When Albert Watson shot that iconic photograph of Steve Jobs, the one that appeared on the cover of the maverick innovator’s biography and stayed on his company’s website for a month after his 2011 death, he needed a strategy. He couldn’t ask a personality like that, notoriously headstrong and skeptical, to just stand there.

As the session began, Jobs commented, with some annoyance, on the photographer’s archaic use of film. Why not use digital?

“I don’t feel digital’s quite there yet,” Watson replied.

“’We’ll get there,’” he remembers Jobs saying, a promise that proved true. Already the two men were butting heads over their areas of expertise, and what Watson said next played right into this dynamic.

“You have something in mind but everyone in the room is against you,” Watson said, asking Jobs to imagine himself into that situation and adopt the appropriate pose. Jobs stared intently forward and put his knuckles to his chin, a more aggressive, confident spin on the familiar “I’m thinking” gesture. Watson shot a test Polaroid and then the photograph that has circulated so widely since. Jobs asked to keep the Polaroid. “He said it was the best photo ever taken of him,” Watson recalls.

Fans of the photo, like photographer Levi Sim, who made a series of images inspired by it, have pointed out that the subject’s face and features compel you so completely that you don’t think about who the photographer is, what kind of lights he used or what kind of camera.

This has been among Watson’s strengths almost since the beginning: being stylistically distinct without taking attention away from his subjects.

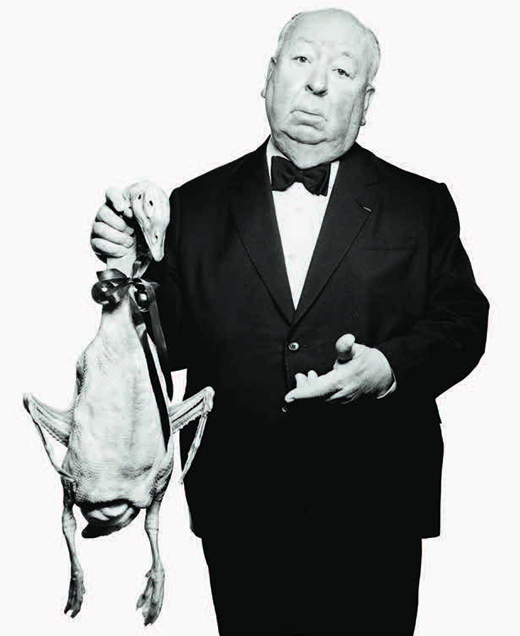

Born and raised near in Southern Scotland, Watson studied graphic design for three years in Dundee before going to film school in London, even he decided in his teens that, at least in some capacity, he wanted to take pictures for the rest of his life. In 1970, he moved to Los Angeles with his wife, Elizabeth, who found a teaching job that could help keep them afloat for a while, and began looking for photography work. He received his first serious assignment in 1973, when Harper’s Bazaar called, looking for someone to photograph Alfred Hitchcock for their Christmas issue. Understandably nervous, Watson devoured Hitchcock’s films in preparation.

The director had shared some goose cooking tips with the magazine, and the editors imagined an image of him standing in an apron with a platter in one hand. This struck the young photographer as needlessly tame. What if this director known for psychological thrillers held the skinned goose by the neck? Wouldn’t that be truer to the Hitchcock ethos?

“Well, you’re sort of strangling it,” Watson told Hitchcock once their session had begun, “and you’re feeling a little bit guilty that you killed this goose, but [y]ou killed it, so what are you going to do?” The goose has a bow around its neck in the finished photo, and Hitchcock’s expression is perfect — slightly regretful but not quite apologetic.

By 1974, Watson had opened one studio in Los Angeles and smaller one in New York. By 1976, he was living fulltime in New York, where ad and fashion work was more plentiful — he had started taking Vogue assignments — and where the industrious, fast-paced feeling better suited his sensibility (“You have to be careful in L.A.,” he says. “It can feel like you’re living in a retirement community.”). Certainly, the success of the Hitchcock photograph and his subsequent work for Harper’s Bazaar helped, but he is not quite sure why his career took off with the speed that it did. “It could be that I was just passionate,” he offers.

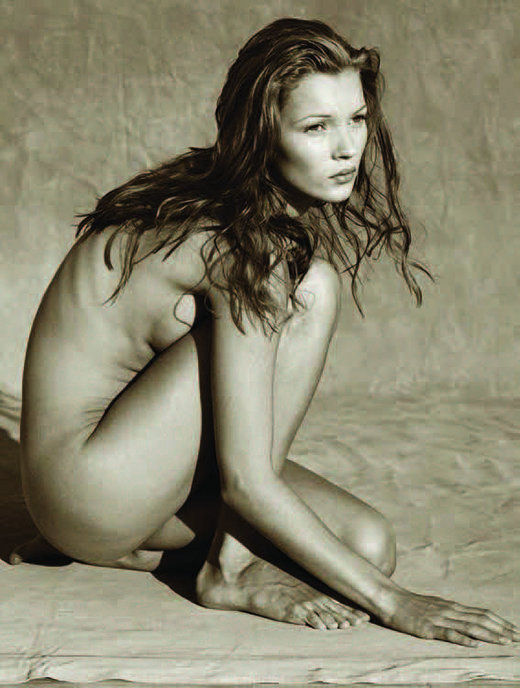

In the 1980s, he photographed Any Warhol wearing binoculars and Grace Jones looking indomitable. In the 1990s, he compiled a book of images of Morocco, photographed Uma Thurman in all yellow for the Kill Billposters and shot his portrait of nude Kate Moss squatting under sunlight. In 2003, he published a book on Las Vegas, a project that had taken root two years earlier, not long after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. He had been in Vegas at 6’clock one evening, and saw a backlit billboard against the sunset. All it said was “GOD” with the red and white stripes of the American flag undulating behind that capitalized block letters. The sky behind it was orange-red and deep blue, seemingly as patriotic as the billboard. Watson always has his camera, and so photographed the scene. “It annoys me if you’re a photographer and you only do fashion or portraits,” he says. “I’m a photographer.” This is true in any situation.

Last winter, he returned to his native Scotland, to do a series of landscape photographs on the Isle of Skye that he plans to exhibit at Milan’s Museum of Modern Art in 2015. BBC filmmakers visited him there, shadowing him and his assistants as they worked. At one point, Watson explained to the camera that he wanted to bring his own style to this exquisite landscape, but it can be difficult to pinpoint what exactly his style is at first.

“Sometimes, photographers are recognized by what they photograph,” he says. Given his range of subjects, this wouldn’t work with him. “But there’s a very easy way to look at all of my work.” He cites the years he spent as a graphic design student before going to film school. “My work is graphics or film-atic or a combination of the two. When you look at everything you can almost drop them into these categories.” The Isle of Skye photographs are cinematic, with their majestically rolling hills and romantically cloudy skies.

His early photograph of Hitchcock had been graphic, a bold figure posed against a clear background. He remembers that, forty years ago, after he finished photographing the director, a secretary brought in two cups of tea on beautiful China. The men talked shop. “’Storyboards are where it’s at,’” Hitchcock told Watson. “’When I’ve done a storyboard, the movie’s finished. All I have to deal with is something spontaneous that might happen. When I have a plan, I follow the plan.’” The then young photographer remembered the advice, but had already begun following it, creating his own storyline for Hitchcock and the goose just like he would years later for Steve Jobs or for the pale skinned models he photographed nude in a pool in 2011, using film over digital to achieve the eerie translucency he wanted. “Now, being a photographer for so long, you tend to do these things naturally,” he says. There’s no need to overthink when he knows what he’s doing.

—