Lee Clow is responsible for some legendary advertising campaigns—not just effective and popular ones, but ones that penetrated popular culture and changed the game: the Taco Bell Chihuahua, the Energizer Bunny and, along with Steve Hayden, the 1984 Apple commercial that launched the Macintosh computer and the hugely successful “Think Different” slogan. From his lifelong home of Los Angeles, the chairman and global director of media arts at TBWA shared his insights on the ad world then and now.

How did you get into advertising?

I grew up surfing and paying not too much attention in school, but I was always drawing in my notebooks and doodling and taking art classes. I figured that I better make this art thing into a career because I’m not interested in much else. I grew up in California, admired Walt Disney—I’m old, so I was here when Disneyland was built. He was my first kind of artist hero because he was an animator; he did this artful thing, and at the same time made it into a business, and with his passion and his focus, wanted to do great things. So I didn’t know if I wanted to be an animator—did I want to be an illustrator? Did I want to be a fine artist?

The thing that seemed missing in graphic design or just becoming an illustrator was the totality of having ideas and storytelling. As I studied in school it was right at the middle ’60s, when advertising was taking on a whole new status or stature. The intelligent advertising that was being done in New York by [Doyle Dane Bernbach]. The Volkswagen campaign—taking the ugly little car designed by Adolf Hitler and making it interesting, famous and popular. Somehow that really appealed to me. The idea of putting something out into the culture that the public responded to.

What was the first campaign you worked on?

I got my biggest and most important opportunity when I got hired at Chiat\Day, a young creative agency. The first really important assignment brand I worked on was Honda. The account got in trouble after we had it a couple years; they were growing and getting bigger and they kind of challenged the agency to add people and treat them with a little more respect. And we were kind of a cocky, arrogant group and maybe didn’t appreciate the potential and opportunity we had, and now all of a sudden they say, “We’re going to talk to another agency.” Unfortunately we lost the account. So it was kind of frustrating, but that was the big opportunity I had with a big brand, and I also learned some lessons about managing and dealing with the client and understanding the reality of being an applied artist.

Has your approach toward the client changed over the years?

Having an idea is one thing. Showing it is probably just as important, and so I think I always had the passion and the artistic design skills. The storytelling sense came along, and I don’t think that’s changed a lot at all, because I just got more and more passionate and intense—almost in a perfectionist zone. I try to make my work smart, special and relevant.

But learning how to convince clients, convince people on how good and how special an idea is and guarding it is kind of what your life is in terms of all of the pitfalls, all of the ways an idea can be lost. I think being an advocate for my work is the reason why I’m still around when there are a lot of young, talented people I came up with that are long since out of the business. I’m still there because I can nurture young people to develop great ideas and I can help them sell them. I can help them see the light of day, even though it’s getting harder and harder in this kind of new media world we live in with all the constituents you need to deal with.

Traditionally, it seemed like advertising was always about a specific product, but you kind of shifted it to make it about the brand. How did that idea come to you?

The advertising I like to do is to find the brand story and figure out how to tell [it]. You go back to Volkswagen: Here’s a car designed by Adolf Hitler in World War II, and the challenge was to sell it in a country where we were buying cars 30 feet long with giant fins on them and there’s this dopey little car. That was exciting to see that potential, not just to do the individual ads for a brand like Volkswagen but to give it a story that became infectious—that driving a VW became almost a status symbol of a kind of young, free-thinking, spirited people.

Finding a voice as a tone for a brand is the art of what I do. I want to consider myself now as a media artist, not an advertising person, because advertising is kind of defined these days and has a negative stigma attached to it. But to be a media artist is to take a brand and find its voice and tell its story and make it interesting and likeable. I think brands are very much like a person. If you can create a personality for a brand that deals with it like a person and not just a one-dimensional entity—sometimes you’re funny, sometimes you’re smart, sometimes you’re thoughtful. Selling who they are and not just what they make is the exciting dimension of doing what I do, I think.

How was the 1984 Apple campaign created?

Well, of course the most important, being-in-the-right-time aspect of my career was meeting Steve Jobs when he was 25 years old and decides that he’s going to change the world with this thing called a personal computer, which nobody knew what it was, why they needed one, how it fits into their life.

So Macintosh, although we were working on Apple products for a while, was trying to come up with a voice for technology nobody knew they needed or knew why. Steve had this computer that was going to change everything, and he wanted advertising that was as big and important and smart as his product was.

The headline [of a newspaper ad] was “Why 1984 won’t be like 1984,” and it was offering the generic [thought] that says someday everybody is going to have technology—it’s just not going to be for the big companies having this giant computer in their basement. “Someday everyone is going to have a computer” was the spirit of that ad, but it never ran as a newspaper ad.

I was sitting with an art director and another director-turned-writer and we remembered that headline and that just started images in our head—the Orwell of 1984, the Big Brother that kind of controlled everyone’s lives versus the liberator Apple who’s going to take on Big Brother and democratize this thing called technology and give it to everyone. So it just painted this story in our minds, started small and it got bigger and bigger, and we found Ridley Scott, who had done Blade Runner, to give it a stature and style that was not typical of advertising at that moment. And we built it and grew it and it got bigger. [This all] with the promise that Apple was going to change the way the world works, and we called it the democratization of technology. So we have this amazing commercial and were going to run it on the Super Bowl and the board of directors of Apple got cold feet and almost didn’t run it all.

Why did they get cold feet?

Oh, because they were scared of it—it didn’t show the product, it didn’t demonstrate how it worked, although there was a whole ad campaign that went with this commercial, and IBM was coming into the business and threatening them. But luckily we had Steve Jobs, who was one of the bravest businesspeople I’ve ever known, who basically finally drew the lines: “We’re going today.” And it ran and it became pretty famous, and it did put the stake in the ground.

Where do you go for inspiration?

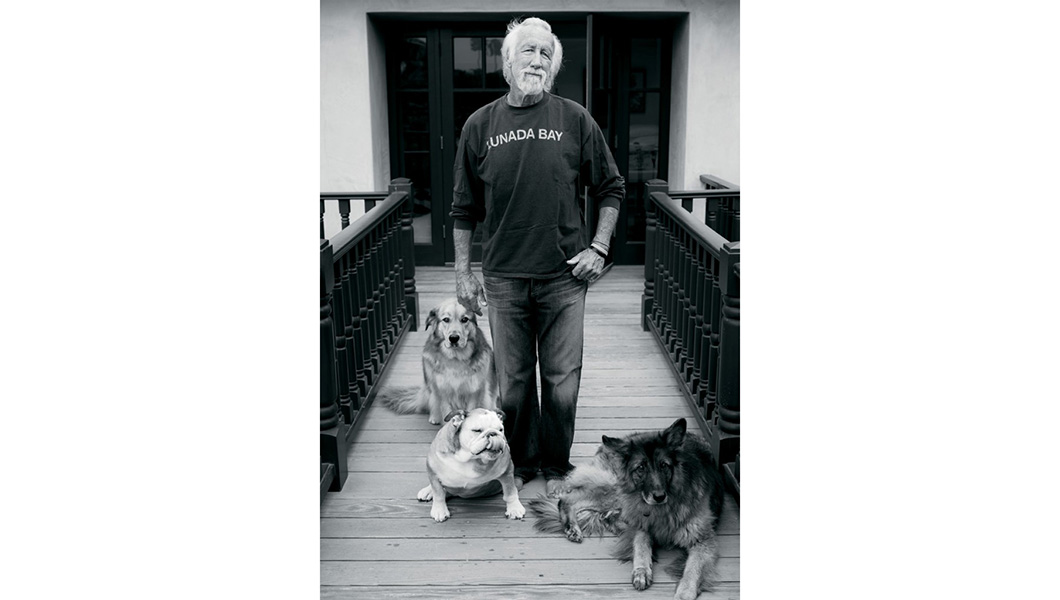

I built a house right on the ocean 20 some years ago here in Palos Verdes, so when you get up in the morning with a cup of coffee and nobody is up yet and you watch the sunrise and look over the ocean—it’s a pretty good place to have a clear head and kind of focus back in on the problem you are trying to solve, what idea you’re searching for. A lot of creative people in particular want to work at night. I’m actually the reverse.

—