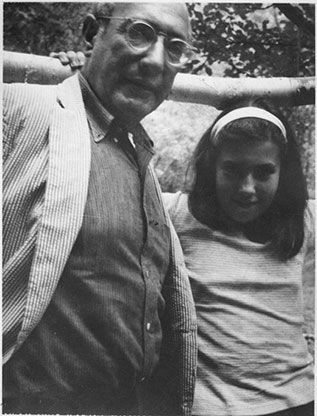

MANY PEOPLE HAVE PRECONCEIVED NOTIONS REGARDING AN ARTIST’S CHARACTER. THE ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISTS WERE KNOWN AS STORMY, MOODY INDIVIDUALS, WITH PAINTER MARK ROTHKO DEPICTED AS ESPECIALLY DARK AND ANGRY. BUT THERE WERE MANY SIDES TO ROTHKO, SAYS ONE PERSON WHO KNEW HIM BETTER THAN MOST.

“When I’ve seen my father portrayed, I’ve sort of winced, because it doesn’t sound like him or come across like him,” says Rothko’s daughter, Kate, now a retired pathologist. The Mark Rothko she knew painted masterpieces, but also hung holiday ornaments and was a jovial storyteller nicknamed Bunchie by his wife. “He was a very warm, humorous person,” she says. “I remember him telling me silly stories as a child. He was a laughing, joking person, so when I’ve seen him portrayed as this tyrannical screamer, it’s been very difficult. He was also a normal father.”

Kate grew up surrounded by her father’s works, densely hued floating rectangles or “color fields” that are iconic in the canon of abstract expressionism, the first American fine-art movement. Aged 19, Kate embarked on a landmark legal case known as “The Matter of Rothko,” in which she ultimately saved more than 700 of Rothko’s paintings from being stolen by his gallery, aided and abetted by the executors of his will—people he thought were his best friends. Relying on an iron will no doubt inherited from her father, Kate demonstrated that justice can prevail, even in the most impenetrable circles of the art world. Today we are able to see this treasured artist’s works, works that would have disappeared altogether from the public view, thanks to her.

Kate Rothko Prizel was born in New York in 1950 to Mark Rothko, a Jewish immigrant from the Russian empire, and his second wife, Mary Alice Beistle, an American illustrator known to everyone simply as Mell. Each night, Rothko would come home from his art studio and tap “hello” on the basement kitchen window. “We had a brownstone at that point, so the kitchen was one of those where you would have to go down a few steps below the street level. My mother was usually down there preparing dinner and I might be helping her when he came home and knocked on the door.” Whenever Rothko was home, you could guarantee there would be classical music playing on the phonograph. “Mozart, all kinds of Mozart, from opera to chamber music to symphonic music,” she says. “He also fairly successfully taught himself to play a Mozart piano sonata, sitting at an upright piano on our lower floor, which I was very impressed by.”

Rothko was at his studio six days a week, but on Sundays his job was to take Kate to Central Park. She remembers her father teaching her to ride a bicycle, even though he could not ride himself. “His idea of teaching me to ride a bike was basically to run behind the bike and scream, ‘Don’t fall!’ ” The family celebrated both Hanukkah and Christmas, and Kate remembers one year her father said he didn’t like that the Christmas tree balls dangled down from the tree; “He thought it was not cheerful,” she says. “So he took them all off the strings and attached them directly to the branches, sticking out.” One of the few times Kate remembers hearing her father curse was when he struggled to position the star on top of the 12-foot tree.

The family home was eclectic and unusual, filled with a combination of her father’s paintings and repurposed furnishings, often picked up at the Salvation Army or in Cape Cod, where the family vacationed for several summers. They never installed any formal lighting for Rothko’s pictures. “We simply had white walls and white ceilings, and projected light off the ceiling to light the paintings,” she says. “Now, in museums, you have to stand a few feet away from the art, but in our house you were living with the art, and there didn’t seem to be any worry about it. It was just part of the whole atmosphere.”

Her first memory of a specific painting is of Homage to Matisse, one early work Rothko painted in his mature style. “I was 4 or so, and I know we had other paintings hanging in that apartment as well, but that’s the one that stood out to me so vividly. It was very important to my father because he worshipped Matisse. It’s so distinct among my father’s paintings that it stuck with me my entire life.” Her father’s workaholism was well known, but Kate did not feel neglected, or in competition with art for Rothko’s attention. Rather, she loved the art and was intoxicated by it. “To me, there was nothing in the world greater than to be an artist,” she says. “I grew up thinking the art world was the most idealistic, magical world. I didn’t think any other world could compare.”

Rothko painted alone, but often, Mell would drop Kate off at his studio for the day. Rothko would sit Kate in her own corner with some paints and paper and face her away from him. “I think he hoped that I would entertain myself so that he could really paint in peace and quiet without feeling like he was being watched.” She did sometimes observe him, though, from the corner of her eye. “I certainly have images at the back of my mind from visits to various studios when he was working on different projects,” she says. On her 12th birthday, Rothko gifted her one of those paintings, a study in orange and reds, inscribed to her.

When she was 16, Kate and Rothko took a cross-country train trip together. It was 1967 and Rothko was teaching a class at Berkeley. He refused to fly, so Mell flew with Kate’s younger brother, Christopher, and Kate traveled by land with her father. “It is now the trip where I look back and wish I had talked to him about his philosophy of art, about his family history, all sorts of things … but we both just spent a lot of the trip in kind of awkward silence.” She’ll never forget sitting next to Rothko watching the sun set as the train crossed the great Salt Lake in Utah in a miraculous explosion of red, amber and violet.

A year later, in the spring of 1968, after completing a series of 14 huge, monumental paintings for the Rothko Chapel in Houston, Rothko suffered a mild aortic aneurysm, with devastating after-effects on his body and mind. Rothko became depressed and difficult to communicate with. And for six months, under doctor’s orders, he painted on a small scale, until he couldn’t bear it any longer and returned to his large-form paintings, creating a series of foreboding black-on-gray canvases. “It was very hard for me to separate the increasing darkness of his paintings from his mood,” says Kate. “It took me quite a number of years after his death to understand that those dark pictures were really about him taking his work in a new and, if you will, higher direction, rather than being a reflection of something personal in his life. I think this is perhaps the greatest evolution in my feeling about his work.”

In November 1977, seven years after her father died, Kate would win the battle to reclaim the work. But 97 paintings were never returned—including Homage to Matisse— these works still remain in private hands to this day. For years, the only thing she hung on the wall at home were two museum posters. “We were still students and weren’t in a place where we could have hung a Rothko,” she says. It wasn’t until she and Ilya (her husband and then boyfriend) bought a house and began raising a family of their own that they decided they were ready to hang the work at home. “I like living with them more than anything,” she says, and watching her own children and grandchildren light up in the presence of her father’s paintings has been especially gratifying. “Because that’s the way I grew up too … with them around me.”

—