Artist Suzannah Sinclair spent the past year painting 12 postersized watercolor portraits, all of beautiful women sourced largely from vintage men’s magazines. The images fill a wall, which is what she had intended. Each woman depicted somewhat resembles a young Jane Fonda or Jane Birkin—the well-heeled hippie look. Mostly, they are blond or brunette, some with glimpses of red in their hair, and six of them are probably nude, though it’s hard to know for sure given that Sinclair only shows their heads and shoulders. None of them are quite smiling.

The one called Bonnie, leaning against a wooden beam with sun hitting her hair, comes closest. Paige, who’s in some sort of garden, is the next closest. “They are all almost just the same, different personalities of the same girl,” the artist reflects. “Not awake but not sleepy, not happy but not sad.”

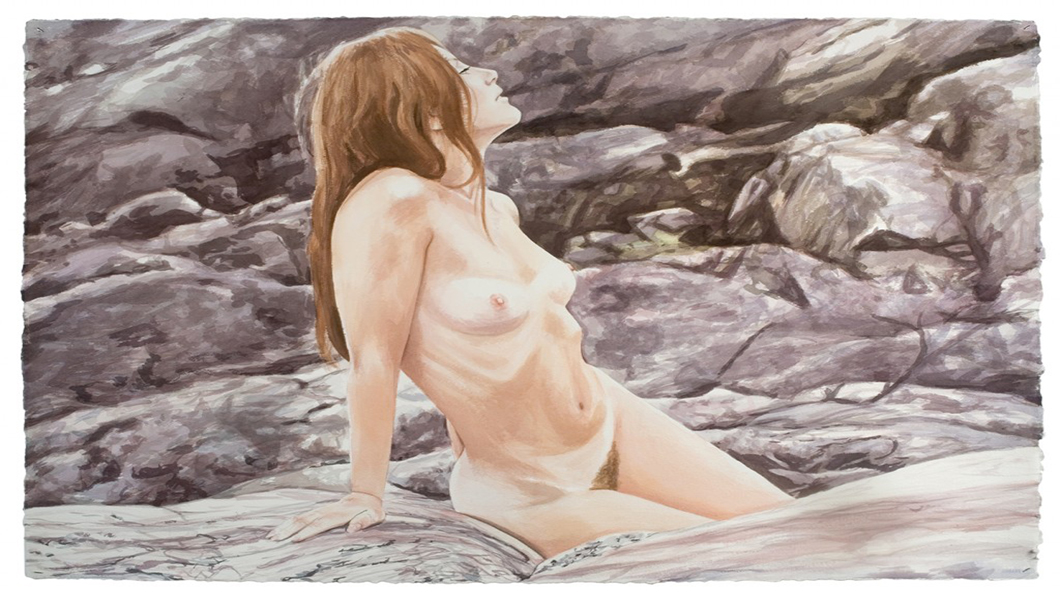

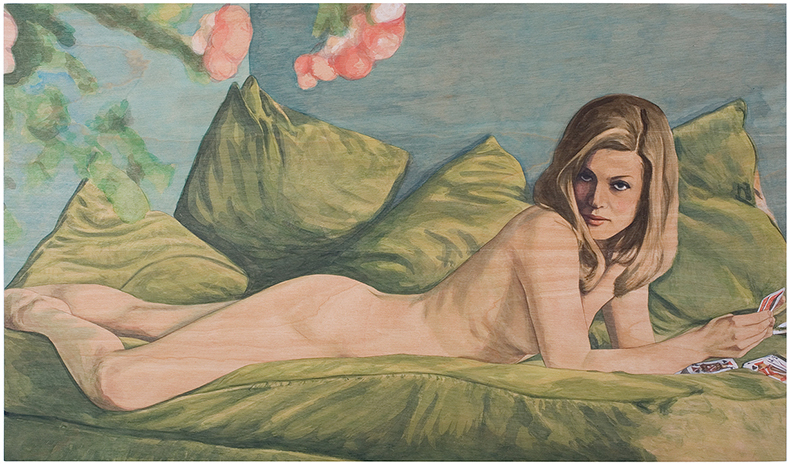

There is a window between the 1960s and 1970s where models in men’s magazines have a naturalness about them— certainly, they are still idealized, but, maybe because the Woodstock, hippie aesthetic had become so widespread, their hair and makeup isn’t overdone, and they capture a certain fantasy of freedom. “In anything from before then,” Sinclair explains, “there’s a little stiffness. And then it’s the 1980s, and things begin to look weird,” overproduced and glitzy instead of earthy. So all her subjects come from that window. Because she works deliberately and with only as much paint as necessary—“I’m definitely a planner,” she says— her images, whether on wood panel or paper, have a quality that recalls the smooth, easy surface of a magazine image.

She began using old books, fashion magazines and vintage pin-ups as sources while a student at Massachusetts College of Art in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Drawing from already-made imagery dug up in the library was a way to portray people without the pressures of working from a live model. Then a friend’s dad decided to get rid of his lifelong Playboy collection and the friend bequeathed the magazines to Sinclair. “She gave me bags and bags and bags of them,” the artist recalls. “I think at first I treated them like collector’s objects. Then I started tearing out the pages.” Her earlier paintings have a more linear, straightforward quality. They recall the spare images of Alex Katz, for instance, in which deliberate lines are used to convey every detail. More recent paintings have softer edges and a bit more nuance.

Sinclair is not entirely sure why this particular aesthetic compels her, except that it may have something to do with nostalgia for a time she just missed. “Generations are always fascinated with the generation right before,” she says. People have an urge to excavate and then maybe romanticize the era that produced them.

She is often asked about the “erotic” in her work, a word she hates, even though she understands its relevance. “I’m not unaware of my source material and how I’m choosing to use it,” she says, although, especially now that she’s moved to rural Maine, away from city life and art world distractions, she’s thought more about those issues that might underlie her choice of these particular figures. “When I go into the studio, it’s like I lay down on my analyst’s couch and wonder, Why am I doing this?”

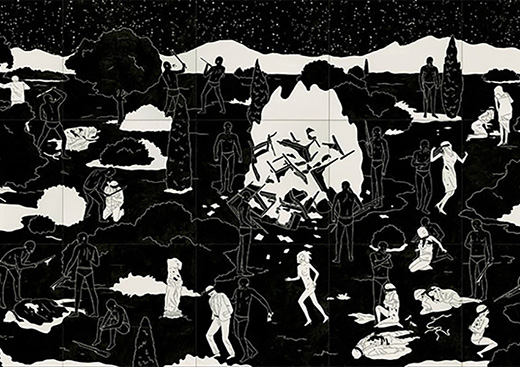

Around 2008, after the seminal WACK! exhibition on feminist art debuted at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Sinclair remembers seeing the sprawling 1972 collage “Hothouse or Harem” by artist Martha Rosler. It is a sea of nudes, all from the 1960s and 1970s, cut out from magazines like those Sinclair uses. “I remember standing physically in front of it and saying, ‘I know all of their names.’”

She has become intimately familiar with these models’ careers and identities. Yet they are also types, posing in proscribed ways, one looking a lot like another. This contradiction may in fact be Sinclair’s real subject. In her renderings, like the one of flaxen haired Carolyn, who looks like she’s straight out of the cast of Sofia Coppola’s Virgin Suicides , the spark of personality is undeniable. So is the familiar style and posed nature of the image.

“A lot of what I do is in a way trying to explore painting as self-expression, self-portraiture,” says Sinclair. She doesn’t at all mean that her portraits are actually of her. Rather, they explore that question of how the specific desires and affinities of a person, like her interest in these women from men’s magazines of eras past, mesh with bigger realities. How do you express individuality while still acknowledging the ways in which you conform to a social type? There’s no easy answer, which is probably why Sinclair’s project continues.

—