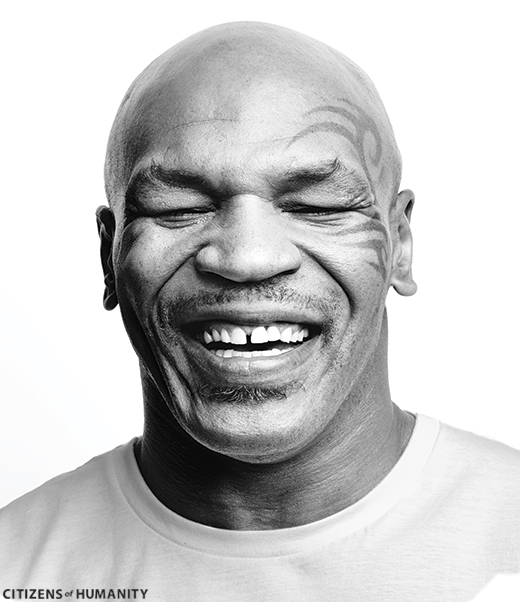

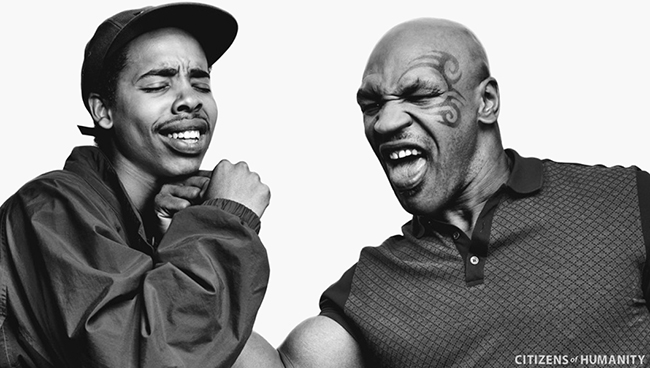

At the start of each issue, we all sit down to brainstorm potential profiles and features; Mike Tyson has been on this list since issue one. With the article now realized, the ideas that everything happens at the right time for good reason and nothing great comes easily ring all too true. When the opportunity to do a feature on him became a real possibility for this issue, the question internally became how to share a side of Mike Tyson that is different from the countless interviews, articles, biographies both authorized and unauthorized, documentaries and films to date.

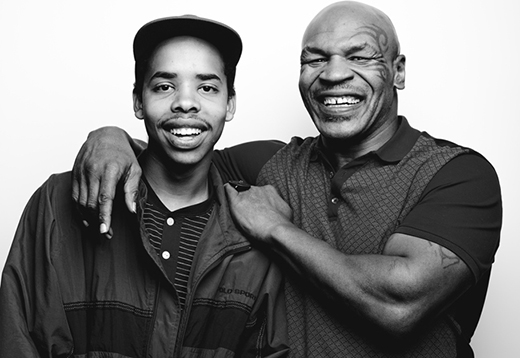

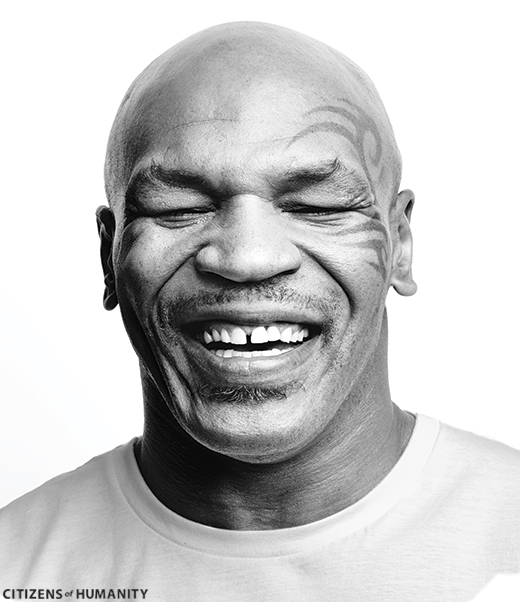

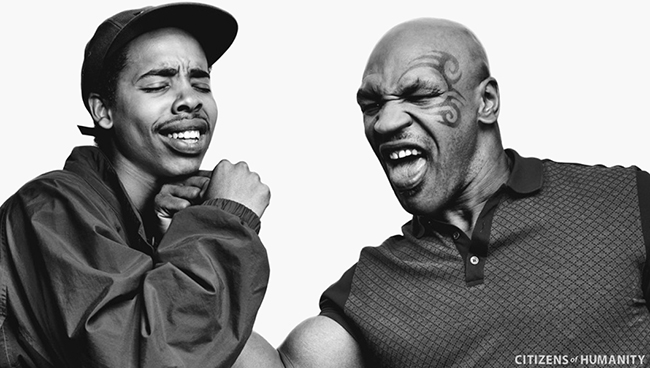

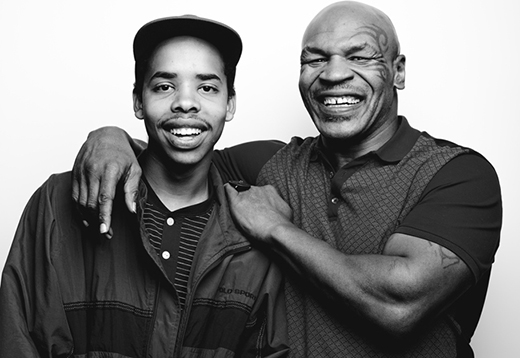

We all agreed that our best shot at having a unique angle would be to find the right person to interview him, and thanks to Leila Steinberg, Earl Sweatshirt of Odd Future agreed to the task. On November 4th, we took a flight to Las Vegas, where Earl sat down with Mike. There were many times when this interview could have fallen apart, both in the days and weeks leading up to it and even after we arrived, but it happened, and the results were worth every moment. I didn’t know much about Mike Tyson prior to this experience, but what I learned from him is invaluable. That is not to say he is without faults like all of us, but he’s the first to admit them, and his honesty, openness, insight, strength and perseverance make him someone I greatly admire. I hope you find the following conversation as rewarding as Earl and all of us at HUMANITY do.

Mike: How old are you, man?

Earl: I’m 20.

Mike: What do you have to say to me?

Earl: So I got presented with the opportunity to come talk to you.

Mike: Yeah. Where are you from?

Earl: I’m from LA. So I was trying to figure out kind of what angle to start at when I first got approached with this.

Mike: Are you now?

Earl: Well the first thing that came to mind after doing just a little bit of research that I did was just some of the parallels that – just between me and you, that I thought we had just at 20. Just with being in the position that you was in.

Mike: I mean, you’re pretty much an idiot at 20.

Earl: Right, that’s what I feel like. I got to 20, and I –

Mike: You’re not an idiot, but you are. You don’t really think you’re an idiot, but you are.

Earl: Right.

Mike: But you don’t think it. Like you’re in agreement, but you’re an idiot.

Earl: No, I swear, I was talking to someone yesterday, and I said the mark of me being an adult was when I got to the point where I realized how little I knew.

Mike: Oh, man. I’m humbled with that every moment of my life. I think I know a lot, but I don’t know anything. I think I know a lot; they talk about a lot of subjects and issues but in the scheme of the world, it’s really not even a grain of salt.

Earl: So, I just thought you would have some real valuable insight just to give to people who are in positions like mine or just similar to mine where you’re just a young person getting pulled from every single different direction.

Mike: Who’s pulling you? Record companies and stuff?

Earl: Well, at first it was record companies, and then when that kind of settled down, it was management.

Mike: What do you need management for? When you think about it, what’s the purpose of management? In boxing, in my opinion. For boxers! I think they, I don’t know, they’re glamorized babysitters.

Earl: Yes, 100%.

Mike: So they say, “Hey, come here. We gotta go here. We gotta go there. We gotta go here. We gotta go there.” You have to give 10 or 15% of your money, whatever it is…

Earl: To think for you, almost, to handle like, kind of mindless duties.

Mike: Yeah, you’ve thought about that too?

Earl: Yeah. Me and Leila always talk about that, she tells me all the time I am unmanageable. Just because I am reclusive and I am the worst at communicating.

Mike: Well, that could be good too. Because the most important thing in the world for show business, really, you know everything’s a high-tech business, but what people want now is what they can’t get – exclusivity. You know, when you’re exclusive, you know what I mean.

Earl: It’s the allure.

Mike: Yeah.

Earl: It’s what draws people to you.

Mike: None of us are really who we appear to be. Like me talking to you, this is not who I am.

Earl: Right.

Mike: We’re in an interview. This is not who you are. We are never who we appear to be.

Earl: Mhmm.

Mike: And yeah, but like you said it’s the allure, exclusivity. The less you give, the more they want.

Earl: It’s what has worked with so many people. I don’t know if you know one of my favorite artists, André 3000, like he has dropped probably 10 or 15 songs that fans of his know every single word to, as opposed to like 1,000 songs, some is good, some is bad. A testament to the exclusivity.

Mike: Yeah, he is a big-time guy.

Earl: Because he does so little.

Mike: Sometimes, people have reasons for being that way, something that you’re hiding, sometimes just like – some people don’t want people to know them, because they’re vulnerable. They have no more power, they feel.

Earl: That’s true. I think mine was more gradual, because I used to be a much more social person. And when I was 16, I got sent away for bad behavior by my mom.

Mike: What did you do?

Earl: I hadn’t done anything specifically, but it was just like –

Mike: Did you break the law?

Earl: I broke the law, but it wasn’t so much that, she was worried about my identity, you know what I mean, and just how I was establishing it. Like the man I was becoming. So I had to spend that year and a half just like searching for myself, you know what I mean, just like figuring myself out.

Mike: We don’t know at 20 years old the man we want to be. I just recently found out the man I wanted to be in life. I said, “This is the guy I want to be.” And I realized everything I did in the past prevented me from being the person that I wanted to be, so I don’t do what I did in the past anymore. But it took me to be what, 45, 47, 48 to really get it, so it’s not like I’m some genius. I learned from experience, no one told me to follow anybody else’s example, I had to feel the stove to realize it was hot. Some people say I’m an idiot because it took me this long to get it and some people can get it right away, some people take a long time. But I got it, At least I got it, some people never get it. I grasped it. I realized I’m not in the streets, I’m not in the clubs no more, you know, I’m not sleeping with strippers or anybody like that.

Earl: Right.

Mike: But whatever it is I’m just not doing that. I never really knew what dignity was until recently. And I realized that more so not because of myself but the response I get from people, you know, a woman won’t have to worry about talking to me and worrying about me hitting on them anymore or anything like that.

Earl: And that’s gotta be the best feeling.

Mike: Yeah, it makes me feel good, because when you sleep with so many people, all my life I thought that was adding to who I was, but it takes so much away from you.

Mike: You know anger is my biggest enemy in life. I do a lot of reading on the history. I read the history, the whole history of the world, you know, from the beginning. And we have so many people, a lot of people. But do you know what we did more than fornicate?

Earl: Fight?

Mike: War, yeah. We fought more than we fucked. Ain’t that crazy? We got billions people on the planet. Even from the beginning, from the beginning of time when that book starts, fighting! What are we getting into now? Fighting! Fighting…from all that fighting, great names, great great great names, them fools be fighting, you know like George Washington All the great names, all these names came from fighting. And what for…

Earl: Fighting against something.

Mike: Yeah, themselves.

Earl: Some were fighting for like civil rights, you know – like it’s all fighting.

Mike: I think war is led by faith. I never think of physical fighting. It’s always spiritual. Fighting is spiritual.

Earl: Absolutely. Yeah. I got familiar with that concept early, just because my mom, she was always working, so she dropped me off at this martial arts dojo. And the dude instilled – we had to meditate for an hour every time, before we did anything. We would meditate. Just to connect to the spiritual side of it. And like, going inside of yourself and realizing the immense power that lies within you, just as a person.

Mike: You know young man; it’s all about spiritual awakenings. I could never stop drugs, I could never stop drinking, doing stuff, until I received my spiritual awakening. Now it’s not a problem anymore. But I’ve been doing this since the ’90s, late ’90s and I never could stop but I never understood the spiritual awakening. And once that comes into play, it’s really eye opening.

Earl: It’s so much bigger than human constraints.

Mike: You’ve got brothers and sisters?

Earl: yeah, I do. Like, my friends are my brothers. Like my real close ones. I got them like that. And I got siblings on my father’s side.

Mike: Tell me about you man, who you are, what’s your shtick, man.

Earl: I do music. So I came –

Mike: Like songs and stuff, records and radio and stuff?

Earl: Not so much radio. I was fortunate enough to – we like developed our own, like self-sustaining like fan base that was separate. So when I was like 14, I was getting better at rapping, like running around L.A., trying to find like people to do music with. And I linked up with this dude Tyler. And he had this whole thing going on already. We started making music, and it was like, it was idiot music, but it was really, I think, what we had in hindsight, what attracted so many people to it was potential. Like we weren’t necessarily talking about anything, but the way that the music was, it was like sophisticated in a sense for our age. So anyways, we’re doing that.

Mike: What’s the name of your music?

Earl: The group that I was in was called Odd Future. So we was doing that. Fast forward, 2010, so I want to say that was like 2008 to 2010. Mid 2010, I got sent away. And we blew up. Like at that moment, it was like hand in hand. I got sent away, and –

Mike: Tell me what you mean by “blow up”. I know what blowing up means but how did you experience—define “blowing up”. You got signed? They played your music?

Earl: Yeah, they started… but it wasn’t even so much, that they played our music on the radio, it was –

Mike: Clubs?

Earl: It was like – it was almost punk rock in the way that it took off. It was just kids became, like, obsessed with it, because they –

Mike: You a crunk dancer?

Earl: Nah…We didn’t dance too much, but it was – they got attached, because in the same way that that punk expressed, like, the angst of being a teenager so well, a lot of our music and early energy had a lot of those elements. You know, that teens, really attach to, you know what I mean – just illogical… passionate unaimed anger, you know. Like, I don’t even know, but I’m just swinging.

Mike: When’s your birthday?

Earl: February 24th.

Mike: Is that Pisces?

Earl: Yes, sir. So I get plucked out. It blows up while I’m gone. The whole time that I was gone, for the first year, I went to hell. It was the worst. Because I wasn’t involved.

Mike: Well, how exactly you wasn’t involved, because you weren’t there physically?

Earl: I wasn’t involved, I wasn’t there physically, I was mad.

Mike: But you were in the group; you were a member of the group on paper, right?

Earl: Yeah.

Mike: Did you receive your money?

Earl: I mean… I got money, but it was from when I signed my advance with the label.

Mike: I ain’t never loan friends money; I give it to ‘em and I don’t expect to get it back. Even when he says, “I’ll pay you back,” I never expect it. If he gives it back, then hey, that’s a feather in his cap, but I don’t expect to get it back.

Earl: That’s where I’m always at. I’m never…I was never even mad about it. I was just… way more obsessed with preserving the friendship.

Mike: Listen, you know sometimes that’s a really an intense word, “friend.” You know sometimes during a relationship, a friendship, a friend’s gonna have to prove they’re your friend, and you’re gonna have to prove you’re their friend. You know, sometimes, the people we invest the most time in disappoint us the most.

Earl: Absolutely. This is the best way to summarize the situation.

Mike: In order to really be a friend to anybody, this is what I’ve learned in life and my experience only, not because I’m a genius, but that I’m saying some slick shit. I endured a lot of pain from this. In order to be a friend to anybody, you have to be a friend to yourself. If you’re not a friend to yourself, there’s no way you’re gonna have any friends.

Earl: If you’re stepping on yourself, then everyone else follows suit.

Mike: You have to be a friend to yourself. You know, ‘cause if you’re not a friend to yourself, you’re an enemy to yourself and if someone’s a friend of everybody they are an enemy to themselves. You know, you can’t be everybody’s friend, you can’t save the world, I learned this word: self-preservation. Once you do that, you can be friends with people, but how would you be a friend to anybody if you’re not a friend to yourself.

Earl: It’s like the same reason why they tell you to put the mask on yourself before the baby on a plane. Because if y’all both dead, because you was trying to help the baby, then what?

Mike: Exactly, you need to learn independence. You have to be independent – it builds character. You have to compete in life because if you don’t have no competition – no competition, no spirit, you know, you’ll fall under the slightest struggle… you know.

Earl: Absolutely – one thing I always try and tell dudes that are younger than me is that because of the Internet everyone can just be by themselves doing something, but the importance of a group is being able to have some sort of competition.

Mike: No doubt about it. You know, times have changed now because I grew up pretty much in the ‘70s, late, middle ‘70s. I met all my friends in the early ‘80s and met all my friends from fighting with them.

Earl: Yeah.

Mike: Most of them from the streets, we loved each other to death, we’d fight for each other, do anything…we even shot at each other. You know? We’re in different cliques, and we shot at each other. It’s really bizarre, if you think about it. It’s really bizarre. And I don’t know how it works, but it just works. It just works. Friends are very – that’s a very interesting word… human beings are a bad lot, y’know.

Earl: We’re some of the worst – yeah, I sit around and think sometimes about the constraints of being a human being.

Mike: You have to experience life. This world, That’s one big school out there. Outside is one big school. You know?

Earl: It gives you a Ph.D. in common sense.

Mike: Common sense is so very simple but very difficult to grasp.

Earl: Psh! Tell me about it. It’s crazy how many people are absent of common sense.

Mike: It’s all about the basics. If you can’t remember the small things, how are you going to remember the big things? Man- you know The mind is a real dangerous neighborhood to travel by ourselves. You think the hood is bad? Try hanging out here by yourself.

Earl: It’s the worst. It’s the worst, man – I always say you can always spot an addict by the person that can’t stop talking. ‘Cause they can’t be in silence. There can’t be an idle moment.

Mike: You can tell when an addict’s lying, too.

Earl: Always.

Mike: You know why, because he’s talking but that’s what the ego is meant to do. The ego’s mean, he’s gotta to be crushed. That’s what I need, I need my ego crushed. Smashed, obliterated. But my ego has given me everything that I have. My ego’s given me fame. My ego’s given me hundreds of millions of dollars, the most beautiful woman in the world – how can I let this go, are you fucking nuts? How do I crush it, how do I let this go?

Earl: Dude, ego is my career. Rap music is all ego.

Mike: How you let it go, you know? It has to be crushed, but it gives you everything you want, but it takes back so much more in return.

Earl: I feel like – I was lucky enough to get my ego crushed, when I was, like, 16. When I got sent away.

Mike: You know, you’re only 20; you’re not crushed yet.

Earl: True –

Mike: It’ll be in hibernation for a while, but it comes back, that’s just how it is – it comes back to help you, it gives you confidence. Gives you a full sense of courage. It just does all that stuff. But it goes too far sometimes. You know, you can’t control it. It’s all about being in control. Like, your mind – if you did everything your mind told you to do, you do some really strange stuff. You’ll probably be in jail, you’ll be in trouble. But you know, it’s all about control. We all have to control our feelings. That’s the thing that separates us from animals.

Earl: One thing that my mom told me that stuck so much that I feel like relates to what you was just talking about is there being only two real primal emotions – fear and love. And like, the only thing that can combat fear is action. And there’s two actions. There’s fight and flight.

Mike: There’s nothing to fear but fear itself. It’s an illusion of fear. Fear is an illusion. If you gonna die, you gonna die anyway; it’s not something to fear, fear is not gonna help.

It’s going to be over soon. Somebody’s going to die, or somebody’s going to get sick, someone might leave. It’s not going to last forever. You know, it’s going to be over soon. You know, the thought of that never enters my mind. This is the reality of life. I watched that movie The Notebook. You ever watched that?

Earl: I haven’t watched it.

Mike: Ah, young man, I don’t even know if you understand that stage of life yet. Very interesting thing about that movie, very interesting, it’s one of the movies that makes me really vulnerable. It makes me very vulnerable, because you work so hard for something and you don’t want to let it go.

Earl: Mhmm.

Mike: Let me see. For instance, this is really interesting. It boggles me sometimes, I always wondered the way we determine our age.

Before Julius Caesar, because he made a year 365 days, how could we detect our age? How did we tell? Methuselah was 900, right? So back then it was probably weeks or something. So how did we detect how old we were, determine how old we were before Julius Caesar was born?

Earl: Before there was like a year system?

Mike: Yeah, how’s that one, that’s pretty tricky now, you think? So we don’t know how old we are.

Earl: Everything was based on the sun. The sun. Setting, rising, over the course of the year, over the horizon.

Mike: Many moons, right? But when it comes down to really deep down, we don’t know anything. We don’t know anything. Nobody was actually there to tell, this is what actually happened. You know, no one can tell us; this is the real reason why Lincoln freed the slaves. No one can really say anything, they had to be there, you know, to tell us. When you think about it the world is, what? We don’t know how old the world is. But the written word is 6,000 years old. Six thousand years is a blink compared to the world, and the activity in the world. Six thousand years is nothing. Nothing.

Earl: That’s why all we got is right now.

Mike: Yeah, the moment. There’s no future in our past. Just experience. You know, we want to return to it, but we don’t want to close the door on it either. You know, that’s information so we don’t make the same mistakes. There’s nothing wrong with making mistakes, just don’t make the same ones. We don’t want to duplicate them.

Earl: I’ve got a quick question for you. One of the things I thought was really interesting you said in your documentary was: “There’s nothing like being young, and happy, and fighting.”

It sounds like such a contradiction, you know, to be happy and fighting.

Mike: Right you know this is interesting that you say that. That’s wild. Because when people see me and they say I’m coming back from what they say is the doldrums, or disaster, or something. But listen, you’ve got to be happy now. I’m not happy because I have received such success, I’m happy because – I’m not doing anything deceitful, I think, to my family. I’m successful because I don’t have to sleep with one of my friends’ girlfriends or wife or something. That’s why I’m successful, that’s success to me. I’m not dead, I’m not in the gutter – that’s success to me.

Earl: And it’s a profound statement because if you’re happy, you enjoy what you’re doing. And when you stop it just means you’re just going through the motions.

Mike: Absolutely, because you go through the motions and you are still successful. Until you run into someone who’s happier doing what he’s doing.

Earl: Exactly. So my question was at what point did you stop being happy? Like when did you start feeling that you were clocking in?

Mike: Wow, that’s awful, you know. Really early in my career, probably 14.

Earl: My last question, Mike, when you like achieve success like you have, how does that affect those around you – how do you get them to be motivated and not feel content?

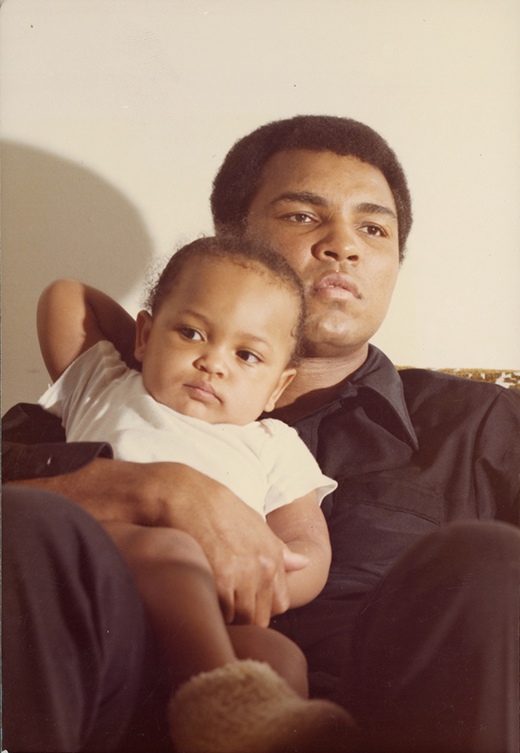

Mike: It’s just strange to me how I have such a profound passion for my kids. I think about Just wanting to protect them. – You think id ever let my son fight a 14-year-old kid or something like me that has nothing, never had nothing?

Earl: Because he comes from a different place. It comes from desperation.

Mike: I look at my beautiful son, he’s so beautiful and handsome. And I think what a guy like me would do to this face. I would choke it, take a chunk of meat out of his head, bite his beautiful face. I would hurt him, and I’m just looking at him and I’m thinking your dad was one of them animals out there. I don’t expect my kids to be “fighters”; my kids never lived in a condemned building with their family. Most of them are at Ivy League schools, their mothers are good mothers, you know, they do good stuff with them. I don’t want my kids to be like me, I don’t want my daughter to date the guy like me. You know, a guy like me success is to take care of my children to take care of their life and make ‘em cushioned. I don’t want them to be around a people like me. You know, success for me would be that they never have the opportunity of being in the presence of someone like me.

—

RETURN TO THE HOME PAGE

VISIT CITIZENSOFHUMANITY.COM