“IT WAS ALL VERY QUICK. I HEARD VERY LOUD SHOOTING. MY HUSBAND WAS AWAY WORKING. I WAS CONFUSED AND TERRIFIED SO I RAN WITH NOTHING BUT MY BABY IN MY ARMS. WHEN WE ESCAPED TO THE BUSH IT WAS AS IF MY BABY KNEW OUR LIVES DEPENDED ON IT BECAUSE SHE NEVER ONCE CRIED. I HAD NO MILK TO GIVE HER BUT SHE NEVER CRIED.” —A YOUNG CONGOLESE WOMAN ON ARRIVING AT THE UNHCR RECEPTION CENTER IN ANGOLA

“REFUGEES WERE ARRIVING IN TERRIBLE CONDITION, SOME WITH MACHETE INJURIES, MANY HUNGRY, EXHAUSTED AND TRAUMATIZED.” —PHILIPPA CANDLER, REPRESENTATIVE, UNHCR ANGOLA

“VICTIMS ARE THOSE WHO WERE UNABLE TO ESCAPE AND DIED IN THIS ATROCIOUS CONFLICT. REFUGEES ARE SURVIVORS. THEY LOST ALL BUT THEIR LIVES AND THEIR DIGNITY. WE [UNHCR] ARE HERE TO PULL THEM BACK UP AND HELP THEM RECOMMENCE. REFUGEE WOMEN MIRROR THAT INCREDIBLE STRENGTH BETTER THAN MOST. THEIR ABILITY TO ADJUST, KEEP THE FAMILY TOGETHER AND COPE WITH ADVERSITY WITH A SMILE STRIKES ME EVERY TIME. THEY ARE NOT MADE OF STEEL; THEY ARE HUMAN BEINGS MADE OF ALL-HEARTED MUSCLE.” —MARGARIDA LOUREIRO, UNHCR EXTERNAL RELATIONS OFFICER, ANGOLA

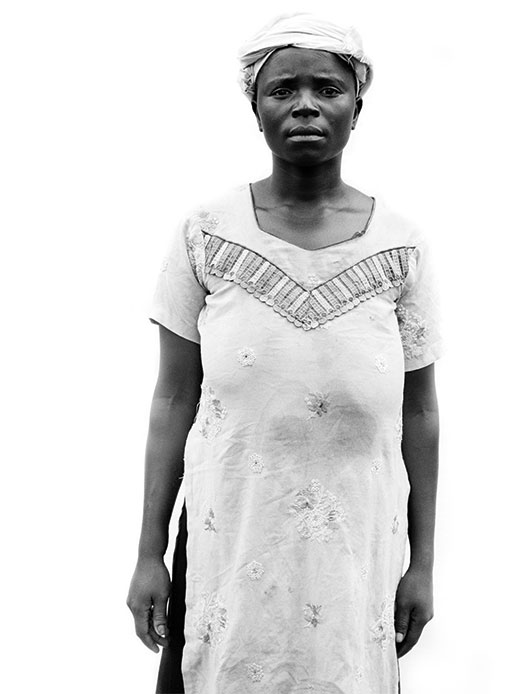

GILI NTUMBA, FROM KAMAKO

In modern conflict, it is often women who carry the greatest burden. Wars no longer have front lines. Civilians are increasingly targeted. Rape and sexual violence continue to be used as weapons of war, and when forced to flee homes, it is women who take charge to hold families together and support children.

The viciousness against women was particularly brutal in the recent outbreak of violence that began in March 2017 in the Kasai region of Democratic Republic of the Congo. It triggered the internal displacement of some 1.4 million persons and the flight of over 34,000 refugees into Lunda Norte Province in northeast Angola. The newly arrived reported widespread violence, mass killings, mutilations, burning of property, destruction of villages, schools and churches and human rights abuses, as well as food shortage and the lack of access to basic services and goods.

Most specifically the refugees arriving in Angola spoke of government forces and militias deliberately targeting women in some of the worst gender-based violence the region has seen. As families fled across the border to neighboring Angola, the medical staff that received them were shocked by the stories and medical condition of many of the women and girls arriving.

Many of the Congolese refugees who arrived in Angola have been relocated to the UNHCR settlement of Lóvua. Currently there are over 9,000 Congolese refugees there, but the settlement has a capacity of 30,000. In Lóvua, 75% of the Congolese living there are women and children. With men often missing, dead or unable to work, it is the women who have to try and rebuild shattered lives and support families.

When I visited the settlement, I was immediately drawn to join three women who sat outside their tent: Rose (who would soon become Aunty Rose to me), her sister Mimi and Bernardette. We sat all day telling stories, laughing and sharing food.

Together we decided to do a series of portraits of just the women, for them to tell the stories. When I returned the next day, the scene was more like a party. No children or men were allowed; food was prepared, new batteries bought for the radio. We danced, we ate and we made portraits. It was truly the most memorable photo shoot of my life, in many ways a celebration, a celebration of life.

Resilience is a word used too easily, but with Aunty Rose and Mimi, and later all the women I met in the camp, I found its true meaning. The women I got to know and visited each day were full of life and joy despite all they had endured, and all radiated a deep strength that rooted their whole families.

Though I am also aware that we must be careful not to romanticize resilience. By its nature, resilience is a necessity born of suffering. It is not a virtue one aspires to, because its journey is hardship and pain. So whilst I admired the strength and resilience of the women I met, it was impossible not to be impacted by the terrible violence that they had witnessed and suffered on that journey. For some, those experiences were still too raw and violent for them to cope with, which is reflected in their words and the eyes of the portraits.

These portraits show the strength of women. But they are also a reminder of the terrible gender-based violence, rape and sexual abuse of women in conflicts around the world.

On the first day, sitting with Rose, Mimi and Bernardette, I asked them how they had endured and survived.

“That’s simple,” was the reply. “We are here because we are strong.”

COCO MAWA, 35, FROM KAMAKO

“Life in the camp is not easy. It is the woman who works, who cooks, who looks after the children. Sometimes when I go into the woods to gather leaves to cook with, I dream of my past life.”

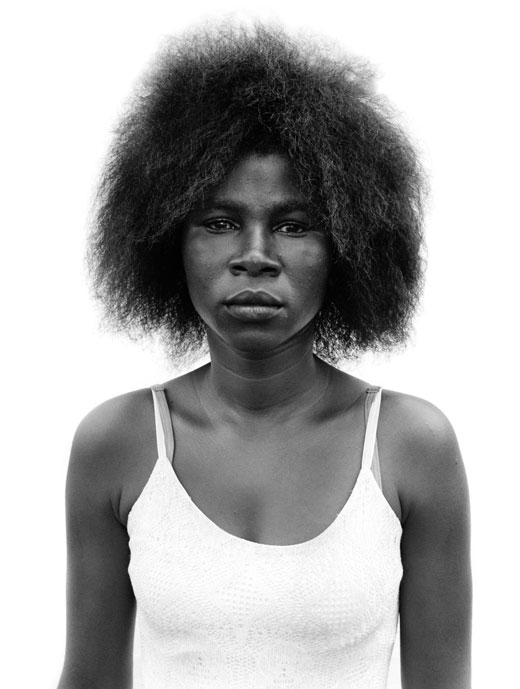

ROSE LUSANDA, 46, FROM KAMAKO

“A woman is a helper. We carry the strength. The women hold the community together,” explains Rose, or Aunty Rose, as she is known. She is in many ways the matriarch of the group. “In the markets, they would charge us more because we were Luba. They would say ‘kill all the Lubas.’ Then when the soldiers came, we escaped. They were killing everybody. Threatening the people, raping our daughters. They were forcing fathers to sleep with their daughters, and if the men refused, they were shot. Being a woman we were stripped of our strength by their threats. Kabila made us suffer.” Then Rose pauses and looks at me as she raises her finger. “But we cannot be weak. We escaped the war. No other human will give you that strength. I had that strength inside of me. I had the courage to do whatever has to be done. Sometimes I say to my daughter, now we are here [in the camp]. I tell her to feel the courage. To find the calm, be calm, stay calm.”

MIMI MISENGA, 45, FROM KAMAKO

“Sometimes I am very sad at all we have lost. Other times we let it go, we have our lives. They killed my uncle, his sons. We couldn’t even bury them. It was too much. My neighbor, they made him rape his daughter. Then the troops raped the daughters in front of the family. I was so afraid for my children. We escaped barefoot into the bush and then found a way to escape. I had nothing. Then I looked at my children. They gave me strength. I am never tired. I am so strong. My body is always moving, ready to work, even when I sleep! Honestly, I don’t know where that strength comes from. I am never tired. I say to my daughters, ‘Stay calm, find a good husband and follow my example. Follow my strength.’ ”

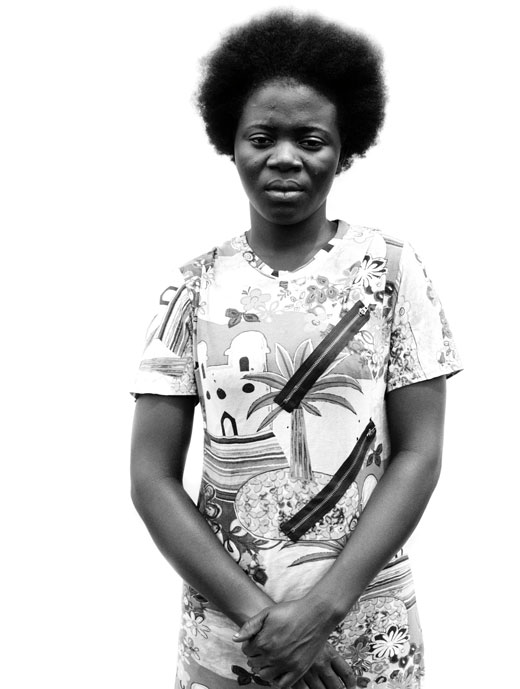

CARINE ROLENGA, 20, FROM KAMAKO

“When we heard gunshots in the village we knew it was time to leave. As a woman I felt particularly under threat. At night they would take the men and rape the women. In truth I don’t understand why people would do this. It’s beyond me.”

MUZI KINGAMBO, 26, FROM KAMAKO

“It is not easy. I suffer here. I have many pains in my back, my bladder—pains women shouldn’t have. In Congo I lived with my husband. I want that life again.”

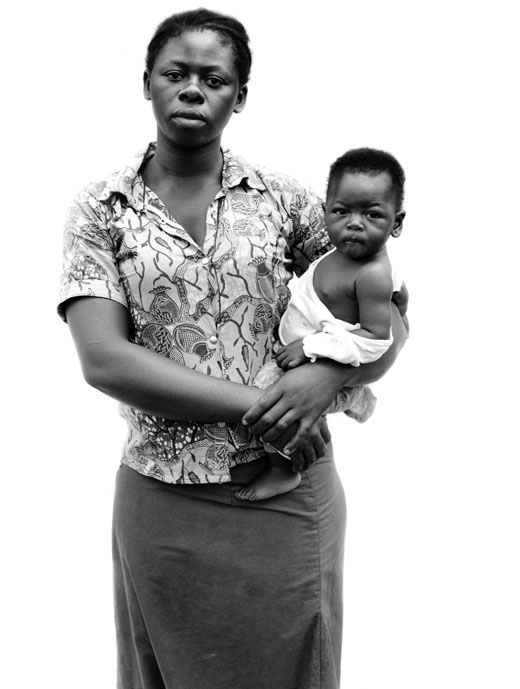

THÉRESE MANDAKA, 19, FROM KAMAKO

“Here we suffer a lot. For us women, we were particular targets. The biggest suffering was kept for us. When the soldiers came, I was separated from my husband. He’d gone to look for work; I was home and sick. I was pregnant. But my strength comes from my home. Even though I was sick, I knew I would have to escape. I thought they would kill the baby inside me—that’s where I found my strength, nobody else but me. “Now here in the camp I am a mother, so I must be strong.” Thérese pauses and gathers herself. She has not seen her husband since she fled to Angola. He hasn’t seen their child, Munduko, who’s now 4 months old. “I just want us to be together again.”

ANI TCHEBA, 19, FROM KAMAKO

“We left our village in Congo on a Monday morning at 6 a.m. I remember I had no strength. I was heavily pregnant. It had been a difficult pregnancy and I was so worried I’d lose the baby. My husband pulled me. As a refugee it is harder as a woman, as we have the responsibility for food and the children. But here the women have given me inspiration. We share food. When I am missing something they give it to me and vice versa. We help each other with the hardships. We are stronger together.”

GERMAINE ALONDE, 25, FROM KAMAKO

“We had good land at home, a good life. Then the militias and the armies came. They took everything. They killed my older brother. It was terrible. We saw so much blood, and each time my heart would stop. I couldn’t sleep. Then one day they came near to our home to start their killing and we all fled. We were terrified; everyone was running. We knew what they would do. My oldest daughter, Therese [who was 7], took my baby Helene [who was just 2 years old] whilst I ran back to the home to gather what I could and get the other children. At the border everybody was pushing and shoving. It was chaos. I couldn’t see Therese; we were all separated. And in that chaos she dropped the baby. We lost her. It was the worst moment, but I couldn’t be angry with Therese. How could I be? My oldest child is just a child. It wasn’t her fault. For two weeks we thought Helene was lost. Then one day in the camp my neighbor came up to me and said she’d seen my baby. I couldn’t believe her! But she had-—she’d been walking past a center for unaccompanied children and she’d seen Helene! We went straight away and were reunited. There was so much joy.”

SYLVIE KAPENGA, 26, FROM TCHISSENGUE

“Being a woman and a man is the same. They were killing us all the same. Where we were we caught between two sides. Everybody wanted us to die. I have four children, two girls and two boys. It’s tough here—little food, no clothes, just what we have. As a woman, I am the one that works. To be honest, I am not that strong. I lost everything. I am not sure how to carry on.”

BERNADETTE TCHANDA, 42, FROM KAMAKO

“I ran from Kabila’s war [Joseph Kabila, president of DR Congo]. We saw the troops come. They killed many people. They pointed a gun at my husband, but we managed to escape with our two children. As a woman I was particularly afraid. The sounds of weapons, the sound of death. I was afraid. The troops would rape, they would kill women. This happened to my friends. I feel protected here, in the camp. In the past, my husband would beat me, but not here, they have laws and he is scared. I have a lot of joy…” At this point Bernardette breaks from the interview and begins to dance. “I get a lot of strength when I dance. Women get strength from dance.” She stops dancing for a moment and looks at me. “Women suffer the most, so they have the most strength.”

LINA MANANGA, 18, FROM KAMAKO

“Here,” she tells me, pointing at the camp around her, “each day we wake in the morning, we collect water, we clean clothes, we look for what we can eat, we cook. This is our day. It is tough, physical work. When we fled Kamako, I remember the day; the children were dressed in red when the troops started arriving. As soon as they arrived they started shooting, cutting people’s heads. I was repulsed. As a woman I felt in a lot of danger. I was with child and I knew that even if I gave birth that day, they would kill the child. I have seen this. I have one child. Because of this violence, I had a miscarriage with the other. I am young, so I have to be strong. But some are not.”

CHANTAL KUTUMBUKA, 45, FROM KAMAKO

“I used to be a farmer. I’m used to working with my hands. So it’s hard for me to be here. I just want to work. We had land, we could sell things. I could look after my children. When the violence started I lived in fear. The militia would go to a house and I would see them carry out the woman. I knew what they were doing. I was afraid—I couldn’t have endured that. Then one day they killed my husband, who was a policeman, and we fled. We abandoned everything. It’s hard. I’ve lost weight, the children cry. At times I don’t know what to do. But I carry on.”

—