Though he’s captured frames of some of the most iconic performers, artists, politicians and even gangsters, it was snapping through rolls of film in London’s club scene in the ’70s and ’80s that established Derek Ridgers as a talented photographer. Ridgers was already in his late 20s when he trekked out to Skin Two, The Blitz and other London venues where British youth were rebelling and reacting to the right-wing agenda ushered in by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, with brash fashion steeped in fetish and the extremes of underground culture.

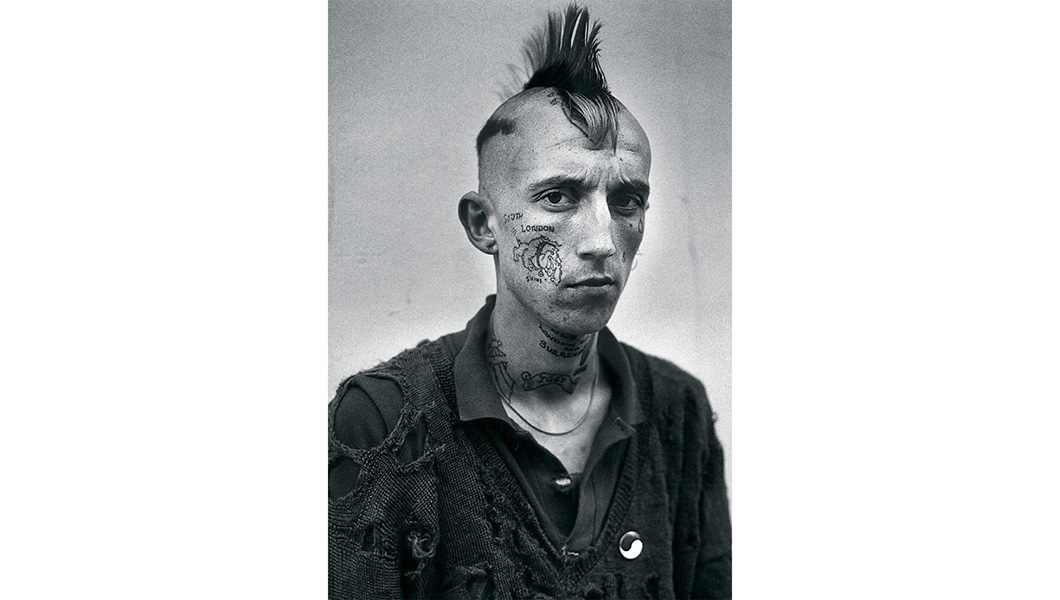

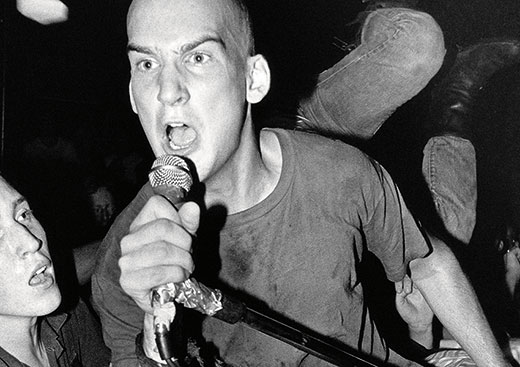

The youth Ridgers caught on film were stretching the boundaries of convention, sporting tattoos on their faces, necks and hands—something that wasn’t only taboo but often dangerous to have etched on your skin in public. Skinheads, new romantics, punks, goths and every other subsect of youth culture were commingling, with a total disregard for societal boundaries. It was ripe for documentation, and that decade has now been illustrated in a rich monograph titled 78-87 London Youth, in which Ridgers’ images and John Maybury’s text tell the story of the evolution, punch and panache of the disenfranchised and the historic scenes they inhabited.

How did you first get interested in photographing club kids, and were you met with any resistance initially?

Back in the 1970s, I was an advertising agency art director with easy access to a camera. By night I was a keen music fan and I started taking a camera to gigs, forcing my way to the front, pretending to be a photographer and shooting photos of some of the bands I liked.

In the beginning, it was simply an excuse to get a bit closer to the musicians themselves. But eventually I started to quite enjoy looking at the results as well.

Then in 1976, punk happened.

One really would’ve had to have been blind not to see how photogenic the punks were. So I turned the attention of my camera around and began to photograph the audience at the punk shows as well as the bands.

I really never had much resistance from any of the kids I was photographing. Maybe because I was keen on portraiture rather than reportage, I usually used to ask people first and if they declined, I’d just move on.

The only exception to that was in the early fetish club Skin Two. Most of the punkers didn’t want me there because they wanted to keep their fetishism private and they didn’t think outsiders should be around, let alone outsiders with a camera. Which is fair enough. I had a few of them offer me physical violence a few times—I remember one guy grabbed me by the throat. But my charm eventually won through. Plus, I’m quite a big bloke to be grabbing by the throat.

I used to get left waiting on the pavement for a long time by [Visage frontman] Steve Strange at The Blitz Club too. Steve Strange was already a legend in his own mind, even before anyone had heard of him, but having people wait out in the cold was all part of his shtick. But I’ve found you get nowhere in life if you take “no” for an answer. I simply wore Steve down with my persistence.

Can you explain the shock value of seeing kids with face, neck and hand tattoos back then?

I think that back then kids that chose very visible, very antisocial tattoos felt themselves to be ostracized by society and they were expressing themselves in one of the only ways they had. By getting themselves tattooed in that way they were saying, “I know I’m never going to be a conventional member of the society like you, and I don’t want to be.”

There was another, darker side to it as well. Most of the facial tattoos were done by unlicensed backstreet “scratchers,” and the majority of them in London were done by one man who, for a few cans of lager, would tattoo pretty much anything on anyone—provided you were young and male. Happily, I never met this guy, but I reckon an element of coercion could have been involved. Recently a guy that was subject to just such a facial tattoo from a scratcher—not sure if it was that particular guy—described the experience as being like a 30-year sentence.

He’s now hoping to get it removed.

At that time, the only people to have very visible, antisocial tattoos were people at the margins of social acceptability. Bikers, skinheads, teddy boys, prostitutes, rent boys, etc. I photographed all of them and never found approaching any of them difficult, but one does have to pick the right time, be polite and avoid being patronizing. If you have a big macho guy who’s in a bike gang, for instance, they are used to people looking away when crossing the street. They expect to be able to intimidate people. They don’t expect to be approached with an open mind and a friendly manner. Then my camera and its proximity often intimidates them and you get to see the real character. Often there is a real vulnerability in faces like that. They might take on a dozen men in a bar fight but they don’t always feel so comfortable with the close scrutiny of a camera.

What do you think was happening in England that spawned so many flamboyant and over-the-top looks then?

It wasn’t really what was happening culturally but politically. The key event of this time period was the election of the Thatcher government in 1979 and the circumstances that allowed such a cynical, right-wing government to take power. Margaret Thatcher had a very anti-trade-union, anti-working-class agenda, and a lot of the teenagers from that time didn’t think they would ever get a decent job and so they had very little to look forward to. I think their fairly understandable response to having, quote, “no future,” was that they may as well try to have fun whilst they were still young.

There was a tremendous flowering of young creativity under Thatcher which I don’t think we’ve ever quite seen since. Though unfortunately the country is still suffering from a lot of the rightwing policies she started—like the selling off of Council housing and the selling off of publicly owned assets. I was not a fan of Margaret Thatcher. Not by a long chalk.

What were you mainly shooting with for the photographs in the book and what were the challenges shooting in club settings?

Throughout the period I was taking the photos in the book I used a small SLR Nikon. First, a secondhand Nikkormat and eventually a Nikon FM. I used either a 50 mm or 24 mm lens, and I used a small and very underpowered flashgun, which I had mounted on a contraption I had made from a bent coat hanger. The purpose of the unconventional flash bracket was to get the source of light as close to the lens as possible and therefore reduce the effect of shadows.

Around 1984, I fell asleep on the train one night, on my way home from a club, and had the first camera and very unconventional bracket stolen. I simply reproduced it a second time, but the second version was never quite as good as the first. I used this wacky bracket that was covered in Sellotape right up until I started using digital cameras in 2004. I never once saw anyone else use that idea. I’m not sure if that means it was a bad idea? The big challenge to shooting in clubs is that it can often be very noisy, very dark and it can be very, very crowded. This aspect isn’t always obvious from my photos. This is why an awful lot of my photos are taken in corridors and stairwells. That was the only place I could see, make myself heard and stand far enough back from my subject to get them all in frame.

There’s a sharp contrast between punk now and even what Malcolm McLaren was selling as punk in the ’70s and what the average kids are seen looking like in your book. Can you explain the difference?

With the exception of the Malcolm McLaren/Vivienne Westwood stuff and a few items from BOY, the original punks only really had clothes they had made or adapted themselves. I shot extensively in the original London punk club—The Roxy—and there was a lot of augmented school uniforms, painted leather, stencil work and bin-bag clothing. The mass-market punk clothing from places like Miss Selfridge didn’t come until later. But not much later.

A lot of the multinational brands had wholeheartedly jumped on the punk bandwagon by the end of ’77. Which for the original punks, spoilt things somewhat. That was why a lot of them then rejected the punk look and went for what was, in many respects its antithesis. The new romantics and their high fashion and overdressed approach, which started the following year, was initiated almost completely by ex-punks.

Back then I don’t think the various youth cults you mention were seen as being a part of the overall fashion scene. That they were almost all quickly subsumed by the requirements of big fashion chains, that have to have something brand-new to sell each season, was not a surprise. But I was surprised by the speed that it happened. In ’77-’78 I worked close to Oxford Street and I saw the punk styles appear very quickly in Miss Selfridge. Even before punk had rolled out to some of the less hip provinces.

Nowadays the fact that so many aspects and styles of the past have become present-day fashion memes is to do with commercialism and nostalgia. And I suppose partly that some of those things, like the leather jackets of the bikers and rockers or the Dr. Marten boots of the skinheads or the parkas of the mods, always were destined to become design classics. A lot of the brands that were associated with the various youth styles are always going to endure because their qualities were intrinsic.

Who were you photographing back then that eventually became famous and did you see that “star power” in them?

The most famous of them all was Boy George, who for a while in the mid-’80s must have been as famous as anyone anywhere ever. I certainly did not think he had any star power before he was famous and he just struck me as quite a friendly bloke with a lot to say for himself. Everyone thought of themselves as being at the bottom of a certain trajectory and only a few of them were correct in that assumption. Quite a few of my photographic subjects went on to become pop stars for a while [Siobhan from Bananarama is also in the book], and in every case, you could have knocked me down with a feather if you’d told me they would achieve fame.

I was at art school with Freddy Mercury [then Bulsara], and we were friendly. It was the same with him. A guy less likely to achieve worldwide fame I couldn’t have imagined. Maybe I’m just no good at picking them?

I’d rather not pick a favorite, but what I would say is that there were some exceptional women around then. Myra Falconer, who is in the book twice, had a very unconventional beauty but I’d rather shoot her any day than a conventional beauty. And that’s not supposed to be a backhanded insult either—she always looked sensational.

What one image captures the title 78-87 London Youth to you and why?

Well I didn’t make the choice of what photographs were used in the book and I also didn’t make the choice for the cover photograph. Never in a million years would I have chosen that image to go on the cover of my book. But in retrospect I think it was a very good choice, and this factor shows why I am not a book designer. Kudos there to the books designer Rupert Smyth. So for one image that captures the title London Youth it would have to be that one.

But if you asked me to say which is my favorite image, it would definitely be the last one inside the book—the skinhead girl Babs, shot close to Carnaby Street in 1987. She was such a beautiful young woman with such sad, expressive eyes. And with the back-to-front tattoo on her cheek, I guess she was very mixed up and probably a rather troubled soul. I’m fairly sure she was a troubled soul because I have other photos of her taken in ’84 and she had her whole life roughly sketched out in an amateurish way on her arms.

I haven’t seen her since the day I took the photograph and I sincerely hope she’s had a happy and productive life. The look in her eyes is one that can bring me to tears. That’s why it’s my favorite.

—