PAOLA KUDACKI: Hello, can you hear me? Hello?

MARIANELA NUÑEZ: Hello.

PAOLA: Hello, can you hear me?

MARIANELA: Yes, I can now. There we go.

PAOLA: Technology … Are you in London?

MARIANELA: Yes, I’m in my dressing room.

PAOLA: Perfect, great. How was it that you decided to dedicate yourself to ballet and become a dancer? Was it your dream, or how did it happen?

MARIANELA: I come from a very traditional Argentinian family, a family that is quite big. I have three siblings; we are four in total. I’m the only female, and I’m the youngest, so that had a lot to do with why I got started in dance.

After having three boys, my mom was up to here with soccer and with boys’ stuff, and, well, she dressed me in pink and put bows on my head, even though I didn’t have any hair when I was little. The first thing she did—as soon as I was able to walk—was to take me to a studio near my house to take dance lessons.

The studio was very small, very neighborhood-like. I come from a neighborhood called San Martín. This studio was three blocks away from my house, and it was in a garage, the teacher’s garage. She kept her cars in there. Basically, the floor had tiles, and there was a ballet bar.

PAOLA: With car oil on the floor? [Laughter.]

MARIANELA: Yes, and we took our lessons there, and they weren’t only ballet lessons. We did a bit of Spanish dancing, a bit of folk dancing. There was a bit of everything. Amongst all that, there were my ballet lessons. I attended along with my kindergarten classmates, but I didn’t like it that they went. They didn’t take it very seriously. It was just a game to them, which is normal for 3-year-old girls. However, I didn’t see it that way; I scolded them every time they lost concentration.

My head made a click right away. I took it very seriously, and then a year and a half or two years after that, I told my mom I don’t want to do the rest, that I only want to focus on ballet, and I’d like to go to a place where they can really do it more seriously and with more commitment.

My mom couldn’t understand at first, but she saw that I was so decided, so she took me to another studio. It was also near my neighborhood of San Martín, but the teacher only focused on ballet. She had studied at the Teatro Colón school, so she had a profound knowledge of dance.

She watched me for a little while and said to my mom that she thought I had talent, so to just leave me to her. I began taking lessons with her, and a year later she suggested I audition for the Teatro Colón school. So that’s what I did. And I got into the Colón at 8 years old. That’s how it all started.

PAOLA: You discovered your passion when you were very little.

MARIANELA: The truth is, I can’t explain to you why. I didn’t have much access to dance; I just fell in love with dance and gave in to it. I still can’t explain it to this day why I love to dance so much. It goes beyond any explanation.

PAOLA: Fate is very crazy, and how it occurred to your mother to take you there and how you said, “Yes, this is it.”

MARIANELA: Exactly. My mom had danced folkloric music, but she never had any contact with classical music. So it’s really inexplicable.

PAOLA: Now, something that sounds so important—and let me know if I’m mistaken or not—in ballet, you have to have a specific body type.

MARIANELA: There isn’t a formula for how it should be, because some dancers—you’ll see we have different bodies, proportions and musculature, so there isn’t a formula. It’s not like there is one body type and that’s it. No, but of course, certain things are fundamental, and they make sure they are there before letting you in at the Colón Theatre or the Paris School. For example, the Royal Ballet School demands you have a physical exam where they check those things. Of course, as your career progresses and if you obviously have a strong body type that is flexible at the same time and supports and helps you not to get injured so much, that’s a privilege.

PAOLA: Because the training is so rigorous?

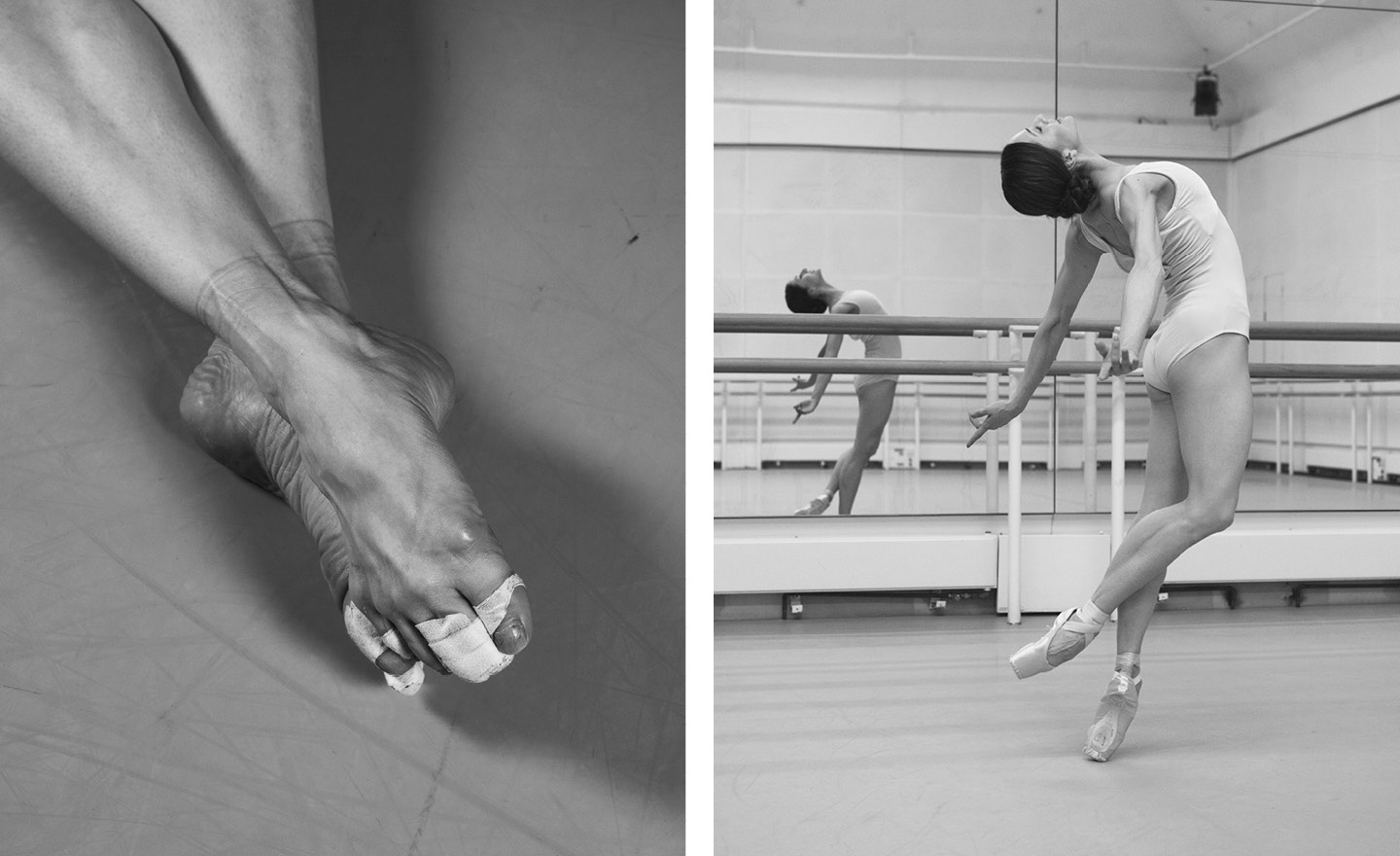

MARIANELA: Right. It’s hours on top of hours of work, and you use your body 100% every day.

PAOLA: Have you encountered any obstacles during your career that gave you any restrictions?

MARIANELA: Not really. I couldn’t really say, “This is truly an obstacle. This was hard. This stopped me.” No. The truth is that I didn’t have any of that. There were things, though. For example, during my teenage years, I did struggle with keeping my body in a shape that I was more or less happy with while being strong at the same time.

I struggled with that. I wanted to find the right balance. I always did it healthily and with lots of people around me, helping me. That was one thing. It wasn’t an obstacle, though; it was a test.

PAOLA: What is your motivation in those difficult times? Even though you haven’t had any specific obstacles, I imagine that, in spite of developing yourself and constantly growing in your career, you always have ups and downs. As human beings, we aren’t perfect.

MARIANELA: Being an artist, you are constantly looking to outdo yourself and improve. I don’t like to use the word “better” or say, “I want to be better,” because with art, it’s not really like that. I try using the expression “going deeper.”

PAOLA: Growing.

MARIANELA: Growing artistically. First, I’ve had a career here at the Royal Ballet for 21 years. You have to constantly want to do this everyday year after year. I have it in my soul. The need to go deeper and grow artistically is there every day. Sometimes you feel that you are going somewhere and other times you get a little stuck. That’s how it goes.

PAOLA: Because in order to grow, you need passion to be your engine, right?

MARIANELA: Look, regardless of what happens in my life, I know that I get up at 8 a.m., and I know that I’m going to hold onto that bar. I’m going to get to the ballet studio. Whatever happens, even if I’m going through the worst moment of my life or the best moment of my life, dance is always there to rescue me and hold me up. That’s something I value very much. Dance protects me. I feel supported by it.

PAOLA: When you were just starting out, did you miss anything? Or did you think about living in the moment and were you fascinated with what was happening to you?

MARIANELA: No, I missed my family like crazy during the first years. I even missed my brothers fighting with me at dinner time. I missed it when they changed the channel on the television when I was watching what I wanted to watch. I missed it all. I struggled in the beginning. I missed my mom so much in my first year of school. But it was all worth it.

PAOLA: Would you say that you have realized all your dreams? What are your next dreams?

MARIANELA: You know what? I have realized all my dreams. You know what, though? All of them came true, and others appeared along the way that I was not even aware that I had.

One of my dreams is to have a very long career; I’d like to keep dancing the classics for another 10 to 15 years. I want to keep growing and exploring. I’d like to keep discovering myself as a dancer. I still have the freshness I had when I started—that’s thanks to my love and passion.

PAOLA: What do you love most about your work?

MARIANELA: I couldn’t express it as a single thing. I couldn’t choose one because there are too many ingredients.

PAOLA: What does it feel like when the curtains open and you start dancing in front of a great audience in a big theater?

MARIANELA: Once I put on my ballet shoes, I experience it. What I feel when I dance—it’s inexplicable.

PAOLA: Although you know the repertoire so well and have performed the same ballet for years and years, do you still feel excitement?

MARIANELA: The excitement is there always; it’s there when I dance and when I rehearse. It’s always exciting to me.

PAOLA: How do you prepare yourself mentally and physically? Do you have any type of mental preparation?

MARIANELA: My boyfriend Alejandro is a genius, and he got me started in meditation and mindfulness. Those things have helped me very much. I could be in a dance studio for nine straight hours and you won’t see me disconnected at any moment. I’m there, present. Dance connects me with mindfulness and meditation right away. I can feel that I meditate while I dance.

PAOLA: What you say about mindful meditation, I too discovered it a couple of years ago, and it’s super important because it keeps you connected. I believe that sometimes the body disconnects from the mind, and through meditation, it’s like they unite. Also, acceptance is super important.

MARIANELA: Super important.

PAOLA: Do you think at some point in your career you had a big break, where you noticed that something had changed after that?

MARIANELA: I can’t say, “I did this. This is it. I made it.” Perhaps my big break happened at a given moment, but I didn’t take it that way, not because I didn’t notice it but because I had a different goal.

PAOLA: The journey is the destination.

MARIANELA: Exactly.

PAOLA: Do you ever identify with any of the characters from the ballets you’ve danced?

MARIANELA: In every role that I play, there is a small piece for sure. The fantastic part is how every one of these characters relates to human life, with your life, with things, with human flaws and with weaknesses. The strongest parts of a human being are in every one of those characters—that’s what I like.

PAOLA: I imagine that in your case, it feels like everything was quite organic. Your growth developed in a quite homogeneous way, but I believe that patience is important too. Patience, hard work and persistence.

MARIANELA: I feel very grateful because I’ve always been surrounded by people that helped me constantly. They made me grow day after day and year after year. I felt protected all the time. You grow and you come up with your own ideas and ideals, but you always have to listen no matter what.

PAOLA: Exactly. I believe that in your vision, which is also my vision, when we have a creative job or in any aspect of our lives, really, if we want to keep growing and developing ourselves, we are always going to discover new angles and horizons.

MARIANELA: Absolutely.

PAOLA: It’s kind of like you never make it.

MARIANELA: That’s why I’m thankful to dance for having adopted me. I’m very thankful for my parents for having helped me to discover my passion when they took me to that first ballet lesson. I’m thankful to the Royal Ballet for having adopted me and allowing me to become a part of their family. I’m thankful for how I discovered my passions, my willingness to continue. I am thankful for my curiosity.

PAOLA: Curiosity—there it is.

MARIANELA: That’s what I’m interested in and excites me. There are many little girls attending the shows. They come to see me at the stage door after the show.

It’s about transmitting that message of curiosity, because I believe that the young generation now doesn’t have any access to that. They want everything now and to make the least possible effort. I hope they start to realize that the journey is success. It’s about making that journey.

PAOLA: Now, with the internet and social media and everything being available and at the reach of our hands, our ears and our eyes, the young generations think that success can happen overnight and that they don’t need to work.

MARIANELA: You grow little by little, day after day. That’s what the success is. Day after day, you have to be like, “OK, I put this in. I improved. I achieved this,” but those are personal feelings. It’s like, “OK, it cost me this. I will rehearse this for more hours, and I’m going to put more into this. I’m going to go deeper into it.” That’s already success from a personal aspect.

PAOLA: There is no money that can really compare to the value of passion and being able to do what you really love. You are privileged to have been able to find your passion, because that’s the key to a life of constant growth.

MARIANELA: That’s it!

PAOLA: Marianela, you give me goosebumps. Thank you so much!

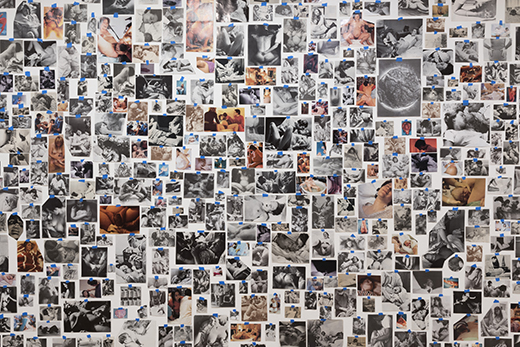

MARIANELA: No, thank you. You gave me goosebumps with the pictures you took of me. [Laughter.]

PAOLA: [Laughter.] OK, dale. Te mando un beso grande.

MARIANELA: Dale. Beso gigante.

PAOLA: Chau, chau.

MARIANELA: Chau, chau.

—