WHAT DO BOB MARLEY, PAUL MCCARTNEY AND THE CLASH HAVE IN COMMON? THE ANSWER IS LEE “SCRATCH” PERRY.

I first unknowingly encountered the musical genius of Lee Perry on my first trip to Kingston early in 1973. In Jamaica music was everywhere—blaring from innumerable tiny record shops out into the streets, from car radios stopped at red lights, from small transistors of commuters waiting at bus stops or people just randomly singing a cappella as they walked through the city’s hot bustle. At night there were sound systems anchoring giant outdoor mobile dances going into the wee hours—celebrations resounding without borders. Bob [Marley] was my guide through this mystical musical universe so intrinsically bound to a struggle for freedom—political, economic and spiritual.

In Jamaica more records were being released per capita than in any place in the world, and “dub” music was dominating. I was amazed that radio play and the dance halls—pushed by popular demand—had made stars of people who simply talked over rhythm tracks. They were liberating poetry from the printed page and simultaneously chatting over music that was as sophisticated and innovative in its use of electronic effects as any being produced by European or North American composers, such as Karlheinz Stockhausen or Terry Riley—but with the distinction that this music was penetrating the popular consciousness.

My first weeks in Jamaica I was trying to absorb as much as I could. Bob and his partners in the Wailers—Peter Tosh and Bunny Livingston—were introducing me to the ways of Rasta culture, and I was becoming aware of the names of some of the artists dominating the airwaves: Big Youth, U-Roy, Dennis Alcapone, Alton Ellis, Prince Jazzbo.

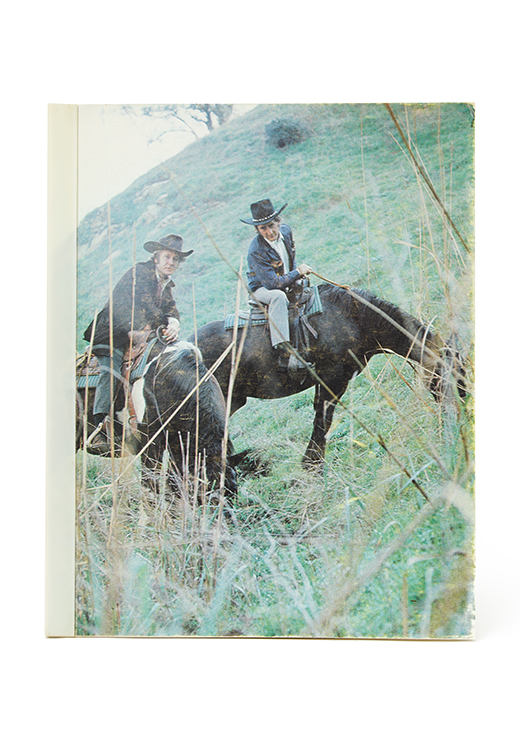

I would ride with Bob every sunrise in his bronze Mercury Capri to run on the beach at Bull Bay, 20 minutes from Kingston, where Bunny lived among a small Rasta community. Then we would run up a nearby mountain to a canyon holding a 50-foot waterfall at Cane River. In the afternoon nearly every day I would go with Bob to West Kingston, where poor people—the “suffaras”—lived and where Bob grew up, and to Trenchtown, where the Wailers were formed.

I would goad Bob into taking me on trips to the interior of the island, its mountainous beauty a striking dichotomy with the slums of Trenchtown, Back-o-Wall, Firehouse and Concrete Jungle. It seemed incredible to me how all the country people knew him like a son or brother or nephew, and I could never tell for Bob’s actions if they really knew him or were related or just loved him for the joy and hope his music would always bring. We stopped on these small winding country roads in the mountains of St. Ann’s Parish on my first trips to Nine Mile, the tiny village where Bob was born. And I loved to stop at the little roadside shops of zinc and wood, because there would often be an ancient jukebox where I’d look for Wailers music and so began discovering their early ska songs like “Simmer Down,” “Caution” and “Let Him Go.”

I can remember so distinctly hearing the quite different sound of Lee “Scratch” Perry’s Wailers productions for the first time at one of those tiny shacks. It was a lazy golden afternoon; we had stopped to drink a jelly coconut and Bob went around back to check if there was a good draw of herb. Handwritten on one of the jukebox selections in fading ink was the title of one of their collaborations, “Duppy Conqueror.” What a wild name for a tune! It’s Jamaican patois for “ghostbuster.” I loved the way Bob’s voice was recorded as he sang:

Yes, me friend, me friend / Dem set me free again / Yes, me friend, me good friend / We deh ‘pon street again / The bars could not hold me / Force could not control me …

It sounded so solitary—desperate and piercing yet smooth raw honey all at once, with pristine background vocals, original harmonies and a rhythm section that locked the spaces between the bass notes sweet as a ripe mango. The flip sides of the 7” vinyl were vocal-stripped rhythm tracks brilliantly reconstructed, the various overlapping echoes reverberating again through the lush green otherworldly Jamaican mountains.

Our leisurely drive to Bob’s village became a journey into the man’s artistry for me. The afternoon was wearing down to a soft dusk as Bob and I made our last stop before reaching his childhood home. I walked into the shady bar and found myself at the jukebox, pressing the fat square button to hear “Trenchtown Rock.” Losing myself in the song, I understood Bob’s radical affirmation of his impoverished Kingston area as a place of resilient citizens always ready to dance in the face of pain. Its opening line is etched permanently in my being:

One good thing about music, when it hits you fell no pain / So hit me with music, hit me with music now … / Trench town rock, big fish or sprat / Trench town rock, you reap what you sow / Trench town rock, and everyone know now / Trench town rock, give the slum a try … / You’re groovin’, in Kingston 12 …

No recording had ever awakened me quite like that. I was so blown away, and I needed to hear the scratchy vinyl through the ancient machine again and again. It was one of their first discs after leaving Scratch’s stewardship, and they had learned his lessons well.

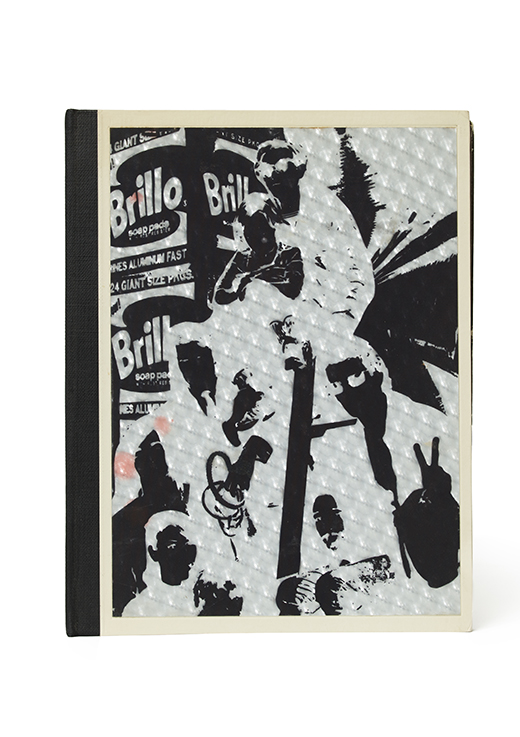

To say that Lee Perry is a living legend is surely out of the realm of hyperbole. As one of the most influential producers in the history of recorded music his importance is reflected not only in the hundreds of millions that have been touched by the music he has created—as a producer, writer, vocalist and live performer—but also by the incredible range of artists who have been profoundly inspired by his body of work extending through five decades. Beginning in the early ’60s he collaborated with legendary Jamaican artists of the ska and rocksteady era, including the Skatalites, Alton Ellis, Tommy McCook and Prince Buster. In the late ’60s and early ’70s he was a foundational creator of reggae and was a profound influence on the careers of the Wailers. He took what was then a vocal trio (Marley, Tosh and Livingston) and brought them together with his studio rhythm section, known as the Upsetters, and in so doing lifted them out of the age of ska and rocksteady and into the realm of a new music whose profound global impact continues to this day. He produced hits with dozens of singers, including seminal tracks like “One Step Forward” with Max Romeo, “Cherry Oh Baby” with Eric Donaldson (later covered by UB40) and “Police and Thieves” with Junior Murvin. He is one of the inventors of dub, which combined radical experiments in electronic music (panoramic delay, extensive use of echo and inventive collaging techniques), deconstructing and reconstructing current popular recordings, and produced in 1973 Blackboard Jungle Dub, the first purely dub album. His dub experiments coincided with his work with toasters U-Roy, Prince Jazzbo, Big Youth and others, creating some of the first recordings of people talking on top of music and foreshadowing the birth of rap and hip-hop in New York nearly a decade later.

As his legend grew, artists outside of Jamaica gravitated to him, looking to share in his magical gifts. The list of artists who have worked with him crosses genres and geographical boundaries, everyone from George Clinton and Keith Richards to the Slits, the Orb, Dub Syndicate, Bill Laswell and more recently Dubblestandart and Subatomic Sound System. Scratch produced the Clash’s “Complete Control,” widely acknowledged as one of punk rock’s greatest singles, a fiery diatribe against corporate control of the music business. As an artist, Rolling Stone has rated him among one of the 100 Greatest Artists of All Time.

Scratch’s bold personality and talent is well documented. The genre he helped to invent, dub, has gone on to rule dance floors everywhere, filtered through sounds like grime and EDM. But for me, his greatest triumph will always be the sonic kick of hearing Bob Marley’s voice of liberation on “Duppy Conqueror,” proudly riding a radical rhythm that could only have been made by “the Upsetter,” Lee “Scratch” Perry.

—