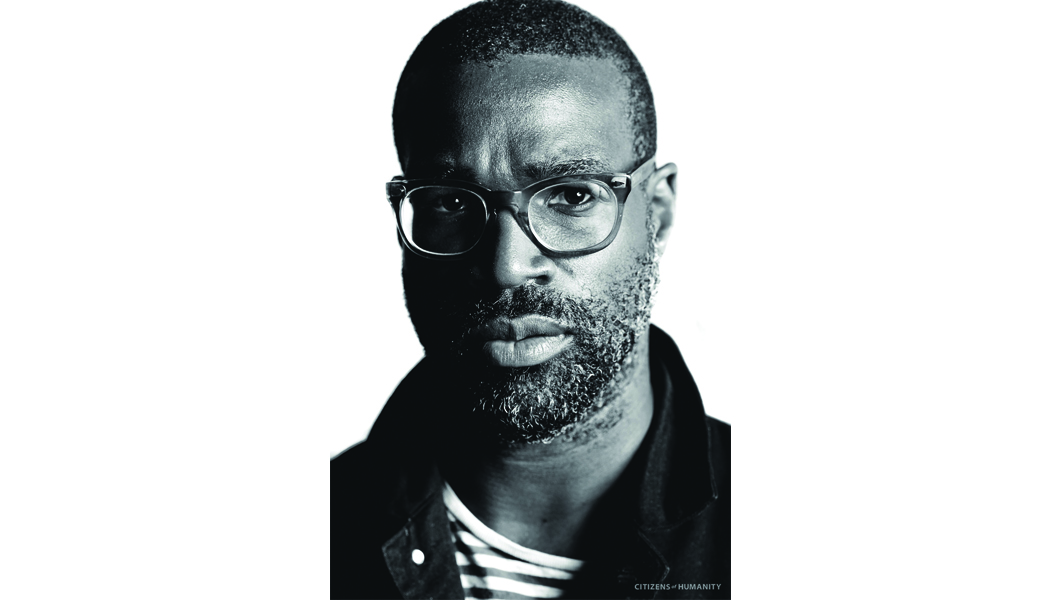

HUMANITY: What’s the source of your name? Where is it from?

TA: It’s from West Africa. My parents are from Nigeria.

HUMANITY: Your name is so rhythmic—it sounds like music.

TA: That’s good. It’s good that it doesn’t sound unlike music. That’s cool.

HUMANITY: So, listening to your demos, it’s amazing how it’s like night and day from the completed songs. When you come up with your ideas, what’s your process of turning them into songs? And then bringing that to a band, what do they add?

TA: Well, my process isn’t really a process. I often walk around and then I’ll hear a melody in my head and it’ll just get stuck. Now I sing it into my phone notes or something. But before, I would basically be walking around with the song in my head until I got home and then just kind of hummed it into a four track or harmonized with myself in a four track. You know, you get a melody down, and then you just put words on top of it quite randomly, and then … just little by little you shape it, you shape it into something that sounds and feels right to you. It can be narrative storytelling, it can be poetry, or it can be total nonsense. But yeah, my four-track stuff, it was an extension of keeping sketchbooks, you know? Where it’s just kind of like, OK, put this idea down and maybe later you can flesh it out, or maybe this is the final, you know. A lot of the friends I had when I started making music in New York, before TV on the Radio, was like a real kind of low-fi recording community where people who had no business using recording equipment or anything, they barely had any idea. So that kind of made it seem to me like I could do it. But yeah, I have these little sketches or notes on an idea, and when we started TV on the Radio, Dave [Sitek] and I initially kind of became friends over the fact that we had all of these four-track tapes of things we’d made individually. We just sort of traded them and listened. There’s a version of “Young Liars” on one of the demos.

HUMANITY: What was the inspiration for that one?

TA: It’s very different than the final version, but the whole song is pretty much there. Most of the songs that I put on that compilation were things that I felt could exist as vocals alone, like if I wanted to just go into a studio and record them a cappella, that I could do that. But then I met Dave, and it was sort of just like, “Oh, here’s this incredibly talented musician. We can work on stuff together, we can work on each other’s stuff.” It’s really weird—inspiration is a strange thing.

HUMANITY: Those songs are from 2003, right?

TA: Yeah, they came out in 2003, but the sketches—I found a tape that said “Four-Track Dumps 1999.” “Young Liars” was on there.

HUMANITY: Is there something that’s happening in your life that turns into a song for you or where does it come from?

TA: I feel like a lot of that stuff definitely, without sounding too weird and going into too much … I don’t even know if it shows up in the song, but it’s the closest thing I’ve had to a supernatural experience, and it was focused on a relationship and there was definitely someone or something besides the two of us. I refuse to believe that it’s just us.

HUMANITY: Is that why it’s called “Satellite”?

TA: Oh, no. “Satellite” is different. I think the version I put on there was something where Dave and I played with an idea, and it wasn’t really formed yet so we just kind of went and worked out the nuts and bolts of it, which also will happen sometimes when you have a song and it sounds really big but the internal workings of it don’t really do anything for me, or it doesn’t feel right. It’s like you fucked up a painting or something. I’m just going to sketch it out again and see what it looks like and then I’m going to go back and build up on it again. But sometimes with the things that feel slightly overwhelming, a song is a good way to put it in one place, so it’s not swirling around your head.

HUMANITY: What about some of the other songs you put on the compilation? “DLZ,” “Tonight,” “Reasons.” Is there a story on “DLZ”?

TA: I have no idea where that came from—that’s when it was in a Brooklyn loft with no heat, no nothing, and I feel like I found it. I was scrubbing through it and it’s going on like for 45 minutes, just those three notes. I got out of this crazy zone and then that broke and the second thing that I put on there was like the next layer of it, where I rerecorded something, put another layer on it. I didn’t have Pro Tools or any of that—I was literally recording on the tape, like a drum part and a keyboard part, and then getting another tape player and playing that out, and then getting a mini- disc recorder and playing it, so everything was happening, like a little orchestra with boxes in front of me. But I don’t know, this particular one. It’s hard to process, but the idea that everything we’re doing is destroying the planet. The intense arrogance of someone who thinks that you can win at life by making the most money or by hoarding natural resources for yourself. And again, you can think about these things and have a nervous breakdown, or you can kind of put them into a song and figure it out.

HUMANITY: It reminded me of Massive Attack.

TA: Very cool. I love that. Those guys are good friends—they’re really awesome.

HUMANITY: And then I was listening to “Tonight,” which is so completely different. Compared to how it turned into a song, I feel like your demos are darker, and when you bring it to TV on the Radio, it lightens up. How does your solo stuff differ versus TV on the Radio?

TA: I write all the time—well, a little bit. Since I moved, like a little bit less than I have for a while, but I’ll write, and something can sound like it could be a TV on the Radio song. Especially after being with the band for so long, I’ll just hear something and think, Oh, OK, I can bring this to a stopping point, and it’s a very concise song that I know the band could do justice to. If we don’t, then I’ll put it with the 200 other things that I’m never going to get to. I feel like with my solo stuff, and I feel weird even calling it “solo stuff,” because I just haven’t had time to put it out. I’ve performed by myself, just with some of those things, like a lot of improvisational vocal stuff. I have a couple of sets of songs that I’d like to do with just mostly voice and very minimal instrumentation, which I’d like to actually get to doing this year, because I’ll have some time. But now I’ll write a schedule. If I know that we’re planning on making a record, I’ll write in that direction. I feel like with my own stuff, it’s not as concise. I guess for better or worse, it’s not anything I can see being pop music.

HUMANITY: Do you think your solo stuff is going to be more in the realm of the demos on this record?

TA: Some of it, yeah. That’ll definitely be one of the textures. I was thinking of doing a 15-song set, five songs apiece. And I always think of things in terms of a complete art piece. One will be songs that are basically voice, guitar and drum—very, very raw. And five songs that are vocals with minimal electronic and then five will be completely a cappella.

HUMANITY: Do you think you’ll be releasing your solo record anytime soon?

TA: Yeah, I think later this year. We’re going to be touring until October. But realistically probably very early next year. If I can get something out this year, that’d be great.

HUMANITY: What’s your musical background? Did you play an instrument?

TA: No, I had very minimal piano training. When I was young, I was the least musical member of my family.

HUMANITY: That’s hard to believe.

TA: I know, but it’s true. My dad played the piano, my mom sings, my brother was an excellent piano player, my sister sings opera. I was terrible at piano—I couldn’t stick with it. So I started taking drum lessons when I was 12. I took two lessons and my drum teacher quit, because he got a job with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. But I was convinced it was because I was terrible, which shows you what a completely spineless, whiny child I was. But I sang in the choir in high school, things like that, but I never thought music would be how I spend most of my time.

HUMANITY: Did you listen to all sorts of music? Who influenced you musically?

TA: That’s a ton, a ton, a ton of people. There was always a lot of jazz in our house and classical music playing. My dad really liked Thelonious Monk a lot. We’d play Chopin and things like that. But I think that the first time I really started thinking about writing songs was when I listened to Nat King Cole and old rock ’n’ roll, Chuck Berry. My dad would find dollar tapes and just be like, “This is what you should listen to, don’t listen to any of that crap you’re listening to.” Trying to think of what else. As a teenager, Bad Brains, Minor Threat and Nirvana. I was a huge Nirvana fan. There was a period of time that I felt like, “I hope no one else ever finds out about this band,” you know. It was like 1990, ’92. And then people find out, and you’re like, “OK, cool, people found out, but they’re making good records,” and then it’s the cliché where the football captain or whatever is wearing a flannel, and he’s still a dick, but he’s dressed like someone who’s not a dick, and then the whole world … going on for 15 years, I still am sort of in denial that that band or his songwriting had such a huge effect on me, but it totally did. Nirvana and the Pixies and …

HUMANITY: What ignites you to keep on making music?

TA: I have the most boring answer, which is, “I’m lucky enough that it’s my job right now.” I should probably pay that luck back by doing it. It’s strange, because I’ll go through some periods of time where I really don’t feel like making music, and I used to feel really worried about that, but now I think it’s really healthy. I don’t believe in forcing yourself to do something. Whatever allows you to create; I just like making stuff.

HUMANITY: You guys have a huge fan base, and you have an effect on people as musicians. Are there messages or things that you intentionally try to share through your music?

TA: I’ve always just liked the idea of hearing something really personal, that seems to only mean something to you and then you can hand it off and you discover that someone else can use it in a way that you didn’t intend for them to use it. But I think of how much music and art literally changed the course of my life, you know. When I look at it now I’m really grateful. I just like the sort of message-in-a-bottle idea of it—not the Sting song, but the idea of putting something out to the world. You don’t really know who it’s for; it’s kind of for you, but it might be more valuable to someone else, like once you get through whatever you’re trying to do. But I don’t think there are any direct messages, except maybe we’re all on the ship together.

—