IT’S BEEN OVER 2 DECADES SINCE ’93 AND SOULS OF MISCHIEF IS STILL CHILLIN’.

If you were to step inside a serious hip-hop head’s exclusive record vault, you’d likely find Souls of Mischief’s 93 ’til Infinity on precious wax, possibly framed. The Oakland-based group’s debut studio album was and still is a flawless work of audible art that never ceases to appear on best-of lists, making it an integral part of the groundbreaking genre’s history. And while the pioneering foursome and lifelong friends have heavily influenced both the independent and mainstream hip-hop arenas for more than two decades, they’ve miraculously managed to dodge the manipulation of commercialization, allowing them to live in this infinite sweet spot that merges street accreditation with global appreciation.

Formed in the Bay Area in 1991, Souls of Mischief features four members of the equally influential hip-hop crew, Hieroglyphics: Tajai, A-Plus, Phesto and Opio. Prior to rhyming with their core collective, the killer quartet met when they were just pint-sized talents. East Oakland native Tajai Massey (Tajai) and Colorado expat Adam Carter (A-Plus) were already spitting in grade school at the ripe age of 8. Tajai recruited his best friend Damani Thompson (Phesto) in middle school and A-Plus brought Opio Lindsey (Opio) into the budding act in high school.

Just two years after hitting the scene, SoM scooped up a major label deal with Jive Records and released the aforementioned 93 ’til Infinity in 1993. Equipped with unforgettable tracks like “Never No More,” “That’s When Ya Lost” and the title single, “93 ’til Infinity,” the funk-infused album was an underground success, offering true beat junkies a refreshingly unique sound that was unlike anything being produced by more established hip-hop acts during that time. Rather than take the easy route of excessively gabbing about babes, blunts and bling, SoM’s perspective challenges the listener to think, offering a provocative array of memorable lyrics, both bold (“Puns and phrases I stun in phases”) and brainy (“Shins get split, men get spindled, swiveled, pivoted by my riveting centrifuge”). Their distinctive approach to the genre garnered a myriad of accolades, including a spot on The Source’s 100 Best Rap Albums list.

Twenty-one years after releasing their groundbreaking chart- topper, the life-long friends now have six studio albums under their belt, including No Man’s Land (1995), Focus (1999), Trilogy: Conjlict, Climax, Resolution (2000), Montezuma’s Revenge (2009), and the recently released anniversary joint There Is Only Now (2014). Produced by eclectic hitmaker Adrian Younge (he’s worked with everyone from Ghostface Killah for “Twelve Reasons to Die” to Jay-Z for “Picasso Baby”), the live instrument-heavy production is a clever nod to the group’s ’90s roots, offering nostalgic, storytelling sounds backed by real-life experiences and guest appearances from the likes of Snoop Dogg, Busta Rhymes, Ali Shaheed Muhammad of A Tribe Called Quest, William Hart of The Delfonics and Scarub of Living Legends. There Is Only Now proves that there’s no better time to remind the hip-hop game that Souls of Mischief paved the way.

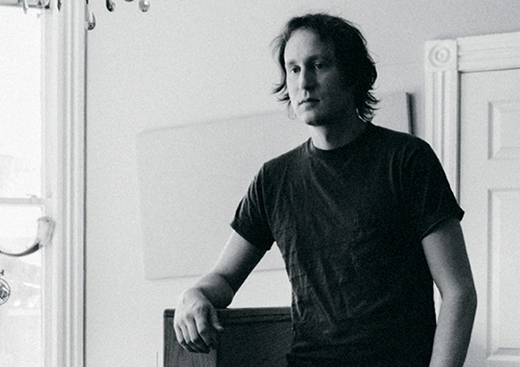

A-PLUS

Similar to childhood friend Tajai, Adam Carter (aka A-Plus) was a brainiac in school, dabbling in both computers and comic books while enthusiastically taking on advanced classes and exploring the then-budding world of underground hip-hop. The spawn of a musical family (his 13-year-old son is starting to make beats, too), the Colorado-born, Oakland-raised talent has released three solo records: My Last Good Deed (2007), Pepper Spray (2011) and the just-dropped Molly’s Dirty Water, which A-Plus calls “an EDM- inspired hip-hop album.”

“I’ve been into EDM [electronic dance music] for a long, long time,” A-Plus explains. “I just want to see if I can do a hip-hop hybrid. So I’m just pushing my boundaries. I’m always trying to inspire myself to do different things, push my envelope further. A lot of early ’80s music was completely electronic. I’ve been to a lot of raves, done a lot of psychedelic shit. In the mid-2000s I was dating a chick that was into that stuff a lot, like all the sub-genres of electronic music. I was listening to it more and more, and I guess around 2009-2010 I was really trying to start learning.” Those Souls of Mischief kids, always learning.

On the subject of throwbacks, A-Plus recalls the days when technology and hip-hop were separate entities, allowing the genre to maintain monetary value on an organic level. “At that time, you know, before P2P and file sharing and Napster came into play and all of that, independent hip-hop for us was extremely lucrative because we kind of cut out the middleman and we still

had an audience,” he explains. “So all we had to do was make sure we had a distribution deal, and once we got that we were able to make all the money that the record companies could make off all of our audience. For example, getting a couple hundred thousand on a tour would be considered a complete failure, but selling a couple hundred thousand as an independent—as a group, not on TV and not on the radio—is so fuckin’ money.”

Instead of blowing hard-earned cash on the flash that today’s rappers tirelessly boast about, A-Plus and the rest of the Hieroglyphics made a smart splurge: “Around 2003, we took the money and invested it and bought a big-ass warehouse out in East Oakland to hold our studios,” he notes. In addition to hosting the group’s offices and shirt-printing business, the approximately 8,000-square- foot compound, known as the “Hiero Compound” or “Hiero HQ,” is also where There Is Only Now was recorded. (About the album’s name: “We were in the midst of making the album and we hadn’t come up with a name yet,” A-Plus says. “Then, Tajai said the lyric ‘There is only now’ and everybody was, like, ‘Shit, yeah.’”) While Tajai can take credit for the album’s title, it was A-Plus who made initial contact with producer Adrian Younge: “I emailed him and said, ‘Dude, you want to work with us? We want to work with you!’ And he was like, ‘Hell yeah, let’s make this shit happen.’ After that, we talked about it for, like, five or six hours. I talked to the rest of the crew […] and a couple of weeks after that we were in the studio.”

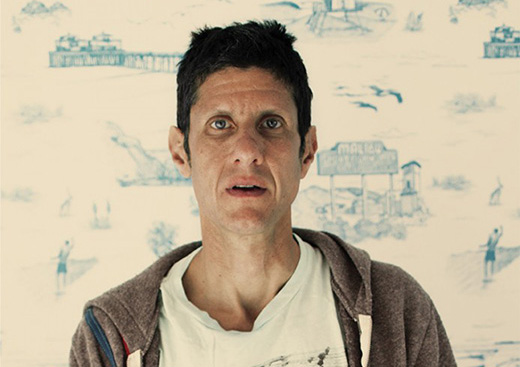

OPIO

Two driving forces behind Souls of Mischief’s success are education and friendship. Similar to Tajai and A-Plus, the multi-talented Opio Lindsey thanks his upbringing for instilling his skills. “I think it was our parents, you know?” he adds. (His father was an attorney who represented the likes of Richard Pryor and Ice Cube.) “Education was always the most important thing in my home—and the same in everybody else’s home. It wasn’t, like, a scenario where you can just be lazy and shit. We had a thirst for knowledge that wasn’t just about being in class—it was just kind of this natural connection we had with each other.”

Opio—who has released a handful of solo works, including Triangulation Station (2005), Vulture’s Wisdom, Volume 1 (2008) and Red X Tapes with Equipto (2011), and recently worked with SoCal underground hip-hop producer Free the Robots—explains that the group’s thirst for knowledge is also why they naturally entered the hip-hop game early on. “We are fans, fans that are lucky enough to do music,” he adds. “We have a passion for hiphop music and culture. “I was writing graffiti, breakdancing and DJing; we all tried everything. That passion and love for the music kind of connected us during a time when it wasn’t really cool to be a rapper. You know, people would be like ‘You a rapper?’ and think it’s funny and shit. Nobody was a rapper; in America there were probably 1,000 rappers at the time. So that kind of made us have a strong bond. [People would try to make] hip-hop be this negative force or some shit like that, like it encourages you to do criminal acts and act thug or whatever, but that’s not it.” He also adds that money was never a motivating factor: “It wasn’t something that we put all this focus on. We were friends first and then hip-hop was just part of our lives and what we did, so it felt natural to do it together—we weren’t trying to get rich off of it.”

While money has never been a driving force for Opio and his Souls of Mischief counterparts, maintaining street cred is a constant stimulus. “We just wanted to put out a record to have the respect of all these emcees that we grew up on and loved,” he explains. “That was more of our focus—to get respect from the hip-hop community. For us, we always try to do something that nobody is doing in hip-hop. We don’t say, ‘Oh, what’s popular in rap music right now so let’s make sure we do that. You know what I mean? That’s always been our biggest strive; we love to be creative but we want to separate ourselves from everybody.”

SoM’s interest in innovation dates all the way back to the ’90s, when the group had its first taste of technology. “I mean, we were basically one of the first websites to do any type of commerce,” Opio reveals. “[Fans] would get in touch with us through our website and then place an order, and then we would mail out CDs and T-shirts and whatever. I think it was around ’96 maybe. I mean, there was nobody really selling anything [online during that time]; we had a website before Chrysler!”

PHESTO

“I grew up in a family of musicians, but I got into music because of my dad and my uncles,” reveals Damani Thompson (aka Phesto or Phesto Dee), rounding out the Souls of Mischief quartet. “My dad wasn’t a real musician—he didn’t play any instruments—but he used to collect a lot of music, so he had records. “That’s kind of how hip-hop started as well, by going through our parents’ records. That was my entry into this world of looking at record covers like Parliament and James Brown, all these people that you hear on the radio. You might have heard them on the radio as a hit but you didn’t know they had this extensive catalog of music. When you were young, you would just hear a hit song but you didn’t know people had all this music and that was where I learned that from, from [my family]. There is another spectrum of music out there that doesn’t necessarily get played in a pop format or whatever. This was before I even knew about hip-hop. I mean, hip-hop existed, but I wasn’t really into it until I started messing with other forms of music first and then I got into hip-hop.”

Once Phesto got into the genre, the genius lyricist went at it full force. Solo projects include Granite Pedigree (2011), Background Check (2012) and the recent Infrared Rum (2014). As far as his work with Souls of Mischief and Hieroglyphics, the new dad (he welcomed a son last year) reveals that he entered the crew when it was just about fully formed. “So, I was watching what they were doing, and [asking myself] ‘How could I fit in without going against the grain?’” he explains. “I mean, how I can bring something new to the group without destroying the dynamic and cohesiveness that already exists? I came from a visual artist mentality because of graffiti. When I first came into the group, I was concerned about the visual stuff because I felt that we had the audio stuff covered. We got dope lyrics, we got dope beats, but maybe visually I can bring something to the table. So that’s why I did the Souls of Mischief logo.”

Phesto’s contribution to the group involves much more than SoM’s memorable emblem. “I feel like my best strength right now is my knowledge of music theory, and hip-hop is really about defying all theories,” he adds. “One thing I learned about music is that it’s one thing to break the rules, but another thing to know the rules in order to break them. So I feel that I’m a person who knows the rules, and that’s why it’s a little different when I break them. When we do need a rule or need something radical from a musical standpoint, I can provide that because I’m kind of trained in a traditional way.”

Speaking of strengths, Phesto adds that the group’s staying power can also be attributed to their support of one another. “I think now we are at the point where we know certain people have certain strengths, and if you are just not as strong in that area, you pick up the slack more in your area. We’ve been friends since kindergarten. I mean, you can’t say that about a lot of people— people who are still good friends and business partners. So it’s not that we have our egos in check, it’s like we knew each other before we even had egos.”

TAJAI

“I went to Stanford for undergrad and got my master’s at Berkeley in architecture,” explains Tajai Massey (known simply as Tajai), one-fourth of Souls of Mischief and one-eighth of Hieroglyphics. Born in Stanford and raised in Oakland, the 39-year-old father of two (“I got a 13-year-old and a 6-year-old”) is the impressive offshoot of a well-educated household (his mom was a professor and dad was “like a sysop or something like that”), setting the tone for SoM’s uniquely intellectual point-of-view.

“I got into computers early on, so I think we were fortunate to have parents that were getting an education, because we were part of the computer and literate community,” he notes. “But it wasn’t like it was an anomaly; you know where we lived.” Indeed, the Bay Area in the ’80s was already a hotbed for tech culture. Because of this, Tajai and fellow group member A-Plus got deep into computer programming at an early age, experimenting with a range of now-classic models, including the Commodore 32, Commodore 64, Apple IIe and Apple IIc. “Tajai was the first person I knew who had the first Mac—the very first Mac!” A-Plus adds.

Just like his advanced computer literacy and burgeoning architecture career (“I just did a cupcake shop for [Hieroglyphics member] Casual’s sister, I did a kitchen for my buddy and I’m working on a container-based mall”), Tajai’s determination to stay ahead of the game is why There Is Only Now is a true envelope-pusher. “We put a lot of effort into this,” he says. “We’re trying to change music a few times, you know what I’m saying?” One of the record’s prime examples of progression is the fact that it’s a time piece set in 1994, right after the release of 93 ’til Infinity. Prepare to be intrigued by the embedded, real-life story of how the guys were attacked after a show that year. “A guy runs up and pulls his ski mask down and was, like, ‘I ain’t playing with you, get on the ground,’” Tajai says. “But while he’s talking about how he’s going to kill us all, he puts the gun up to [Hieroglyphics producer] Domino’s face, and I’m like, ‘oh shit, Domino’s dead.’ Then the guy chases us around the corner and starts shooting at us. It was a terrible experience; we didn’t understand the gravity of that.” Domino’s life was fortunately spared, but the trauma was enough to leave the group permanently shaken.

“Although we made a record that stimulates that era—that feeling— it is still current,” Tajai explains. “So, it’s not like a throwback record. It represents Souls of Mischief in that time period for this record, like a circular rather than linear thing going on at that moment. I think it’s got a throwback feel without being, like, ‘oh, it’s a comeback record’, or we’re trying to recreate that feeling. We’re just trying to recreate the soul.” And while Tajai may appear as the leader of the pack of this retro-soul resurgence, he’s quick to expound the equality of SoM’s operation. “We just recognize and treat our roles in the group like instruments,” he explains. “Like, you know: bass, drums, keys, guitars. It’s like a jazz quartet, or a punk rock band. A guy’s not gonna get up there by himself [and be an] asshole or a bad-ass.”

—