Sometime in 1976, the phone rang in the San Diego office of Warren Bolster, the editor of the recently relaunched Skateboarder magazine. The voice on the other end of the line probably sounded a little off. That’s because it belonged to a barely pubescent kid, Glen E. Friedman, who was doing his best to hide the fact that he was just 14 years old. He was calling from Los Angeles. “I’ve got some photos of Jay Adams skating a pool,” he said. “But but they’re really valuable to me, so I if I send them in you need to promise you won’t lose them.” Bolster gave Friedman his word.

Six weeks later, a small envelope arrived in Friedman’s mail. Inside was a check and a tearsheet from the new issue of Skateboarder. He ran out to buy the magazine and found to his astonishment that not only had the editors given his photo a full page, they’d also used the image as its subscription ad. “I just got the most radical picture that’s ever been in the magazine up to that point, and my name was on the bottom of it. It was crazy, and it was on.”

Friedman didn’t know it yet, but he just begun what would become a completely unique –and hugely successful –career. Over the next 40 years, Friedman’s work – from skateboarding to music and beyond — not only provided essential portraits of these bad-ass innovators in their purest states, it also introduced them and the cultural movements that they represented to the rest of the world.

Friedman’s first experience with getting his work published to be a typical one in that involved his signature combination of balls, talent, and a knack for showing up early to the party. By now, the story of how Jay Adams, Tony Alva, Stacy Peralta and the rest of the Zephyr skate team reinvented skateboarding in the mid-1970s by using surf techniques and then going vertical, has become part of pop culture lore, thanks mostly to Peralta’s 2001 Sundance-winning documentary Dogtown and Z-Boys. And within skateboarding circles, the Zephyr team cemented their collective legend at the Del Mar Nationals back in 1975. But Friedman was there first. He’d been skating with them a year before that, and by the time he called Skateboarder he’d already spent the previous year documenting the crew’s exploits with a pocket Kodak Instamatic. (Friedman’s first published image was on the first roll he’d ever shot of a skateboarder.) “I knew was I was onto something,” says Friedman, “because I was a skateboarder and I knew that it was something really fucking special that no one had even heard of, and that this crew that I was hanging out with were the only ones who were really doing it.”

Peralta’s film introduced Friedman to the general public. Wiry, intense, and fiercely intelligent, Friedman provided many of the Dogtown’s smartest and most entertaining insights. His sheer charisma and don’t-give-a-fuck attitude also made it clear why he was given the access to the Z-Boys, an insular, often combative crew who treated outsiders with merciless disdain, if not outright contempt. (They were well-known for throwing pieces of the decaying Santa Monica pier down on surfers from out of town.) And Friedman would have seemed like the perfect target: a mediocre skater who lived with his mom and stepdad in a good neighborhood who was a couple of years younger than anyone in the Dogtown crew. But he could hang, had stones, and, like his heroes Alva and Adams, self- doubt was never a problem.

“I’ve always had the confidence that what I do is the shit — I don’t fuck around,” he tells me. “You’ve got to have your own vision. You’ve got to show people what you’re doing and make it uniquely yours. Otherwise there’s no reason for Skateboarder to publish a fucking 14 year old, or for Jay and Tony to have me around if I’m just some rat who comes from the nice side of town, who’s just following them around like I’m kind of groupie or something. I wasn’t that. I was a fucking participant, and I was doing shit better than anyone else.”

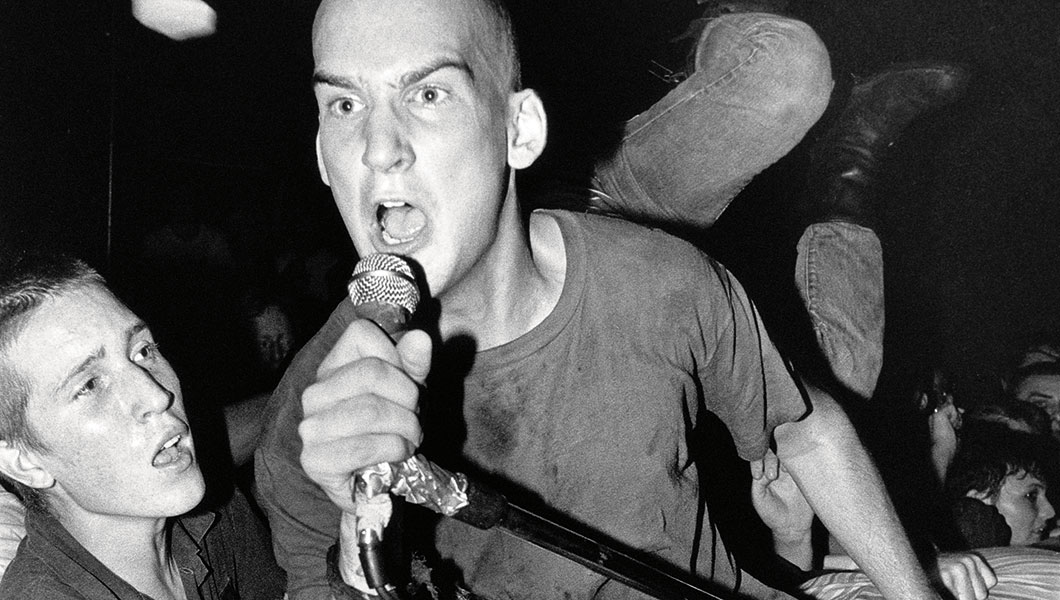

Friedman went on to become the definitive chronicler of the Dogtown days for Skateboarder, publishing countless photos in the magazine throughout the late 70s and early 80s. It was around this time that he found another source of obsession and inspiration: music, specifically the new underground genres that had begun to take shape just as skateboarding began experiencing a lull in popularity. It started with “hard-core punk” (a term Friedman loathes) and bands like Black Flag, Minor Threat, and the Misfits, some of whose members had obsessed over Friedman’s Skateboarder work.

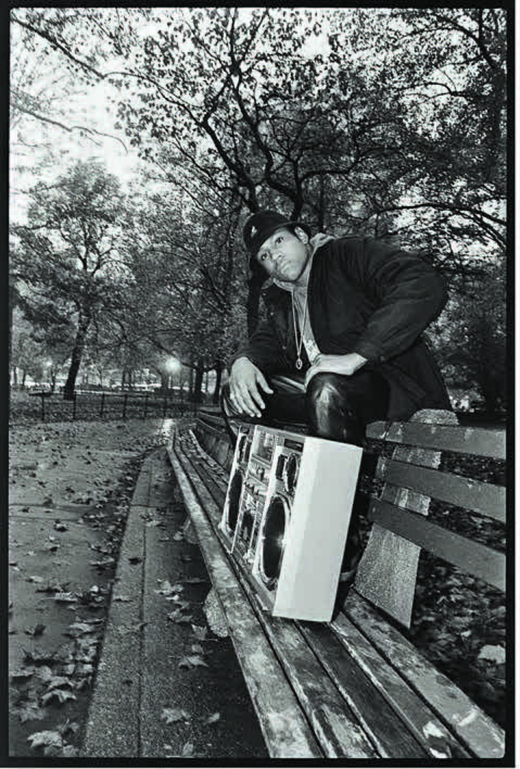

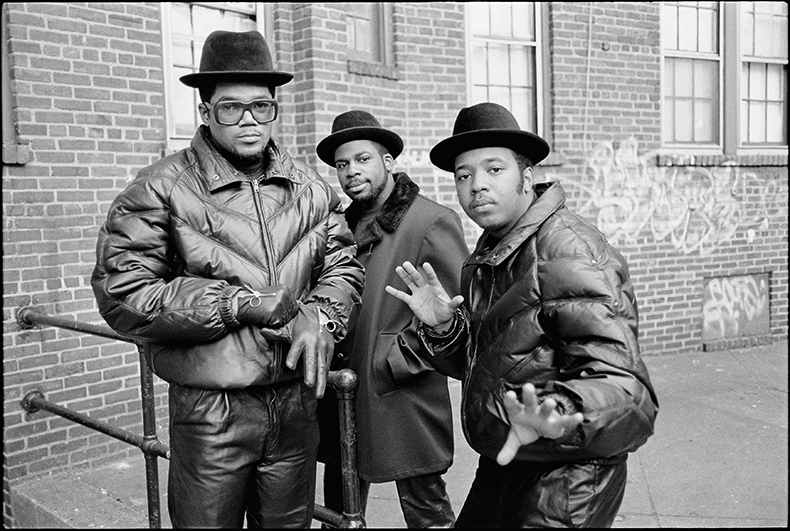

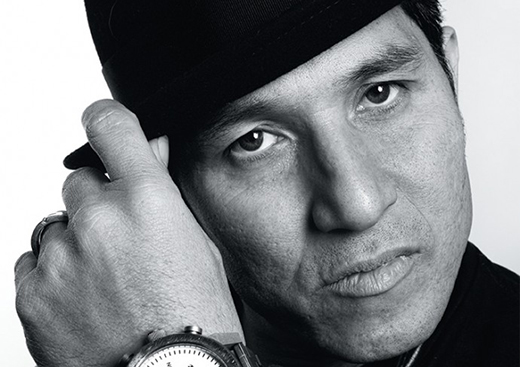

“People wouldn’t couldn’t see what I saw in the bands,” he says. “I told myself I’ve got to show everyone what’s really going on here,” says Friedman. “I thought It was my personal responsibility to the bands and subjects to take dope photos because that’s what I thought they deserved.” After making a detour to produce the first Suicidal Tendencies’ record, which went on to become the bestselling hardcore album of the 80s, Friedman went back behind the camera and began applying his signature approach to the emerging hip-hop scene. His photos of Ice T, Run-DMC, LL Cool J, the Beastie Boys, and other future hall-of-famers just as they were starting out, are now regarded, individually and collectively, as iconic portraits of a group of artists who, like Friedman, got there first.

September 2014 marked the release of My Rules, a coffee-table photo book and career retrospective that Friedman proudly touts as the definitive summation of his work with the icons he captured early in their careers. It’s a monster of a tome, featuring hundreds of photos, many of which appeared in print for the first time. And it doesn’t follow any established format. Instead of having a high-profile journalist write an introduction, include an artist statement and then focus on the images, which is the norm, My Rules has a whopping 22 essays written by the subjects themselves (as well as a few of Friedman’s colleagues) about the context in which the photos were taken. “I asked these guys to write something because I wanted readers to know how we got to the moment where we took those photos, what the inspiration was behind them, as well as where the performers came from and what got them there. I just wanted the whole thing to be just undeniable.”

My Rules is also a testament – and a reminder – of Friedman’s world-class talent, a fact that often gets second billing behind the usual chatter about how he discovered so many of these cultural phenomena in way before anyone else. The photos don’t simply hit all the required checkboxes of a great image (framing, composition, contrast, etc.); what distinguishes the work is the complete lack of affect on display by the subjects, all of whom share a similar quality that Friedman was the first to define.

“When I said hip hop was black kids’ version of punk rock, no one had said that yet, you know?,” he says. “All these things – skating, punk, hip-hop – belong together for a reason. They were fucking heroes, and they all shared the same attitude. I’m so proud of forcing those things to be together.”

Whether he’s shooting Tony Hawk or Ice-T or Henry Rollins, it’s immediately apparent that Friedman’s subjects trust him, and the resulting images are strikingly naturalistic. Even the staged portraits – which he started doing in the ‘80s – feel more like reportage. Friedman isn’t Avedon or Liebowitz, who, despite their brilliance, impose a certain interpretation of the fabulous people who visit their studios. His goal is more personal, more intimate, more aesthetically political: he strives to capture exactly what he finds inspiring in his subjects, to create a photographic interpretation of his own passion. And he’s never been some gun-for-hire who gets called in to make a singer or a skater or a rapper look cool. Once the publicists and managers are involved, he’s usually long gone. And if he doesn’t love what you’re doing and what you’re about, he won’t take your picture. It’s an attitude that has undoubtedly lost him countless money jobs over the years, but one look at My Rules provides no doubt that it’s all been worth it. Not a single picture in the book seems out of character, vague, or half-asses.

“The most important part of my work, why it’s good why it separates itself from everyone else’s is because it’s from the heart,” says Friedman. “I didn’t do it to make a living. I did it because I had to do it, because I loved what I was doing. I loved these artists because of how they inspired me.”

—