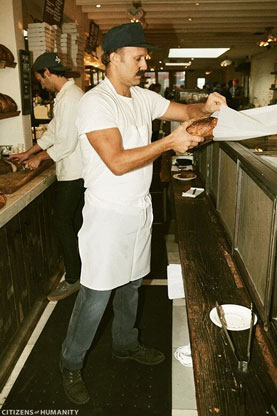

As a young boy, Pierre would wake up to the smell of warm croissants, bread and biscuits wafting through the window from the family bakery below. “To see that you can do something with your hand and you can give life to a cake, that was like magic for me,” says the 55-year-old chef, who would help his baker father in the kitchen. His mother, who managed the shop, warned him against becoming a patissier. “She said it’s too hard and you’ll never find a wife who wants this life,” recalls the Alsatian native.

But the 9-year-old’s mind had already been made up, and a life dedicated to confectionary pursuits wasn’t a choice but a calling—one that eventually garnered him the title of France’s youngest Pastry Chef of the Year, and the distinction of Chevalier of the French Legion of Honor in 2007. In 2016, Hermé was named the World’s Best Pastry Chef on the illustrious San Pellegrino World’s 50 Best Restaurants list.

Fixated on the idea of working in a kitchen, a 14-year-old Hermé enlisted the help of his grandmother to respond to an ad in the local newspaper for an apprenticeship with esteemed patissier Gaston Lenôtre at his namesake Parisian patisserie. Hermé stayed in the role for seven years, determined to learn as much as possible and, above all, to succeed. “I was anxious not to go back to Alsace with my suitcase and say, ‘Oh OK, I failed, I was fired,’ ” he says.

It was here where Hermé’s fascination with modernizing France’s beloved macarons began to take shape. “When I started at Lenôtre I didn’t like the macarons because they were very sweet. They were just two biscuits with a little bit of filling to stick together the two biscuits,” says Hermé, who began to experiment with the traditional formula he had been taught. “I tried to find a way to make the taste more powerful.” The solution, he discovered, lay in adding more garnish in between the delicacy’s two crispy shells, composed of egg whites, sugar and almonds. Going even further off script, Hermé began to incorporate more unconventional flavors and combinations such as rose, pistachio and lemon, deviating from classics like vanilla and chocolate. “I developed a new style of macaron,” says the pastry chef. “There was a big lack of creation in this field.”

By age 24 the rising sweets star was helming the pastry department at Parisian luxury food emporium Fauchon before moving on to consult for the storied macaron brand Laduree. In 1998, Hermé debuted the inaugural Maison Pierre Hermé Paris boutique in Tokyo at the Hotel New Otani, followed by his first storefront in Paris three years later on Rue Bonaparte. In 2008, the first Macarons and Chocolate boutique bowed on Rue Cambon in Paris, dedicated to the brand’s offerings—chocolates, macarons, cakes, ice cream and confectionary gifts—with the exception of fresh pastries and viennoiseries, which are sold at the brand’s flagships (Rue de Vaugirard and Rue Bonaparte in Paris and Aoyama, Japan) and Café Dior in Seoul, South Korea. Today the company has grown to 45 storefronts in 11 countries.

But no matter where you are in the world, the pleasures found inside the carefully curated world of a Maison Pierre Hermé Paris boutique are one and the same. Rows of chocolate bonbons fill the glass vitrines like jewels on display, competing for attention with the house’s Technicolor macarons in best-selling flavors including milk chocolate, passion fruit and ispahan, composed of rose, litchi and raspberry. “I have to give our clients the same experience,” he explains. “It’s about giving some pleasure to these people coming into our shop, taking time to choose a macaron, a cake, chocolates. That gives them pleasure. That’s the only goal.”

Hermé approaches his craft from the standpoint of both an artist and baker. The starting point is a mental image, which he sketches on paper, like an architect drawing up a blueprint. “I can explain to the people working with me in the kitchen how the layers come together,” he says. After imagining the product in his mind, he’ll write down the recipe. At any given moment, Hermé and his team are working on 30 to 40 new creations. Inspiration strikes in many forms, be it a conversation he had or something he saw or read. But most often it’s the ingredients that lend themselves to a creative spark.

When it comes to satisfying his own sweet tooth, Hermé still finds great enjoyment in pastries, whether made by his own hand or by other sweet makers. “It’s always a pleasure [to eat sweets], including when it’s work,” says Hermé, who is especially fond of ice cream. “It’s one category of product I prefer because there’s a lot of taste and texture.” Indeed, gelato and ice cream have been part of his confectionary endeavors from the beginning, reinterpreted in some of the brand’s iconic flavor combinations including ispahan and infinement chocolat.

He’s also a connoisseur of French wines and draws parallels between a vintner’s work and his own. “It’s a very similar craft to mine because it’s a way to combine different flavors and different smells. So there’s a lot to learn from this.” Other passions include art, design, contemporary architecture and travel—the latter of which often translates into new creations in the kitchen. “Traveling always enriches my knowledge about ingredients,” says Hermé, who finds savory foods as inspiring as sweet ones.

His latest obsession is black lemon, which he came across in a little shop in Corsica. A popular ingredient in Persian and Middle Eastern cooking known as loomi, its English translation is a misnomer: The fruit is actually a ripened lime that’s boiled and then sun-dried, turning completely black. “You use the inside, the peel and the zest,” says Hermé of the flavor-packed fruit, which can be used whole, sliced or ground and has a sour profile. The ingredient has already worked its way into Hermé’s macaron lineup, making its debut this winter alongside the seasonal foie gras and hazelnut combo. A black lemon tart is also in the works.

The secret to succeeding as a pastry chef, says Hermé, is knowledge. “When you learn to do pastry, you need to start like a student. That means working in the kitchen but also working at home and doing some reading about the history of the craft, the history of people in the business.” Knowledge of ingredients is crucial, too. “It gives you power and the base to be creative. You can taste the ingredients, but it’s not enough. You need to know about who makes them, where they grow, when it’s in season,” explains Hermé. For the last two years he’s been fixated on flour and the idea that it plays more than just a functionary role in his offerings. “I’m convinced that flour can also bring more taste,” says Hermé, who is focused on discovering the flavor nuances in a broad range of flour varieties, including rice, buckwheat and chestnut.

Hermé doesn’t feel any pressure to maintain his status as one of the world’s best pastry chefs. “It was a very nice surprise and good encouragement, but I did nothing special,” he says. “Every day I work toward making the products in the stores the best we can, so the pressure is always the same.” What he does feel compelled to do, though, is pass down his knowledge to the next generation of pastry chefs. “In all artisanal crafts this is the only way to develop and also enrich them,” muses the patissier. “This is an obsession, and my goal.”

—