Miss Van is a twin, but unlike inseparable street painter peers Os Gemeos or How and Nosm, she and her sister weren’t a lifelong team. “I was always the shy one, drawing all the time,” Miss Van says, “and she was more social, talking with people.” As teens, she and her sister moved away from one another to lead separate lives. “People compared us all the time—we were ‘the twins’ all the time,” she recalls. “I really needed to have my own identity. I started to paint in the street at this moment when I split up with my sister, when I was 17.” Rebellion, pink hair and graffiti with friends in her hometown of Toulouse, France, followed. By 1993, she began to paint female figures in acrylic paint, gradually isolating them from other graffiti as stand-alone works. By the late 1990s, her painterly, brushed “poupées,” or “dolls,” gained notoriety, and spotting new poupées each week became a game for Toulouse residents, even drawing the ire of feminist groups who found her fleshy, pouting characters unsettling.

Moving four hours from her hometown to the then-graffiti paradise of Barcelona in 2003, Miss Van arrived just in time to catch its last era as a relative free-for-all. “I fell in love with the city because of the graffiti, but also because of the light, the sun, the people—I don’t know, everything.” In terms of painting in the street, things were possible in Barcelona that weren’t elsewhere— perhaps particularly so for the striking French woman painting images with a broader appeal than spray-painted graffiti lettering. “Every Sunday, I was painting somewhere—just choosing a place and painting—that’s why it was really different, and I managed to paint a lot this way, just improvising.” But it wouldn’t last: the historic center of the city, a classic locale for camera-toting tourists to catch photos of the blossoming street art scene, became the site of a crackdown. Street painters were forced to the city outskirts, and Miss Van could no longer improvise in the center. “There were a lot of people traveling to Barcelona just for graffiti,” she states of the newly clean Barcelona. “So it’s really a pity that they cleaned all the city, it takes away a lot from here.”

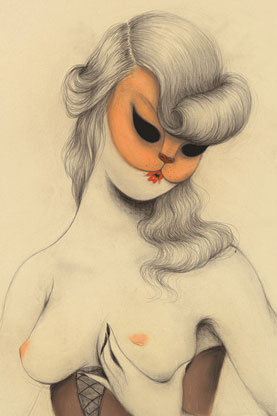

The crackdown changed Miss Van’s trajectory as well. “I stopped painting the street art, I wasn’t motivated to go out of the city to paint, and slowly starting to work more in the studio.” Those studio works found international success in galleries, and expanded into delicate media unsuitable for the streets. Her painting style, which needed to be clear and graphical in the street, grew looser, with just a few marks indicating the folds of a dress or an outstretched arm. Themes and tones changed as well. While her street works were often cheerful and cartoon-like, her gallery works grew darker and moodier, including full shows of girls drawn with their eyes closed, or with grotesque touches like smeared lipstick. “My work was always quite commercial, but not because I decided it but because it was attractive and feminine in the graffiti world. I have a dark side that I need to express also. I don’t want to just make a nice figure; it’s boring. I really like to go though some periods of time and see every show that I did and how my work evolved from one state to another. It’s still the same girl, but in so many ways, and now I’m more dark.”

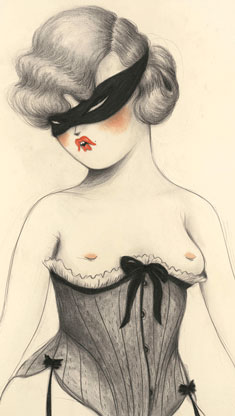

Miss Van’s characters went from plump and pouting girls to anthropomorphic figures in masks. “I was working a lot with a masks,” she says, “and I was hiding my face, because I’ve been working solo for almost 20 years, and it’s hard sometimes to renew yourself and to find another identity and to have another vision.”

This progression and reinvention had to take place within the structure of an instantly recognizable career’s worth of work. “I wanted to find another way to show familiarity,” Miss Van states, “to hide, and mix it with an animal mask. I’m always with this duality of familiarity, delicacy and then the more bestial thing that we all have.” Yet throughout these changes, Miss Van keeps her work consistent—perhaps in no way more obvious than only painting females. “I think it’s because painting girls helps me to know myself better,” she explains. “It’s a relationship between me and my painting—we grew up together. There is always a really thin line between us. It’s my sensitivity, what I like or what I feel or the way I want to show something. It comes from me so it has to be related to me. Every girl can see themself in my painting.”

—

RETURN TO THE HOME PAGE

VISIT CITIZENSOFHUMANITY.COM