In May 2001, Margaret Kilgallen approached the 30-foot interior walls of the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia with buckets of recycled house paint, and without the aid of guides or stencils trusted her hand and instinct to spell out the phrase “Main Drag” in carnivalesque letters nearly three stories tall. Along the base of her oversized lettering, Kilgallen hung small paintings on salvaged panels and stitched-together canvases. Each added element extended further across the museum’s walls, until illustrations and words were clustered edge-to-edge and Kilgallen’s hand-painted lettering spilled into the open space of the museum and onto shacks built of reclaimed wood. By the time Kilgallen had completed the installation, “Main Drag” was an immersive survey of the artist’s prolific body of work. It was a tribute to her heroines, an homage to her community and a celebration of the myriad subcultures from which she drew inspiration.

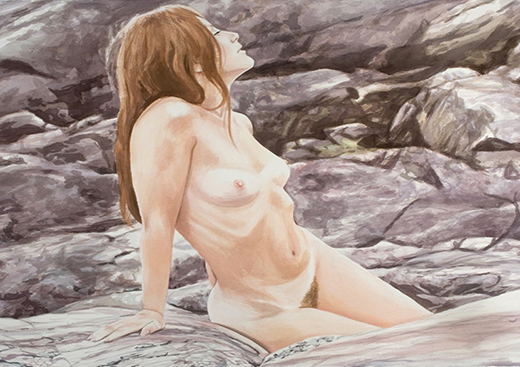

Through the installation, Kilgallen depicted a world that combined surf culture, old-time music, hobo graffiti, the coastal landscape, the signage that adorned her neighborhood and illustrations of women at work and play. Each image and phrase was personal and specific almost to the point of being esoteric, yet each felt essential and interconnected. “Main Drag” was the swan song of an artist whose impact and legacy is greater than the sum of her artworks and exhibitions; Kilgallen passed away later that year at the age of 33.

Born in Washington, D.C., Kilgallen studied art and printmaking at Colorado College and moved to San Francisco in the early 1990s, where she would come to prominence as part of a group of artists dubbed the Mission School, after San Francisco’s Mission neighborhood, which included Barry McGee, Alicia McCarthy and Chris Johanson, among others, who all shared a handmade and intuitive approach to art-making. Like her peers, Kilgallen was incredibly resourceful; she was an optimist open to the world around her, finding beauty in discarded panels and paper and gathering knowledge from the disparate traditions of sign painting, printmaking and book restoration. She was deliberate in her pursuit of an eclectic array of techniques and influences.

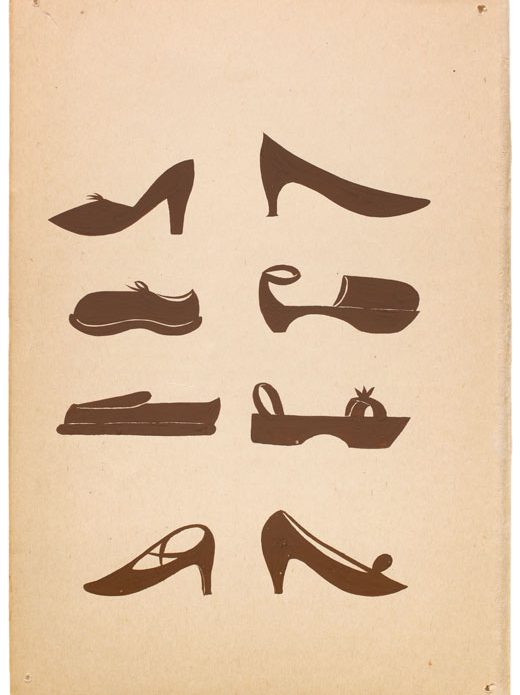

Soon after arriving in the Bay Area, Kilgallen found work repairing books at the San Francisco Public Library, where she learned the arts of bookbinding and paper restoration under the tutelage of Dan Flanagan, a conservator whom she would later cite as a primary mentor. Through this apprenticeship, Kilgallen cultivated the skills and knowledge that could have made for a career in conservation had she not instead chosen to apply her skills to her studio practice. The artworks she made reflected her training: Discarded endpapers became grounds for drawings and paintings, and her canvases were frequently stitched together like the spine of a book. Kilgallen developed a profound appreciation for the character and quality of objects made and restored by hand. She saw potential in the weathered surfaces of old books and paper, and she often sought to reproduce those textures in her artworks, intentionally burnishing her brushstrokes and sanding the edges of her paintings.

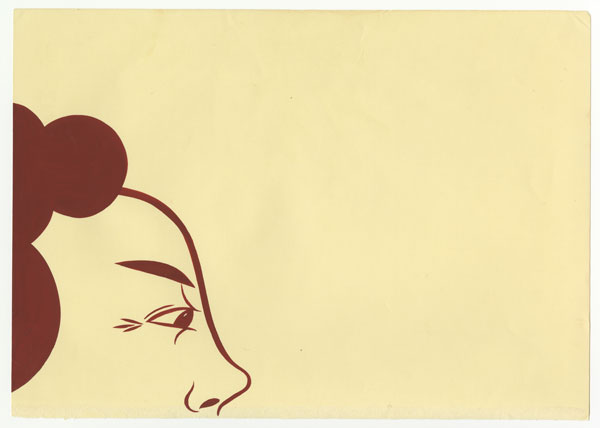

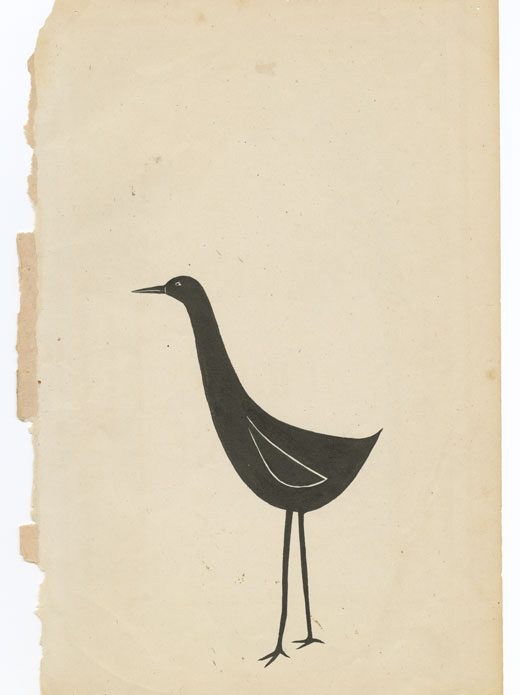

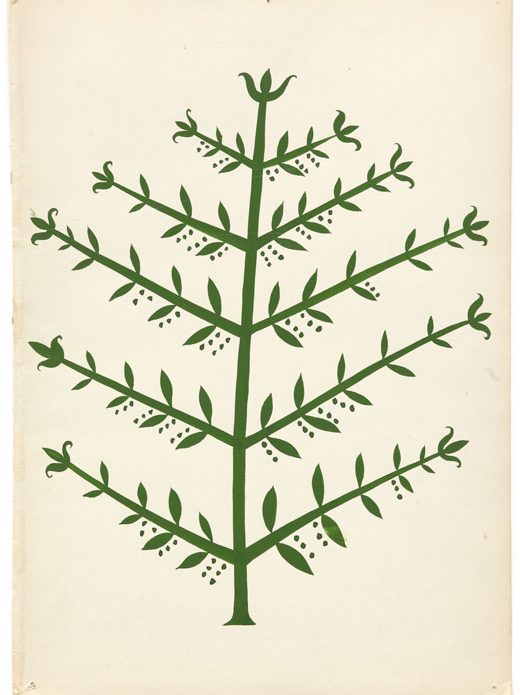

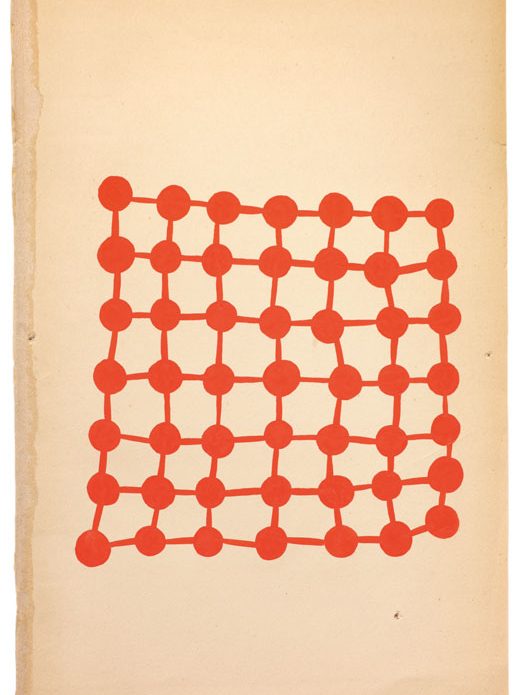

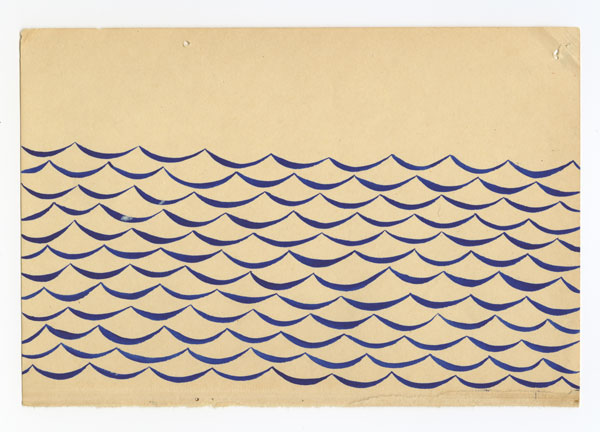

With the library archive as a resource, Kilgallen absorbed as much information as she could about typography and hand lettering. Building on her background in printmaking, she became particularly fascinated by the works of Japanese woodblock printers and painters like Hokusai. She admired the economy and elegance of their techniques; a single brushstroke could become a tree or drapery as readily as it might form a character or word. She sought to constantly perfect her hand and develop her own visual language, where foliage, figures, letters or even a fragmented letter were given equal visual weight. Kilgallen’s works began to use words for both their forms and their meanings. Throughout her artworks, words and letters feature prominently, as a centerpiece in “Main Drag” or as one of many phrases that take on new meanings when repeated from one artwork to the next. Even the artist’s illustrations of trees and plants occasionally bear the marks of ligatures and serifs taken from letterforms.

Kilgallen’s fascination with lettering extended from poster typefaces to the casual typography of the hand-painted business signs from her neighborhood. The unschooled and intuitive quality of these letters found their way into Kilgallen’s drawings and murals, spelling out phrases and names like “Linda Mar” and “Lowers”, which refer to her favorite surf spots along the California coastline, or terms like “Drop Knee” and “Kooks”, which come from the jargon of surf culture itself.

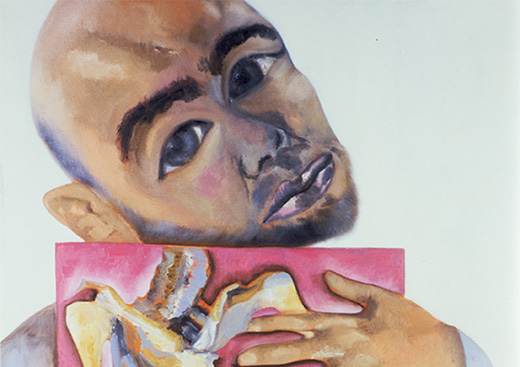

Among the most iconic elements of Kilgallen’s work are the monikers and images that stand in for her heroines, each of whom were characters from underappreciated subcultures, women whose achievements occurred on the margins of the mainstream. The name Fanny appears periodically in Kilgallen’s artworks, referring to Fanny Durack, an Olympic champion swimmer from the early 20th century.

A banjo player herself, Kilgallen had a special adoration for Matokie Slaughter, a pioneering banjo picker of the 1930s and 1940s, and a fellow artist who followed her own path despite the ubiquitous difficulty women face to be recognized as artists. “Slaughter”, “Matokie” or simply M.S. became monikers of sorts for Kilgallen; writing on walls, canvases and train cars, she used the name to evoke folk heroines and elaborate on a legend of her own making.

For Kilgallen, taking her hand from paper to panel to murals to massive installations and out into the world onto the walls of buildings and trains was a natural progression. For her it was all part of the same gesture. She trained her hand to capture the world around her, and left her hand out in the world. As with any attempt to know our heroines, no profile, interview or artwork seems quite adequate to capture her contribution, but each piece suggests a similar story: Margaret Kilgallen was an idealist, intuitist, inventor and in all likelihood, a genius. A generation of artists, writers, designers and craftspeople feel her absence poignantly and her influence pervasively; each painting, drawing or print that survives her tragically short yet meteoric career is imbued with ardor and stitched together with her inimitable hand.

—