GUSTAVO DUDAMEL: How is everything?

HUMANITY: Everything’s good. We’ve wanted to do this for such a long time. So you became music director here in 2009, and it’s pretty safe to say you had your choice of anywhere in the world, so why did you accept the job here in L.A.?

GD: I think it was a period of an explosion of things that happened to me. I won the Bamberg competition in 2004. It was a German competition, and then internationally I ended up becoming the symbol of a young conductor. I did have a position before becoming music director here, with the National Orchestra in Sweden, but I came here to visit and I didn’t understand anything. I came to Los Angeles; it was my first time here and I didn’t connect with the city. I watched the Hollywood Bowl for three days and it was like, “Wow, this is so big.” Musically it was wonderful, but the city was not connecting for me. But the second time it just clicked and I made a real connection with the orchestra.

I remember musicians coming to my dressing room to say, “What a wonderful way to make music—let’s keep doing this,” and at that point it was not a difficult decision to make. I think the conditions that Los Angeles brings to artists is amazing, is fresh, is new, is open. We have this wonderful hall, we have an incredible audience, the Hollywood Bowl. The orchestra is fantastic. We have been really working to create a personality together, so it was a combination of many elements. I started here when I was 29—I was a baby. It’s been a real time of growth for me and I’m proud of what we have done and for our future.

HUMANITY: Outside of the music, what do you love about living in L.A., and what do you end up missing most about home?

GD: Do you say diversity? Is that the right word?

HUMANITY: Yes.

GD: I love the diversity of the city. As a young person, it is really interesting and important to me. It’s inspiring how the community connects with the orchestra, with the art. How symbolic art is to this community. I think for a long time the world had a misconception of Los Angeles—it’s so much more than Hollywood. Los Angeles is full of so much culture and opportunity. We have to remember that in the middle of the 20th century a lot of artists came here—great artists, painters, philosophers, musicians—and the same thing is happening right now.

HUMANITY: What do you miss most about home?

GD: A lot of things—family, of course; friends; and the energy. But I feel Los Angeles has a similar energy to Venezuela; it’s one of the things that’s connected me with Los Angeles. There is this kind of energy—the traffic, the people.

HUMANITY: What do you think have been the major challenges so far in your tenure here?

GD: Challenges? Well, artistically, of course, always, and today I have more. It never stops. It’s kind of insane, because you get older and your brain opens, and opens, and opens—you’re searching for new things, new challenges. Of course we have many challenges to build on, as I mentioned: to grow our audience here; even though it’s big, and we are proud of that, we want to get bigger. For example, this season at the Hollywood Bowl I found the connection. It’s not the same to be in a hall with the perfect acoustics; it’s really not the perfect environment to play classical music, but I found that it’s perfect because it has the access. Every night we had 11,000, 12,000, 13,000, 15,000 people listening to classical music. So it’s these kinds of challenges, and every year we want to bring a younger audience, so we have to do programs that connect more with them, keeping the condition of the classical music but bringing something new. I think it’s fun.

HUMANITY: This kind of goes to that thought. In Venezuela, the idea of El Sistema is to bring music to all, correct? Music education for any child who has the desire?

GD: Yes. It’s about inclusion. The program is more about inclusion than the music even. It’s to include children in art, and that is beautiful because at the end of the day art is beautiful, you know.

HUMANITY: I would think it must be challenging to connect to those people who might not necessarily be seeking out classical music or even thinking it’s for them. Is that important to you to try to open up to that audience?

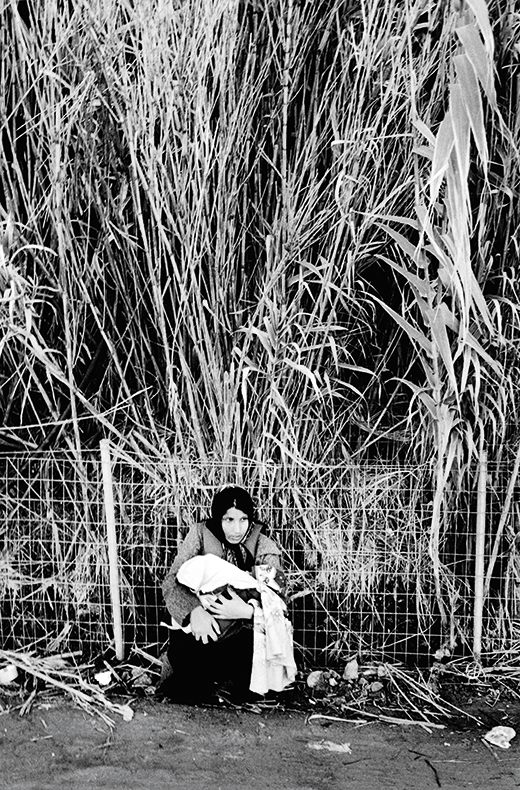

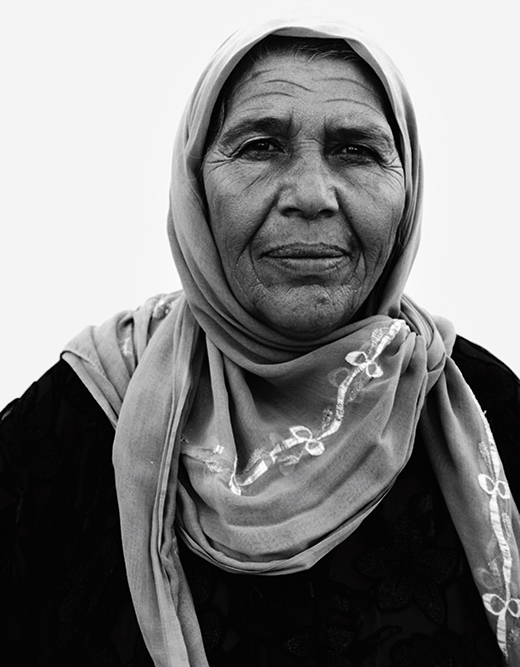

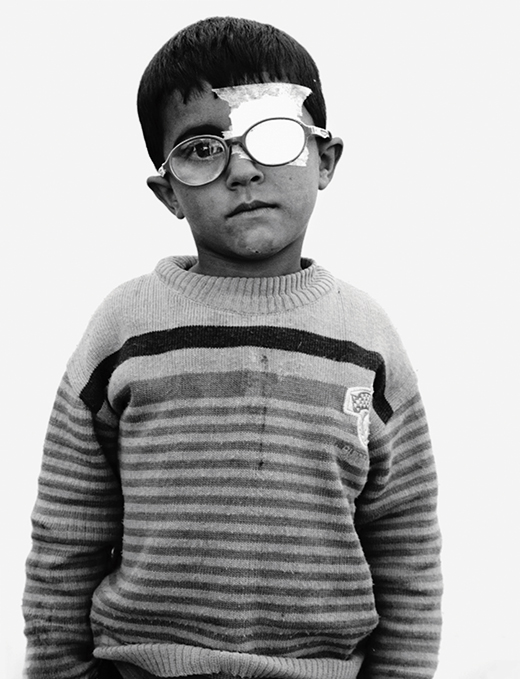

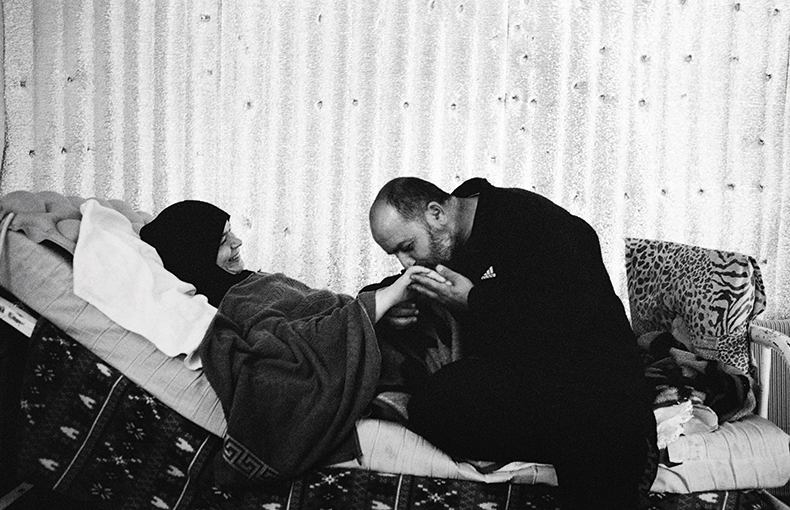

GD: It is, and we do in many ways. First with our programs, creating greater access, doing concerts for all communities; we also have YOLA, which is our youth orchestra, similar to Sistema. That connects with parts of the city that see classical music as very distant, or something very elitist. These may be the children of parents that are working very hard to support their families; maybe some of them are undocumented. These can be tough conditions for anyone, much less a child. Music and art can be healing; you see how the programs can change a child, change a family.

I received a letter about a month ago, a father writing to us saying, “Thank you. My daughter is going to college. She’s confident, helping other people, even writing poetry.” It’s how things can change through music, and imagine it’s not only one child you are impacting, it’s all the people around them—their family, their community. It’s an interaction that is amazing.

HUMANITY: L.A. has a huge Latin population, and you are a huge cultural figure here. A Latino who’s a cultural figure in Los Angeles—it’s a lot of responsibility …

GD: The important thing for me is how art can be an important symbol for people and inspire them. Last week I was at the White House for the National Medals for Arts and Humanities. I gave a speech about the importance of art in society, and how we must bring art to the heart of the community. Unfortunately the simple fact is that when we have a crisis we cut art immediately—cutting the one thing that can connect all parts and levels of society. It just sends completely the wrong message. So when we talk about a symbol or a hero of the community, it’s more about being a vehicle or vessel of hope to people, a new vision of life, a new concept of community. So if life gives you the opportunity to be a hero and a symbol, then it’s something one must not take lightly.

HUMANITY: You mentioned wanting to expand the audience, and it seems like more recently you’re starting to bring more and more guests in to collaborate with. Is this something we will see more and more of? Any insight into ideas you’re exploring?

GD: I have many. During the Super Bowl we had our children there playing with Coldplay. I’m very good friends with Chris [Martin], and we have plans to do crazy, exciting things. I’ve had conversations with Beyoncé. We both said, “Let’s do something together,” so these kind of crazy things like what we have done with Rubén Blades or Juan Luis Guerra—there are so many people and ideas to create these bridges between all the different kinds of music that exists.

HUMANITY: Because you look at someone like Beyoncé or Coldplay, they’re known by the masses, so it almost brings in a whole new audience who might not otherwise be interested …

GD: Absolutely. They have an audience that is not this audience, and this audience is not their audience, so imagine that mix of things you create, and I’m very open. People think that classical musicians are crazy, only caring about reading classical music and philosophy. No. I love to dance—I just love music. I’m obsessed with the Beach Boys and Brian Wilson; the other day I went to see Sting and Peter Gabriel. This was the first time that I saw Peter Gabriel and I was amazed. I want to do something with them. These kinds of things.

HUMANITY: Who were your musical heroes growing up?

GD: Well, my father was one of my heroes because I wanted to play salsa. It was my dream to play trombone like my father and to play in a band, to have people dancing as I played. In my family, of course, my father and my grandfather, they are my heroes. My maestro, Antonio Abreu. He created this concept of art as an element of social change. He is a hero. And just so many more …

HUMANITY: What about bands or even musicians?

GD: Wow, my god, many of them. Brian Wilson, I think he’s one of my heroes, in the way that he saw music in that moment, especially with Pet Sounds; he connected with song cycles that Miller, Schubert, Schumann were writing in the 19th century, this new way to think. Juan Luis Guerra; I love Pink Floyd; so many …

HUMANITY: What do you think it was about Sistema that was able to foster such talent? What was the environment like to learn in?

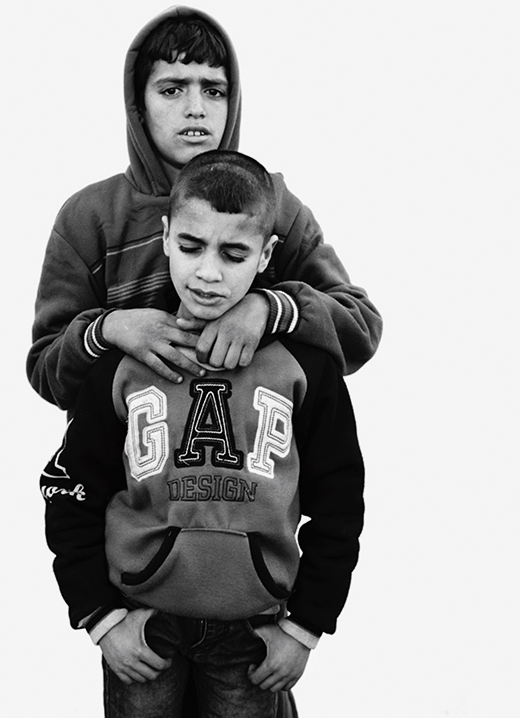

GD: In Sistema you don’t grow up individually, you grow up as a team, and that is great, because you are creative together with others. It’s really an example for society, that we can be better together. We live in a very “individual” society, and that is why we are as we are right now, where the strong beat the weak, and it shouldn’t be that way. I think at Sistema what’s great is that if somebody was sitting next to you and was not as good, you helped, and I think that is my treasure as an artist—that I feel. It is not my knowledge about music, because you can learn music; that is not difficult. It takes time, but it’s not difficult. It’s something technical, this kind of understanding of people. That is why I say to the orchestra, “I was sitting there.” I know I have to read 200 eyes every time that I arrive here, and every one of them have their own reality, family; some of them arrive sad, tired, bored, happy, excited, and then you have to combine all of that and inspire them to play a piece that they have played 1,000 times before with different conductors, so this is the thing, the understanding. That is the thing that for me a conductor is; it’s not about music only. Yes, music is the main thing you are doing, but it’s a lot about how to work together. A conductor is nothing alone—you need the musicians in front of you to make it work.

HUMANITY: I think throughout your life definitions change—definitions of words like success or accomplishment—so now for you, what gives you a sense of accomplishment? What makes you feel like a job well done? What is success to you?

GD: What is success to me? Wow, what a good question. I think when you are young you believe that you can do everything and that you are right in everything that you do. You are kind of arrogant in a way, but my success I think is to understand right now that there’s a lot of space, a lot of ways to go in my life. The things that I thought I was doing really well before right now make me think, “Why do I want this sound? Why do I want to make this faster or this slower artistically, technically?” And that is a success for me—to open my mind, to have the knowledge to see there is more.

Also, another success is how we are participating in community. If one child out of a thousand can change his or her future for the positive in our programs it’s a success, and it’s not going to be only one. In Venezuela it’s been hundreds of thousands. In Los Angeles it’s in the thousands. The other day I went to Sweden; I started a program there when I was music director in a community of immigrants who were living in ghettos about 30 minutes outside the city. These people had never before been to the center of the city, and now the program is huge—more than 7,000 children participate. I’m no longer there, but I’m so proud of what has been accomplished. It’s a real success and I’m part of it and I’m a part and a product of that movement that Sistema and programs like these create.

HUMANITY: I have a 2-and-a-half-year-old, and becoming a parent changes you in so many ways. So my question is, since becoming a parent, what are the major changes you’ve noticed in yourself?

GD: To have a child is the most beautiful thing—it’s a miracle. If you don’t believe in miracles when you see something that you create, in a way, together with your wife or your husband, whatever, it is a miracle completely. That is the first thing, but what we have lost in our society, which is so important, is faith. We have to recover faith, but it’s a scary time. Sometimes you see the world, what is happening in it, and it’s a lot … we cannot predict what will happen. But at the same time, it’s this paradox. It’s beautiful because, again, kids bring new light, and I think having Martin, for me, it is the hope. You go into parenthood thinking you have to teach your children about everything, but it’s quite the opposite; your kids really end up teaching you how to and what to do through those moments all the time, and for me that is a miracle. My energy and my hope is bigger right now having him next to me, and it’s all the motivation you need to work together to build a bright future.

HUMANITY: With that idea, you’re a cultural and world icon, and that can cast a shadow for a little kid to follow. Have you ever thought about how you will support him to not feel overshadowed by your accomplishments?

GD: First of all, I think he’s proud of me. I feel that. He likes to come with me to work, listen to the music, and I’m proud of him. This feeling is mutual, so whatever he ends up doing I will support him and he will always know his father is in his corner.

HUMANITY: You’ve mentioned in several interviews that music saved your life. How so?

GD: Well, I come from, let’s say, a difficult area in my town, a beautiful one by the way, but difficult. I have friends that are not anymore because they took the wrong way. Fortunately I got an opportunity; my parents were very young when they had me, and my mother was also a musician. She sang in the choir, so I was surrounded by music all the time, and music saves. And it has all my life. When I’m sad I go to the podium and it’s like I’m instantly happy. It’s a wave of energy, of beauty. Music saves my life every day. Not only at the beginning of my life, but every day since.

—