EVER CURIOUS ABOUT WHERE MUSICAL GENIUS IS CREATED? IN THE CASE OF BOB MARLEY’S “I SHOT THE SHERIFF” IT WAS ON A BEACH IN JAMAICA WITH HIS BEST FRIEND, LEE JAFFE.

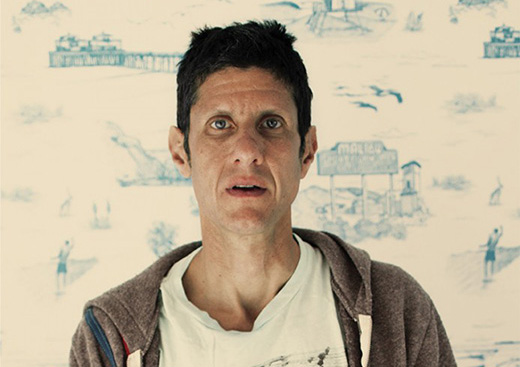

New York City, 1973. Lee Jaffe, a nice Jewish boy from the Bronx with a nose for trouble, was in a tight spot. It wasn’t anything he couldn’t handle. Just an experimental film that was falling apart—not like the Brazilian jail he’d had to survive in without getting sliced, not the stress moving truckloads of weed across the country. But while Jaffe had made his bones—and some serious cash—hustling weed and LSD all over the world, he was, first and foremost, an artist—and a savvy one at that. At just 23, he’d already seen his work, which ranged from conceptual performance pieces to multimedia paintings, included in two landmark exhibitions: “Projects: Pier 18” for the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and “From Body to Earth” in Rio, a collaboration with his good friend, the influential Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica.

But now Jaffe’s latest project, a movie that he’d spent months working on and sunk all of his savings into, had just gone up in smoke, when his producer—and his money—mysteriously vanished in Chile, most likely thanks to a run-in with dictator Augusto Pinochet’s death squad. And now Jaffe was pissed off, anxious, and in need of a new creative trip. He didn’t function well when he wasn’t inspired.

And on that night, when he entered the New York hotel room of his musician pal Jim Capaldi, the founder and drummer of the British band Traffic, Jaffe stumbled upon his destiny. In the room with Capaldi was a soft-spoken Jamaican man of mixed- race ancestry who had just started growing out his dreadlocks. He was holding a cassette tape; a guitar sat on the floor next to him. “Lee, this is Bob—Bob Marley,” said Capaldi. “You should really listen to his record.”

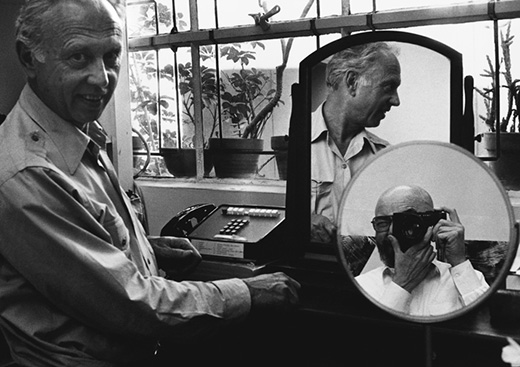

As fate would have it, Jaffe had recently returned from a few months in London, where he’d been turned on to a new and absolutely mesmerizing musical art form that was still unknown in the U.S. One night, a Jamaican actress and model friend had called to tell him to be at her flat at 7 p.m. sharp—they were going to a movie. Jaffe arrived to find Esther waiting for him in a Firebird convertible with Island Records founder Chris Blackwell, a white Jamaican based in London who’d just expanded his reach into film producing. Off they went to Brixton to attend the premiere of The Harder They Come, director Perry Henzel’s portrait of Jamaican gangster “rude boy” culture. The music that provided its soundtrack was reggae, an offshoot of the country’s ska/rocksteady genres that was still in its early stages. Starring Trenchtown reggae god Jimmy Cliff, the film was a game-changer. “I was the only white American person in the audience,” recalls Jaffe. “I didn’t know anything about Jamaican culture. Zero. Nothing. No one knew what reggae was. And I’m sitting there in this crowd of Jamaicans and there were no subtitles, and I was mesmerized.”

And now, back in the U.S. just a few months later, Jaffe was face to face with the man who would soon eclipse Cliff as the heart, soul and face of reggae music. Marley put his cassette in the boom box and pressed play. It was “Concrete Jungle,” track #1 from Catch a Fire, The Wailers’ most recent record. “I’d never heard anything like that. I had absolutely no doubt that what Bob was doing would change the world. For Jamaicans, the Wailers were already the voice of the people, but outside of that world no one knew they existed. Except me.” Jaffe, who had made a habit of trusting his instincts, then seeing his hunches pay off, knew then and there that sticking around the skinny young Jamaican who had come to the states to buy equipment for an upcoming tour would be his next big move. All he had to do was convince Marley that bringing a white guy with no professional musical experience into his inner circle would be a good idea.

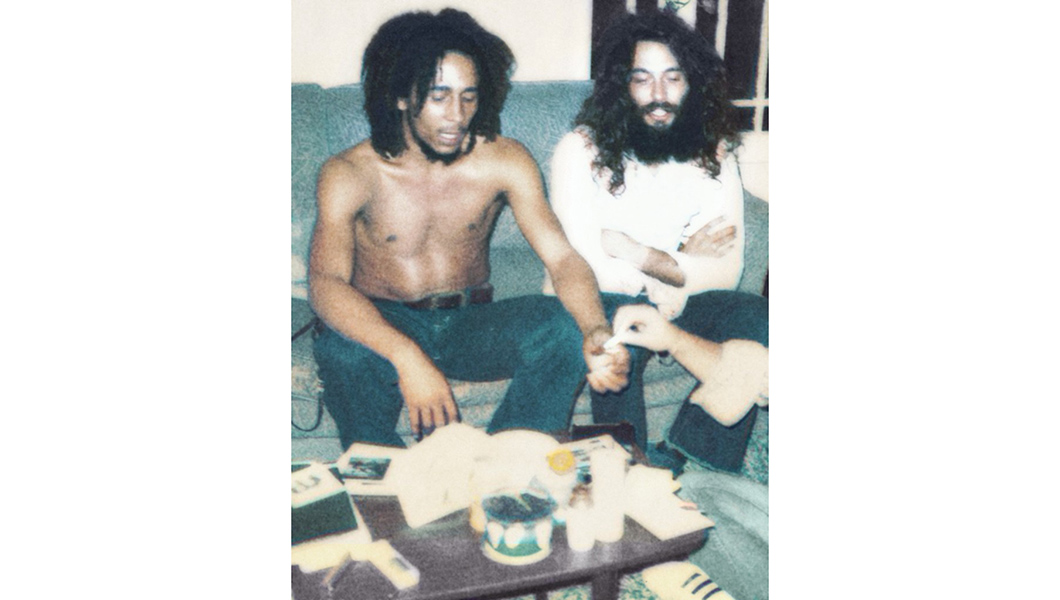

Jaffe had a few cards up his sleeves when it came to winning Marley over. He began by connecting with him in a common language. Jaffe pulled out his harmonica, asking if he was in the mood to play. Marley agreed and picked up his guitar, and the two men began to jam. Jaffe skills were legit—he’d played harp in a few bands before dropping out of Penn State—and Marley was impressed. So far, so good. Next up: providing the devout Rastafarian convert with some spiritual relief. Jaffe took Marley to a buddy’s place on the Upper West Side. “My closest friends from college had become the biggest herb dealers in New York,” says Jaffe. “So I take him to this apartment and there was like 700 lbs. of herb filling up this apartment. It was Columbian, the best you could get anywhere. Bob was really, really impressed. We bonded over that for sure.”

To seal the deal, Jaffe played cupid and set up Bob with his Jamaican friend, who happened to be in New York with Chris Blackwell. She and Bob hit it off romantically. (Marley would eventually become one of the world’s most notorious lotharios, whose conquests ranged from European supermodels to a young, pre- Vogue Anna Wintour.) But they also had other friends in common that made their coupling good for business. In the months since Jaffe had attended the Harder They Come premiere, Jimmy Cliff

—who was looking to cash in on his impending stardom—had left Blackwell’s Island Records label for a deal at A&M Records. Blackwell had known of Marley and the Wailers—whose socially conscious songs had already made them heroes among Jamaica’s poor—but he felt that reggae was still too obscure an art form to warrant his having more than one act on his label. But when Cliff flew the coop, Blackwell needed a replacement, and in stepped Bob Marley & the Wailers.

“It’s just a crazy coincidence,” says Jaffe. “I was maybe the only American guy who knew anything about reggae or had any idea that Island Records was about to bring reggae to the rest of the world. And here I am, hanging out with Bob Marley, this genius nobody knows about yet, who Island had just signed to be their only reggae act. The tape Bob played me, Catch a Fire, was actually his first upcoming release for Island. And the next day I’m introducing him to this gorgeous Jamaican girl who happens to be in New York with her best friend, who happens to be the owner of his new label.”

Needless to say, Jaffe was in. A few days after that first hotel jam session, Jaffe was on a plane to Jamaica, with an invitation from Marley to join him and a few friends for a trip to Carnival in Trinidad aboard Blackwell’s DC3 jet. Jaffe had a blast, and everyone, especially Bob, was taken by Lee’s seemingly effortless ability to blend in despite the obvious cultural difference. “I also brought this amazing Brazilian girl with me,” Jaffe says with a wry smile, “but that’s another story.”

Once Carnival ended and the group flew back to Jamaica, Jaffe says, “I just didn’t know what I was going to do with my life.” Then Marley invited him up to the house that Blackwell had just bought as Island’s home base in Jamaican, and he decided to hold off on buying a return flight back to New York. The two men drove to 56 Hope Road in Kingston, just down the street from the Prime Minister’s house. Neither he nor Bob knew it yet, but that sprawling estate—later known only as “Hope Road,” would become perhaps the most symbolically important piece of real estate in the history of reggae (and the future site of the Bob Marley Museum).

“Behind this old colonial house was this shack, the former slave quarters, and they had turned it into a little rehearsal room,” says Jaffe. “So I walk in, and there were the Wailers. Peter [Tosh] is there with Bunny [Wailer] and they’re playing the song ‘400 Years.’ Then they go into ‘Slave Driver.’ You could feel the vibes, the colonial vibes, the legacy of slavery—just the weight of it. It was amazing. I wanted to stay just because it was this incredible new adventure. I felt this was someplace very, very special—with the most amazing people I’d ever met. Nowhere else on the planet could be more interesting than where I was right then. I didn’t want to leave.”

Jaffe ended up living on Hope Road with Marley for the next three years. With a natural skill set that meshed perfectly with the needs of the music business, Jaffe served as the Wailers’ jack of all trades: road manager, booking agent, publicist, harmonica player (he’s featured on several of the Wailers’ iconic tracks), tour photographer, and of course, herb connect. Occasionally they’d stay at Bob’s wife Rita’s house. It was one night, while watching Jaffe sleep on the floor of Rita’s porch, that Marley was inspired to write the opening lyrics to one of his most iconic songs, “Talking Blues.” “Cold ground was my bed last night, and rock was my pillow, too—that was about me,” Jaffe recalls fondly.

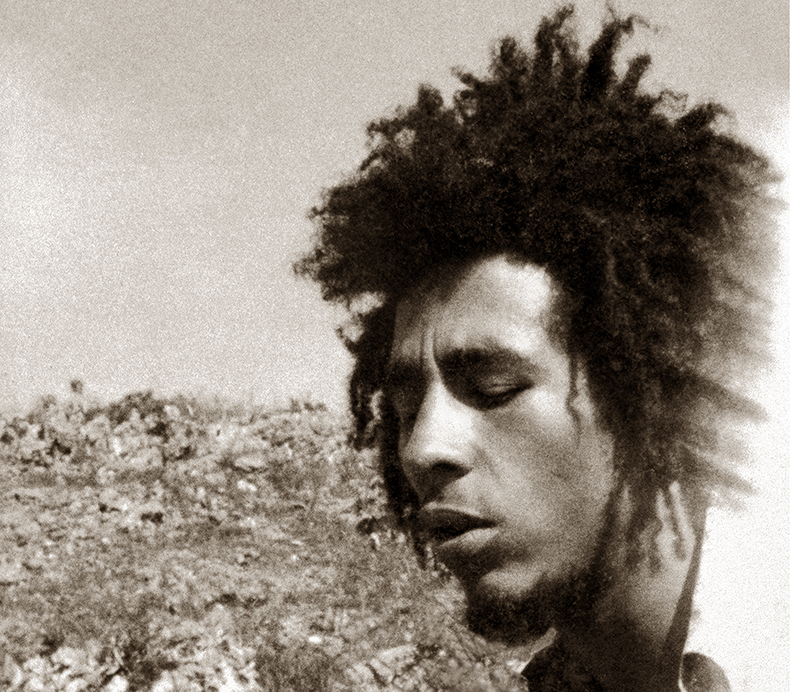

This period, 1973-75, was among the most inspired in Marley’s personal and musical development. The Wailers recorded some of their best early work, including Burnin’, and its lead single, “I Shot the Sheriff,” which catapulted them onto the world stage. Along with maturing as a songwriter, Marley also continued to develop as an activist and cultural figure. For Marley, reggae wasn’t simply an art form—it became a way of life that was profoundly influenced by the Rastafarian principles of social justice and public service—not to mention a devotion to the spiritual and medicinal benefits of marijuana.

Jaffe had no problem putting his own artistic ambitions on the back burner while living in Jamaica. “It was more than being about one person—it was about making a revolution,” he says. “As an artist I felt nothing I could do would make a bigger impact than getting this music out to the world. And there were things I could do to help. I had the privilege of spending time with Marley and playing harmonica while he wrote some of these amazing songs.”

Aside from a rotating cast of musicians, girls, and various hangers-on, the only people who actually lived at Hope Road during that time were Marley, Jaffe, and their two teenage gangster bodyguards, Frauzer and Takelife. “Whenever I was with Bob, no one bothered us,” remembers Jaffe. “But if I went someplace on my own, Bob made those two kids go with me.” (Marley had good reason to be concerned. A year after Jaffe left Jamaica, Bob and his wife Rita were both shot by gunmen during an assassination attempt at Hope Road. In 1987, Tosh and several friends were murdered during a home invasion robbery. Frauzer and Takelife were later killed on the streets of Kingston, after they stopped working for Marley.)

In 1974, Peter and Bunny decided they were ready to pursue their solo careers and left the band on good terms. Marley renamed the band Bob Marley and the Wailers, and continued his ascent to international superstardom. Aside from a six-month-long fight that started when Jaffe and Marley brawled in an L.A. hotel room following an argument over the Natty Dread cover art (a fight that ended when Jaffe got arrested with weed pollen at a roadside checkpoint in Kingston and Marley bailed him out), he was a constant presence at Hope Road.

Jaffe eventually moved out of Hope Road in 1975, following a dust-up with Marley’s new manager. The plan was to move back to New York, but when Peter Tosh played him a few songs he’d just written, Jaffe decided to stick around and try his hand at music producing. The result: Tosh’s classic solo debut, Legalize It, which was financed with $15,000 of seed money from Marley (who appears on the album) as well as the proceeds of Jaffe’s herb business. In typical fashion, Jaffe took on multiple roles to ensure the album’s success, including shooting the cover photograph of Tosh toking on a pipe in a field full of ganja, and securing a deal with Columbia Records.

Jaffe moved back to New York in the late ’70s and continued to produce. He was also a constant presence at Sloan Kettering when Marley, who was diagnosed with cancer in 1977, was receiving treatment there in 1980. Marley had traveled to New York under the radar, following an onstage collapse during a concert in Pittsburgh. Jaffe had a place in Putnam County, and he and Marley decided to take a few days off from treatment and spend a few days in the country. “It was really, really, sad, because he was such a vital person,” says Jaffe. “To me, he was responsible for helping me to transform from someone who didn’t care about living past 30 to really taking care of my body and coming around to a way of thinking that you could live eternally. And then here he was, 7 or 8 years later, and he’s deteriorating right in front of me. On the other hand, I was glad to be with him and support him in any way I could.” Jaffe took Marley to the airport, where he was about to fly to Germany for a round of experimental treatment. “I knew it was going to be the last time I’d see him. His dreadlocks had just fallen out from the chemo, which was a really shocking thing. He was already very, very thin. I got him to laugh about the dreadlocks, which I thought was a great accomplishment.” Marley died six months later in 1981 at a hospital in Miami. He was 36. “Towards the end, there were a lot of people trying to get things from Bob, and I didn’t want to be involved with that,” says Jaffe. “But we spoke every week on the phone. He taught me more about art and music and humility than anyone I’ve ever met.”

For the next 30 years, Jaffe alternated between making his own art and working as a producer and consultant in the music business. He also got back into film, co-producing musical pioneer Tricky’s directorial debut Brown Punk and executive producing the environmental documentary Flow: For Love of Water. Last year, after moving back to New York after nearly 20 years in Los Angeles, he returned to art-making full time with a series of wildly inventive multimedia paintings of the Brazilian rainforest, which incorporate photography, audio and video. In addition, Jaffe will be mounting an installation about boxing at Ireland’s Museum of Modern Art in 2015.

Jaffe, who in 2003 wrote a memoir about his days with Marley, was also prominently featured in Marley, director Kevin MacDonald’s celebrated 2012 documentary biopic, which helped re-introduce the reggae legend to a new generation of international fans and gave Jaffe a chance to relive those magical few years on Hope Road. MacDonald and Jaffe have also begun development on a fictional adaptation of Jaffe’s experience working with Tosh on Legalize It. Jaffe has remained close friends with the Marleys ever since, and occasionally plays harmonica onstage with Bob’s sons Stephen and Julian.

“To experience the music Bob created was just very, very special,” he says. “It didn’t feel as if Bob was even writing the songs. It’s like they were coming from this other magical place, that he was channeling something much greater than himself. To watch it happen, to be there and be part of it, there was nothing I could imagine myself doing at that time that would be more important, more exciting. And it was happening every day.”

—