CHARLES MOFFETT: Alright. How are you doing today?

PAT STEIR: Oh, I have terrible back problems every day.

CM: Oh, I’m sorry. Are you still up to chat today or would you like me to try you another time?

PS: No, this is OK.

CM: OK. Well, thank you for taking the time to chat with me today, especially given your back problems.

PS: Oh, thank you.

CM: I don’t want to take up too much of your day, so if you’re OK we’ll just dive right into some questions.

PS: OK.

CM: I’m curious to know what you hope the viewer sees when standing in front of your paintings and this common thread becomes known.

PS: Well, I hope the viewer sees their own heart, not mine. I hope it triggers something in the viewer that the viewer wants to see or needs to see. In other words, I think of it as a trigger. I don’t want to put a message on somebody, I want them to see what they see and find what they find and hopefully it’s a trigger for an inner dialogue with themself, whoever the viewer is and why that would be different, whatever that person’s story is. So I think of art—not only my art but of all art—as a trigger rather than a message.

CM: Along those lines, you once said that through your work you were hoping to reach the soul of other people. Is there a certain audience that you’re trying to reach?

PS: I once said it but I don’t mean that anymore.

CM: That’s interesting. Why is that?

PS: I don’t know why—I guess I’ve changed. In other words, I want the work to trigger what that viewer needs to trigger. Like landscape, when you look at landscape, beautiful landscape, each person gets a set of emotions and thoughts that are not the same as each other person. It comes from their own history and their own background and their own ways of seeing, and so I’d rather it be approached like landscape rather than like a message.

CM: That’s very interesting. I’m fascinated by the idea that the message has changed or it has evolved . . .

PS: It hasn’t changed. I’m old now—I said that when I was young. Everyone changes. I hope everyone changes.

CM: As do I, especially I think in this day and age. I guess along those lines of evolution, and maybe this has changed as well, but referring to abstraction as taking a lifetime to figure out, I’ve noticed your vocabulary around this idea has changed, and now you refer to these paintings as “nonobjective” rather than abstract.

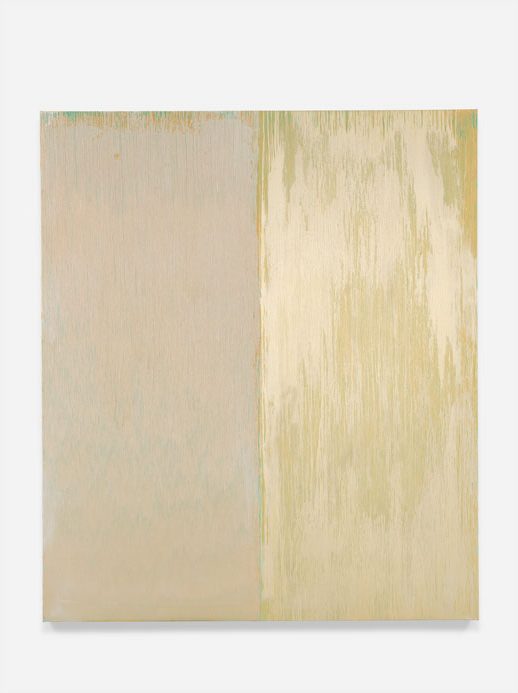

PS: Yeah, because I think of abstraction as abstracting something, but I wanted them to trigger their feelings of landscape but they’re not imitating landscape. They’re not abstractions of landscape. Nonobjective is the best way to call them. In abstracting you abstract something, some figure in some way. I think people call them abstract paintings because that’s the available language.

CM: Is each painting started the same way? How do you start each painting?

PS: They start with the same green underpainting.

CM: And when you first started using the green underpainting, is this a color that you arrived at organically or did you know immediately that this was going to be the best way to push out the color?

PS: Well, I just knew that it would because of what I know about color, that this color would do what I want. It defects everything on top of it through layers and layers of paint, one on top of the other.

CM: I read where you talked about painting as being an object and also a voice, which I thought, especially in today’s political, social and cultural climate that we’re in, is there a voice of your work that may be different now than say in the late ’80s or ’90s, or even two years ago?

PS: The voice always changes, like it does in a person, you know? You read a book and you have additional thoughts or other thoughts or change your mind. So the voice changes. But maybe the voice for me is that right now a lot of young people are making ugly art, purposefully ugly, and they’re reflecting the ugly times we live in. They might not even know it, you know? It might not be an overt political statement, might be just a reflection. Art reflects the moment, and I’m making overtly beautiful paintings, or trying to for sure, and I think as a political gesture to put some beauty into the conversation.

CM: I absolutely agree. I tell a lot of my peers that there’s nothing wrong with beautiful paintings. I think it’s an important thing to add to the conversation, especially in today’s environment. Along those lines, when you taught and lectured, was there a certain message, or did you have some advice for younger emerging artists who are grappling with not only a changing political landscape but also the way that the galleries function today?

PS: Well, I wouldn’t want to be young trying to find a gallery, that’s for sure. There’s so many artists and so many galleries and so many opinions and so many ways to manipulate opinion, it’s really confusing. I’m trying to help a young artist get her work seen, and it’s difficult. My advice is just don’t give up. If it’s really the only thing you can do and the only thing you want to do, don’t give up. But if you’re iffy about it you’d better give it up.

CM: I find the power of experience still to be incredibly important, with seeing work and seeing work in context, which my fear is if we were to see more closings for small and mid-level galleries, we’d run the risk of becoming a totally art-fair-centric culture, yet being able to see everything in context in an exhibition as yours is now I think is wildly important.

PS: I think so too, because how can you know a young artist by one painting or one piece of sculpture, whatever they make, in an art fair? You really can’t. I think everyone under 40—40 and under or even maybe 50 and under—has a hard time. It used to be hard to get into art school, so that weeded out a lot of people who weren’t totally committed.

CM: Where does the work start for you?

PS: Everything begins with a concept. I always say the cat sits on our refrigerator and looks at the door and suddenly jumps up and jumps out the door. He had a concept—he knew he wanted to get on the other side of the door. Anyway, I start with a set of limitations, that is for each painting I would set a limitation.

CM: That’s interesting. What are the limitations?

PS: Limitations are I choose a set of colors to work with and I don’t waver. I don’t madly struggle with the painting and change my mind in the middle and try another color. I just follow what I set out to do. The other limitation is pouring the paint. I pour the paint, the colors that pour the underpainting, and then the wind in the room and the heat in the room and the coldness in the room affects how the painting looks, how the colors are layered, so those are the decisions I make.

CM: In the studio do you move between works or is each canvas a start-to-finish process?

PS: No. I work on a few canvases at the same time, because I work with oil paint; it takes a long time to dry, and if I just worked on one painting at a time it would take me six months to finish a painting because it’s layers of paint and I let the layers dry slowly, so I work on two or three at once.

CM: Given the layering process of your work, I imagine it would be difficult to stop or start over. Is there ever a time where you think I need to stop or shift directions or is each one truly completed?

PS: Each one is completed. If I think it’s not up to par at the end I don’t exhibit it. I save it, though. I save everything. Sometimes I go back to see it and I think why didn’t I want to show this one, and then I show it at a later date.

CM: There’s this one question that I’ve been thinking about quite a bit and maybe the answer’s very straightforward, but since I visited Lévy Gorvy and saw the show [Pat Steir: Kairos], I’ve watched the interview a number of times, and you mention going to visit Agnes Martin out in New Mexico, somebody who became a dear friend. And there’s a part when you’re retelling the story, you mentioned that she asked to see your sketchbook when you saw her.

PS: The first time I visited her, yes.

CM: And if I understand it you said no, and I was just curious to know why you didn’t want her looking at the sketchbook.

PS: I was very young and I had thought they weren’t good enough and I didn’t want her to see something that wasn’t good enough. I was just starting to make paintings.

CM: Did you begin sharing work with her in future visits?

PS: No, but I’ll tell you a story. My first exhibition was at the Philadelphia Museum, the art school there, and right after I had my exhibition Agnes had an exhibition there and Agnes saw my work there and she sent me a postcard. She said your paintings made me feel real good—that made me feel real good.

CM: Well, it’s a beautiful hang and I’m glad I had the opportunity to speak with you. I thank you for taking the time to chat with me for a bit today.

PS: I hope I’ve been helpful … and thank you for such insightful questions.

CM: Well, thank you. That makes me feel good. To be honest I was a bit nervous to get on the phone with you. You’re very accomplished and I’ve long admired your work, so this has been a true pleasure.

—