001, the year she turned 21. Her glory moments abound: the time she headed a ball into the net to beat Brazil during the 2011 World Cup; the time she had a gash across her forehead stapled shut fieldside so she could keep playing. But in the lead-up to the 2015 World Cup, she wanted to transition into a supporting role, let her younger teammates take the limelight. She’d just married her partner, Sarah Huffman, and had started thinking about her future. She knew 2015 would probably be her last season. “I wanted to completely accept a selfless role,” she says. “It seems frivolous to do things like pick up cones, but in life these small little things matter.”

Almost paradoxically, Wambach’s candor doubles as a form of modesty—a commitment to honesty over showmanship. Even when she says she wants to change the world, it’s as if she’s saying it because it’s the obvious task: “All of us—women, men, transgendered people—we have certain proscribed paths, social pressures.” If no one talks about the inequality such paths and pressures breed, nothing changes.

On April 2, 2016, Wambach was arrested for driving under the influence while heading home from a dinner in Portland—an unexpected interruption to the momentum she had been building since her retirement. She posted on Facebook the next day: “Those that know me, know that I have always demanded excellence from myself. I have let myself and others down. […] This is all on me.”

The post racked up 7,500 comments, some saying how they respected her accountability, some telling stories of their own encounters with drunk driving or drunk drivers. One high school student commented, “You made a mistake. That will not change how I or my teammates look up to you.” The overwhelming message was one of support: Nobody thought she was perfect; she is a hero nonetheless.

Three weeks after her arrest, Wambach headed to Silicon Valley to give a keynote lecture on workplace equality at the Watermark Conference for Women. “I want to be the same person in whatever room I’m in,” she says on the phone, explaining that she didn’t really have to adjust her approach when addressing policymakers and business people. “It’s not really that hard to be authentic. You say what you mean, and go after what you want.”

—