HUMANITY: The Red Hot Chili Peppers, your sound, your style—everything is so L.A. What does it mean to be an L.A. native? What do you love about L.A.?

ANTHONY KIEDIS: Well, it depends on your definition of a native. I was born in the state of Michigan and actually selected L.A. as my city of choice at 11 years old. After coming out here to visit my father in the late ’60s and early ’70s, I kind of weighed the cultural experiences between the Midwest and the West Coast. I was really enchanted. Los Angeles put a spell on me as a kid with its energy, and I think it does that to people. There’s something about the desert, the electricity, the palm trees—just the promise that anything is possible. That hit me like a ton of bricks, and by 1973 I made my way to L.A., which was a completely different animal at that time relative to 2015. But there is that thread that it hasn’t lost, which is, this is where you come to explore your dream; whether or not the dream comes true, you fail miserably or somewhere in between, or you find another dream you didn’t even know was waiting for you, that thread maintains. I give credit to the enchanting vibe of this place, the inherent nature of Los Angeles and its valley, its mountains, its desert and its coyotes. It’s kind of a magical trickery.

HUMANITY: What do you think has changed? What do you miss?

AK: The things that I miss are kind of at an energetic level and they have to do with things moving at a different pace, where you can pay closer attention to your own thoughts and the things that are going on around you. When I first came here it was slower and more psychedelic. The atmosphere, the air, the streets, the walking, the skateboarding, the colors, the fashion, the music—everything moved at a pace where you could kind of take it in, contemplate and create; it was a more natural, organic interaction with yourself and things around you.

HUMANITY: What have been the lessons of fatherhood?

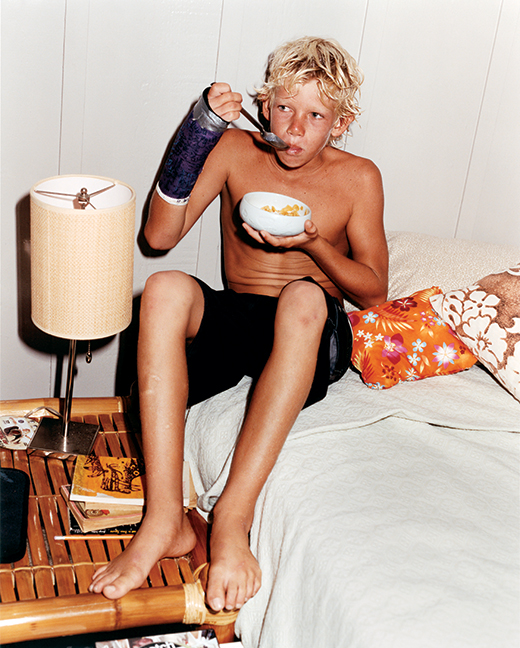

AK: Whoa! I’m right in the middle of that book, so more will be revealed, but … I guess one thing it’s taught me is that I never really knew what love was all about until I had a son. I was in love with all kinds of different things, but I never knew what that deepest, most sacrificial, unconditional, to-die-for love was really all about. I would do anything, give anything for the betterment of his experience. It’s taught me to care less about myself and more about someone else. The ongoing lessons are things like patience and not being judgmental and full of expectations, like: “Oh, I want him to turn out this way,” or I want him to be this or to be that. You kind of have to just see where he’s going and try to help him with that. It’s so hilarious, because we grew up on the other side of that dynamic, just wondering what our parents were tripping about all the time—“Why are they so hypersensitive and care so much?” And then you get to fatherhood and you understand.

HUMANITY: When a parent has the kind of success that you have had it can really add a lot of pressure. How do you not let your success overshadow him?

AK: That’s a great question. I guess it has to do with the way you act around your kid. I try to show him all sides of life and let him know where I come from. From the very beginning I let him know that whatever he wants in life he has to earn, because if I give it to him it’s not going to mean anything. And I think, even though he’s only 8 years old, he’s slowly starting to understand that it’s all about working for what you have, working for your experience, in order to enjoy and appreciate it and feel accomplished and fulfill your dreams. I never wanted to be one of those parents who just spoils; that doesn’t allow my son to go have his own trials, tribulations, failures, experiments and journeys of self. It’s totally on me to provide that. I think I’m also kind of lucky, because he was born his own person, like whenever I try to get him to do what I like to do, he’ll say: “Dad, that’s your thing, that’s not my thing. I want to do my thing.” So far he feels no pressure. It’s so unfair when children feel like they have to live up to something. They don’t have to live up to shit, they just have to live their own lives.

HUMANITY: You’ve been so open about your battles with addiction, and presumably addiction is hereditary. Is it ever scary for you to think about—that this may be a battle for Everly?

AK: It crosses my mind from time to time, but it’s not one of those weird lingering worries that I have. Every now and then I see a kid struggling with addiction, and I know their parents had struggled with addiction, and that will be interesting to see where Everly goes with that. But I don’t think it’s a guarantee that a child gets that particular gene. It’s kind of the luck of the draw. He’s chosen such a bizarre combination of his mother and father’s genes so far that I feel like it’s a real 50-50 whether or not he’ll end up dealing with addiction. I think he’ll grow up in a world where he’s not surrounded by addictive behavior, or addictively inspired dysfunctional behavior, so hopefully he has kind of a strong emotional basis to begin with, a solid family and emotional foundation to fall back on. If it happens, it would be difficult but like many bridges, I’ll cross that one when I get to it.

HUMANITY: It’s pretty well documented the relationship you had with your father, and what you were exposed to at a young age. What are some of the lessons you learned that you’re applying in your relationship with your son? And then on the flipside, the relationship you had with your mom was definitely more traditional. Talk about that balance, and what you’re applying that you learned from them to parenthood.

AK: I’m such a different person at this point in my life than my father was when he was raising me, but there are still tons of similarities. For example, I’m a single father, so it’s just my son and me living under this roof. However, he was just very wrapped up in his own lifestyle when I was young and impressionable. He had very creative interests, but I think it’s about what not to share with a young person. He wasn’t able to slow down and contemplate how fragile a young heart can be. It was too much too soon. Me raising my son is a wildly different experience. We live in the countryside, we wake up next to the ocean, we do homework together in the morning, we exercise together, we go for long walks together. It’s kind of this other-end-of-the-spectrum experience compared with my own childhood. And my son seems to love it. He really thrives on it—he thrives on the fresh air, the ocean, the trees and all this stuff I did not grow up around. I always thought he would want to have a place in the city, and he says: “Why would I? It’s so great out here!” I still introduce him to some things my father introduced me to but live more of the reliable life that my mother offered me. In retrospect, if I look at my mother, she went to work every single day of her life. She’s so together and she just inspires me. She travels the world and takes care of her loved ones, whereas my father was much more that hippie, free-flowing, maybe-I’ll-work-maybe-I-won’t but was part of a lot of great experiences. And my stepfather was probably the most honest and caring person that I’ve ever known. He died very young, but his influence on my family is visible every single day. So I guess I’m trying to give Everly a little combo platter.

HUMANITY: What do you think the difference has been this last time—why has sobriety stuck for you now?

AK: It’s been a complicated run for me. As soon as I got introduced to the concept of getting well from an addiction I loved it, because I had done this using thing to death, so when I got offered a solution, I jumped all over it years ago. But you know, it takes work and dedication, and after five years I ended up relapsing, kind of going in and out for the next five years, and that’s fucked up. So when I finally got back into it in 2000, I loved being sober, so I embraced it and I realized I have to do some things differently than I did the previous time. I made little adjustments and I tried to surround myself with like-minded people, so that I have constant reminders that the more energy I put into that, I get back 100-fold.

HUMANITY: You said something that stuck with me, that when you first went to rehab you’d see all these people that looked so different on the outside from you, but you’re actually able to see yourself in every one. And it helps with finding compassion—it’s a simple idea, to have compassion for someone else, but a rare practice.

AK: My ability to actually experience compassion comes and goes. There could be part of the day where somebody passed me up on the PCH and I’m like, “I’m going to teach them a lesson.” Something idiotic and chaotic like that. Or if I just slow down a little bit and get into that mindset that I don’t know what that person is going through. If you just pretend like everybody out there is a family member, it’s really hard to go to that place where you’re like: “I’m going to get you.” It’s about checking yourself and slowing down a little bit. I go to meetings, so I can slow down and listen to the story of somebody else. Maybe a 21-year-old girl who’s been shooting dope for the last two years of her life and is in complete hell and lost herself and then she gets a week clean and she’s in a meeting sharing about not being able to find a vein in her neck. And I’m like, yes, I do remember that desperation. That’s no good. I now feel connected to this person because I see and feel the suffering in the fact that I got one little glimpse of not having to live like that today, in this little 24-hour segment. So my life kind of depends on showing up and listening to other people’s experiences, and maybe that gives me an opportunity to actually feel a moment of true compassion. It’s work.

HUMANITY: How has your creative process changed over the years?

AK: It’s strikingly similar in many ways. There are so many different stages that I have to try and be available in the creative process. We’ll have band practice and improvise—I listen and kind of lose myself and find melody and find rhythm in the moment. Then there’s the songwriting process, where the guys will give me an instrumental recording and I have to sit with that music. Then there’s the part where you’re just in the car and you get an idea, and you have to pull over and work on the idea because that idea might never come again. You’re on an airplane, or a train, whatever—whenever you feel that little tiny cloud moving through you that has some energy and some ideas. One thing I learned is to seize that, because you can say: “Oh, I’ll remember that!” Sometimes I’m out there waiting for waves to come and I’ll get a great idea or a mediocre idea or maybe a couple of melodies that string together, and I’ll sit there and try to sing it over and over a hundred times so that I won’t forget. And then I get into my car; I’ll break out the phone and record it. That part has changed, being able to record everything on your cell phone is different than it was 25 years ago, when you had to have a funky little tape recorder with you wherever you went. I’m a morning writer—I get up in the morning, clear the house out and get out my notebooks and my pencils and my CDs and my boom box and I’ll just sit there and write. I find that the more regimented I can be in putting a few hours of work in every day, the more benefits I reap when it comes to writing good songs. It’s like a painter that forces himself to paint every day, just hoping that could be the day it happens. I believe to be good you have to work hard. It’s the same with Flea; he practices constantly. He’s been playing bass his whole life, but he’s no good unless he practices every day.

HUMANITY: Do you ever feel pressure about getting older and still being a relevant musician?

AK: Pressure, no. Aware that it’s difficult to maintain relevance, yes. I’m hyper aware of that. We don’t have that pressure to be the next cool thing, because we’re never going to be the next cool thing. We’ve done that. I pay attention to my favorite songwriters, and they’re way smarter and way better at writing songs than I could ever be. You know, like Paul McCartney, Neil Young, Randy Newman are all just phenomenally gifted singers and songwriters; however, none of them have really been able to create real greatness in their older years compared to what they were doing in their 20s and 30s. And I always wondered, “Why?” They’re still talented, they’re still smart, they’re still in love with music; they haven’t given up in any way, shape or form, but they’re not writing songs like they used to. Every now and then they’ll stumble upon a gem, and their live shows are still incredible. I guess it’s a cycle—it’s almost impossible to write music that crushes and touches people’s hearts in that way once you’ve made it. Once you can afford a house, another house over there and another over there, it’s like that weird fine line of comfort changing you. You look back at the lifestyle of all these people back when they were writing songs that you and I will go sing later today while we’re driving around in our car, and they weren’t that comfortable. And it’s just, how do you stay great and relevant and interesting and as good as you used to be when you’re that comfortable and have other responsibilities and distractions? It’s hard. But it gives me hope when I hear a Paul McCartney song that he did in the last couple of years that reminds me of who he is deep down inside. Not that he’s got anything to prove—he’s already given the world more great songs than anybody else I can think of, but it makes me happy that he’s still able to do it.

HUMANITY: It must be a hard thing to stay humble and grounded. I read in your book about the importance of going to AA meetings and stacking chairs afterward—surprised me that you do that …

AK: Humble and grounded some days, and then some days arrogant and up in the clouds. The chair stacking is more meaningful, more powerful, more relevant, more life saving than you could ever imagine. I’m laughing because my commitment is stacking the chairs, and I cannot tell you the amount of satisfaction I get from those chairs—that’s my single-minded purpose for this evening, making sure that those chairs are stacked. It’s just being of service, being one of the wolves in the pack. It’s being present for myself and for somebody else. It’s all work in progress. I have good days where I’m connected to my humility and it feels amazing, and I have other days where I just cannot find my humility and I walk around expecting the world to fall at my feet. And that’s no fun.

HUMANITY: Do you have a mantra?

AK: I do lean heavily on the desire to be a kind person. Which takes work for me, because I can be confrontational, and I can be full of myself, but I do have the sneaking suspicion that at the end of it all, when everybody stops, the degree of your kindness is really going to be the thing that shapes your next experience. That’s what I’d like to attain within my active and silent mantra.

HUMANITY: What’s happiness to you?

AK: I find happiness in the simplest, littlest things ever. It’s nothing to do with grandiosity but everything to do with simplicity. For instance, holding my boy this morning—doesn’t get any better than that. That’s my happiness. Watching the sun come up, that’s my happiness. Being on my surfboard, touching the surface of the ocean, that’s my happiness. Popping in a CD with the new song my band’s been working on, that’s my happiness. Calling my father, hearing his voice on the phone, getting excited about calling him, that’s my happiness. Reading a book for my son at dinner, that’s my happiness. It’s kind of everywhere, all around me, if I’m right with myself. If I’m wrong with myself, I’m not finding it anywhere.

HUMANITY: What are you most thankful for?

AK: What am I thankful for? Everything. It’s all a gift, it’s all happening for a reason and I’m thankful for all of it. I complain about it: I got sick two weeks ago, and I never get sick. I was so pissed off—I can’t surf, I can’t sing, I’m achy. But now I’m thankful I had two weeks to think about this. Two weeks of not running around like a chicken with my head cut off. I just slowed down, chilled out, stayed home with Everly, worked on lyrics. So in retrospect maybe I needed to get sick. I’m thankful for everything.

—

RETURN TO THE HOME PAGE

VISIT CITIZENSOFHUMANITY.COM