“When you are so lucky to do in your life what you like, it means you have freedom,” says Franca Sozzani, whose long wavy blond hair and strong features make her look sympathetic and commanding at the same time. “I probably didn’t know that I was a free person when I was very young,” she says. “I realized in the years, working. And I did only what I liked.”

Sozzani has been Vogue Italia’s editor-in-chief since 1988, the year she turned 38 and the same year Anna Wintour took over at American Vogue. Then, photographers like Bruce Weber, Mario Sorrenti and Steven Mesiel were finding their footings and the faces of Cindy Crawford and Linda Evangelista were becoming synonymous with the seemingly off-the-cuff, grungier glamour of the late 1980s and early 1990s. Sozzani had worked at the children’s fashion magazine Vogue Bambini and at the fashion magazine Lei before arriving at Vogue Italia, and she meant from the beginning for that magazine, which had previously focused mainly on Italian designers, to have international appeal. She succeeded almost immediately.

If you look back at her first covers–a colorful one of an orange-haired model and the severe one all shades of brown, where the model glares back at the viewer–it’s hard to place them in the 1980s. They look more in step with the ethereal, edgy fashion imagery that took hold a few years later, when waif-like Kate Moss was the girl of the moment.

Conde Nast, the publisher of all international versions of Vogue, describes Vogue Italia as the “most influential Italian fashion and style magazine,” “always a pioneer,” setting “the pace of the fashion world” and taking on “topics that are powerful, contemporary and cutting-edge, with an unmistakable style.” Paris Vogue, in contrast, is less floridly described as a universally recognized… key source of inspiration,” and UK Vogue is called “pre-eminent.”

Part of what distinguishes Vogue Italia from other fashion magazines is its overwhelming reliance on images–often, covers will only have the magazine’s title and the name of the month on them, none of that brand of copy meant to grab your eye in a supermarket checkout line.

“The Italian language is spoken only in Italy,” says Sozzani, explaining her overwhelmingly visual approach, “and I thought that if I wanted to be [heard], or even better seen, worldwide, I had only [one] way: To invent a new language.” Even when the photo essay was the main editorial approach of magazines like Life and Vu, words played essential roles: they still shaped readers’ understanding of the cultural or political stories being told. In Sozzani’s magazine, pictures had to communicate everything to the reader; fashion spreads had to be initially gripping and then provocative enough to propel readers through the pages. “The images can talk to you instantly without words or any explications.”

Sozzani has an instinct for finding image-makers, and is committed to the best of those she finds. “I love to meet different kinds of people. I learn every day from everybody,” she says. But learning from people is not the same as choosing collaborators. “You become friends [with people] because you love them, not because they are inspiring or useful. In choosing people with whom I work I want, of course, talented people who can help e. What does it mean, ‘talented’?” Sozzani adds. “Creative and intelligent and ready to change their mind.”

Since the first issue she helmed, Steve Meisel, a photographer who began his career as an illustrator in the 1970s and never privileges prettiness over precariousness, has photographed every cover. “It’s been the most creative outlet that I have,” Meisel has said of Vogue Italia, to which he has also contributed some of the most memorable features. In 1992, for the cover, he photographed Madonna barefoot in the street, in a newsboy cap and trench coat open enough to show a bra, heavy belt and black pants. She’s unsmiling, looking suspiciously at the camera. The accompanying spread inside the magazine showed the pop star as a chameleon. In each photos–some black and white, others in color–she channels an entirely different version of headstrong femininity: she’s a gypsy, a mystic, a sultry belly dancer, a tough-girl rock star and a fur-wearing royal.

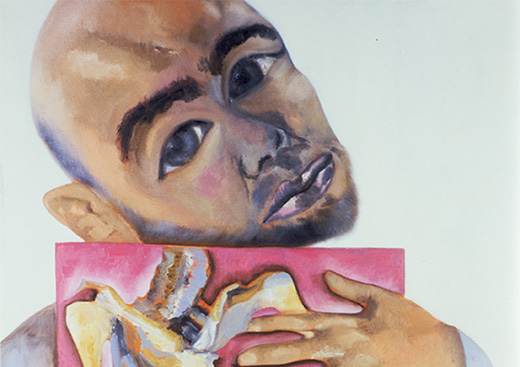

Just over 20 years later, in 2005, he photographed Makeover Madness, a feature in which model Linda Evangelista went under the knife, wearing evening gowns and fur coats while in surgery. Dimly lit and half-noir, half-documentary, Meisel’s images had that combination of grit and otherworldliness that particularly characterizes the work he’s done over the last decade.

Features like Makeover Madness have prompted criticism, partly because they don’t usually take a clear ethical position. Instead, they use glamour to complicate an issue: What does it say about the beauty machine to see a figure like Linda Evangelista with bandages around her face, or with bloody scalpels surrounding her? Why is it so squirm inducing?

“I didn’t choose to please everybody,” Sozzani says of her work at Vogue Italia. “I said since the beginning, ‘Vogue is for many people, not for everyone.’ ” The editor–who uses Twitter and blogs almost daily about the places she visits, art she sees and causes she supports, always with optimistic urgency–says she feels no need to hold back or to muffle editorial choices. She may even aim for more extreme content in the future. “I still have time,” she says.

—