In May 2014, producer/rapper/entrepreneur Dr. Dre pulled off a deal for the ages when he sold his Beats Electronics headphone company to Apple—the most valuable company on the planet—for an astounding $3 billion. In March 2015, Kendrick Lamar, a 27-year-old self-taught musician from Compton, California, released his album To Pimp a Butterfly on Spotify, the world’s most popular music-streaming service. By the end of the day, it had been played a record-breaking 9.6 million times.

Dre and Lamar, two African American men of humble origins, had ascended to the top of the mountain. Their means of transportation: hip-hop. And the man who made all of that possible: Russell Simmons.

That’s not an exaggeration. “Uncle Rush,” as he is affectionately known, created the blueprint—not just for how to commercialize a musical art form that was created by a bunch of inner-city kids who couldn’t afford actual instruments, but also how to manifest its culture. If Simmons hadn’t figured out how to show mainstream America the magical powers of hip-hop, Kendrick might not have ever uttered a verse, because the artists he idolized wouldn’t have gotten on the radio.

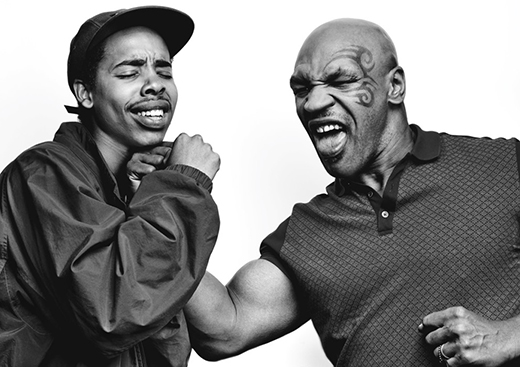

Simmons grew up working-class in Queens, with parents who worked for the city and a pair of artist brothers (one of them, Joseph, went on to become the Run in Run-DMC), but he wasn’t a creator himself. What Simmons had was taste and the courage of his convictions. Soon after discovering New York’s underground hip-hop scene in the late 1970s, he dropped out of college and started promoting parties.

In the early ’80s, Simmons hooked with up with an NYU student named Rick Rubin and together they founded Def Jam Recordings. Their first single: 1984’s “I Need a Beat,” a raw, aggressive track from a 16-year-old rapper from Queens who called himself LL Cool J. The track took off and the rest was music history. Over the next four years, Simmons and Rubin introduced the world to LL, the Beastie Boys, Run-DMC, Rakim and Public Enemy. In 1986, Def Jam exploded hip-hop’s glass ceiling with the release of Run-DMC’s cover of Aerosmith’s “Walk This Way.” What started out as a call-and-response DJ-based party music in housing projects was now a mainstream platform for a generation to express themselves and, if they had the goods, to make a living doing so.

Simmons’s success as a young man provided him with both the resources and the stature to launch what has become his second career: activism. And while his interests span the cultural and ideological spectrum, from health and wellness to animal cruelty and LGBT awareness, Simmons has devoted the majority of his time to causes affecting African Americans, most notably reform of New York’s draconian Rockefeller drug laws and the Black Lives Matter movement.

“As I’ve gotten older I realized that giving without any expectation is the greatest form of giving. It’s also the thing that promotes the most happiness in me,” says Simmons, whose Twitter feed is a constantly updated stream of calls to action for political and social awareness. Simmons’s understanding of celebrity as an agent of change extends well beyond himself, as he spends a considerable amount of time enlisting friends and young entertainers, making them accountable and showing them the power and change they can affect. “This may sound funny, but Khloe Kardashian’s Instagram post for the Black Lives Matter was really part of the reason why 100,000 people were out that day for that rally, which was the turning point that pushed the governor to change his oversight policy on the police department. Pressure makes a diamond, and it’s important this younger generation understands that.”

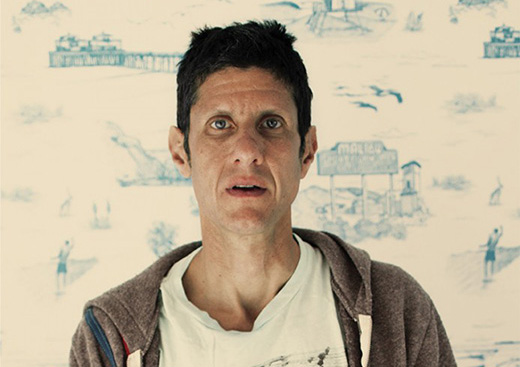

Now 58 and the healthiest he’s ever been thanks to his devotion to yoga and veganism, Russell Simmons doesn’t seem to have lost a beat on the somewhat manic, hyperfunctional energy that pushed him to break down doors his entire career. “Retirement is not in my DNA,” says the mogul. “It’s the furthest thing from my mind. For me, my interests evolve, but the basic idea of being a good servant and doing something meaningful, what that means changes some as I get older, and that’s why I keep serving. I do want to make movies, however. I would like to green-light movies and not have to ask people who don’t understand cultural nuances for permission. All in time, though.”

—