It’s a midweek evening inside the Pico Youth & Family Center in Santa Monica. Approximately 40 young people, a combination at-risk youth and teenagers aspiring to careers in the arts, are leaning forward in their seats toward a small stage set with a single microphone. A girl with artfully frizzy hair plays a soul-folk song, her own composition, and her young colleagues applaud and offer commentary and constructive criticism. Over the course of the next couple hours, these youths will take turns performing songs, poems and raps based around a single topic that had been assigned the previous week. Seated left of stage is Leila Steinberg, veteran community activist and the enthusiastic matriarch of this artistic assembly. The thoughtful, beatific Steinberg was Tupac Shakur’s first manager, a fact that secures her credibility in the eyes of the young people around her, many of whom were not born at the time of the hip-hop superstar’s 1996 passing but who still study and revere him as an inspirational icon.

“What is our point of unity?” Steinberg asks the assembly. A boy in a backwards baseball cap calls out: “We all want to express what’s in our hearts.” “That’s right,” Steinberg says, “and we do that by focusing on what we want to say with our voices.” The aim of this weekly workshop is to equip all the attendees with a healthy level of emotional literacy, and develop the most gifted among them as potential world leaders. As Steinberg tells them: “I want to mother you into being everything you can be.”

A mother of four, Steinberg does not use the verb “mother” lightly. The young people in her orbit are participants in a program called AIM (www.aim4theheart.org) that Steinberg founded 17 years ago, its roots dating back to a writers’ workshop she hosted in her Santa Rosa living room in the late 1980s that included a precocious teenage truth-seeker named Tupac Shakur.

A few days later, Steinberg is seated at a Highland Park café for this interview. Though she expresses trepidation that this article will focus on her personal story and not her work, her biographical details illuminate her mission. Her Polish-American father was a criminal defense lawyer working on issues of social inequality, her Mexican mother (who’d come to the United States at age 9) an organizer alongside Cesar Chavez and an activist with Amnesty International. Born in Los Angeles, Leila became an accomplished dancer and a member of the pioneering highlife group O.J. Ekemode and the Nigerian All-Stars, with whom she began to speak out as part of the anti-apartheid movement spearheaded by Amnesty.

“I understood how Amnesty leader Jack Healey built an entire movement with arts,” Steinberg says. “Tracy Chapman and Sting grew his cause, but they also were the work. I had an agenda which at the time I wasn’t able to frame. All my father’s clients were black and brown. My questions started in elementary school. The first placed I lived was 64th and Vermont, then we migrated to the La Cienega area, then migrated to Santa Monica, then Malibu. I was well aware of the privilege I had because my family understood the power of education and we had access. We had upward mobility and access and I knew there was an injustice in that. That drove me.”

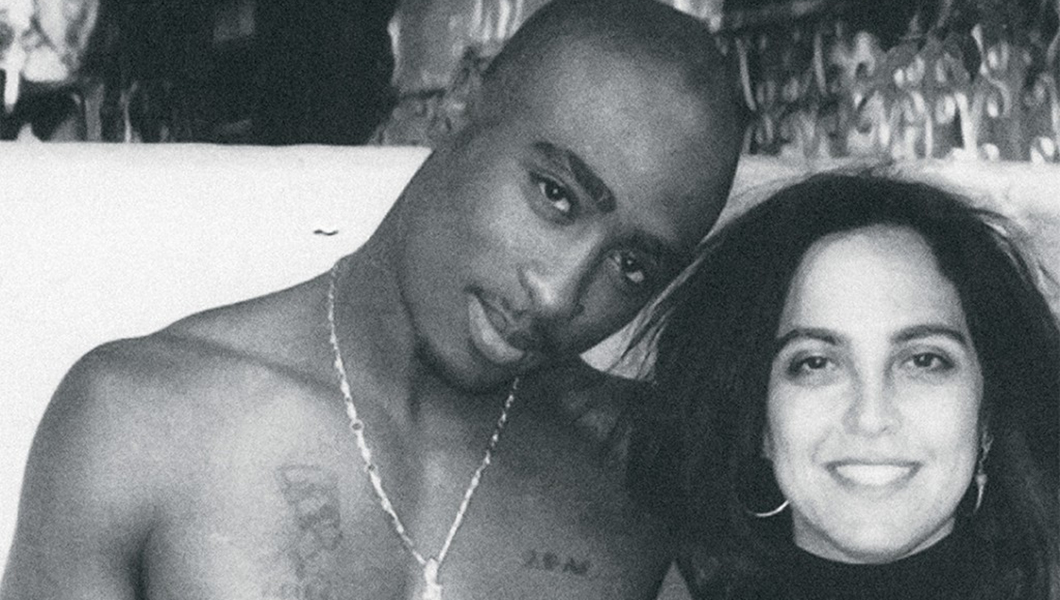

When she became a young mother, Steinberg and her family relocated to the San Francisco Bay Area. Her husband was a DJ and nightclub promoter, and one night a 17-year-old Tupac came to dance at her husband’s club. That was the first moment Leila Steinberg saw Pac, and by cosmic design the pair ran into each other again the following day. “I was sitting on the grass in a big field in Marin City before starting to teach class,” remembers Steinberg. “I was reading Winnie Mandela’s Part of My Soul Went with Him, and Pac happened to walk by. He said, ‘What are you doing with that book? What do you know about Winnie Mandela?’ I said a lot, actually, that I was involved in the anti-apartheid movement. We began talking about issues that interested us, and he became a part of my family from that moment.

“My life became consumed with making Pac matter to everybody. I believed he was the one, like Bob Marley and many before him. It wasn’t just about arts. It was about social, political and educational aspects. It was about everything but entertainment for me. That was a by-product. Of course Pac could be entertaining. His art was, in its inception, for the sake of greater good. How can you raise a generation who are not wanted? Tupac was obsessed with the pain and imbalance in his community—all of the issues that he was born and cultivated to address.”

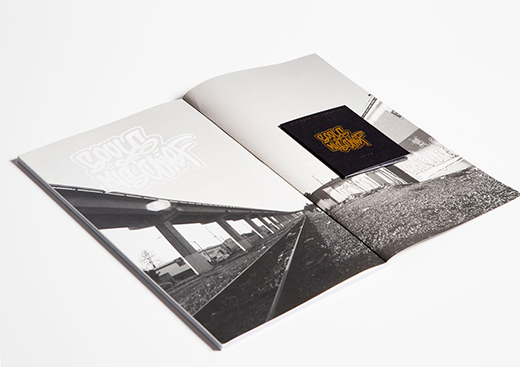

At Tupac’s behest Steinberg became his first manager, and the two worked closely during Pac’s late teenage years to refine his artistic mission. Steinberg is jointly responsible, along with Tupac’s mother, Afeni Shakur, for putting together Tupac’s best-selling, posthumous book of poetry, The Rose That Grew from Concrete (MTV Books, 1999). Comprised of poetry written during Tupac’s teenage years, the book has influenced subsequent generations worldwide.

“I wanted to get the book published while he was still alive,” says Steinberg. “I’d been reading those poems in classroom workshops for years. I’d open an assembly to 2,000 kids by reading the Tupac poem “Lady Liberty Needs Glasses” and have kids talk about what he meant by that. There are now classes at every Ivy League school on Tupac! Two hundred years from now when people want to understand what was happening in race, politics and music, they will study Tupac.”

With a John Singleton–directed Tupac biopic in production, Steinberg has only recently begun speaking to the press again about Tupac after years of grief-darkened silence. “In a sense I’m doing more work with Tupac today than when he was still here,” she says. “I’m using his poems every day, and I thank him every day. Now, after 25 years of process, I actually feel I can step out into the world and bring something viable to the way we impact our youth. I really want to make a difference, still. I haven’t changed.”

With AIM, Steinberg has created a no-cost curriculum called Heart Education that can be used in any setting where “heart work” is needed. “It works in juvenile halls, in prisons, in thirdrate classrooms,” Steinberg says. Tupac’s poems are an embedded part of that curriculum. Back at the Pico Youth & Family Center, the evening gathering is winding down. Some of the young people speak excitedly about a pending trip to Hawaii, where Steinberg will lead workshops for children on the island, and offer training in her emotional education curriculum. Steinberg announces the topic for the week’s writing assignment: revelation. As hugs and promises of “See you next week!” fill the room, Steinberg offers everyone some parting words of inspiration: “Remember, the reason Tupac is the most studied artist of his generation is because of his heart work.”

—