Imagine having the potential to be the best in the world at what you do, yet also knowing there’s a pretty good chance many people will never believe you got there honestly, no matter what proof you provide. And then just saying, “Who gives a shit. I’m doing it anyway.” That kind of mindset requires a very rare combination of qualities, including (but not exclusively): world-class talent, bulletproof confidence and balls of steel.

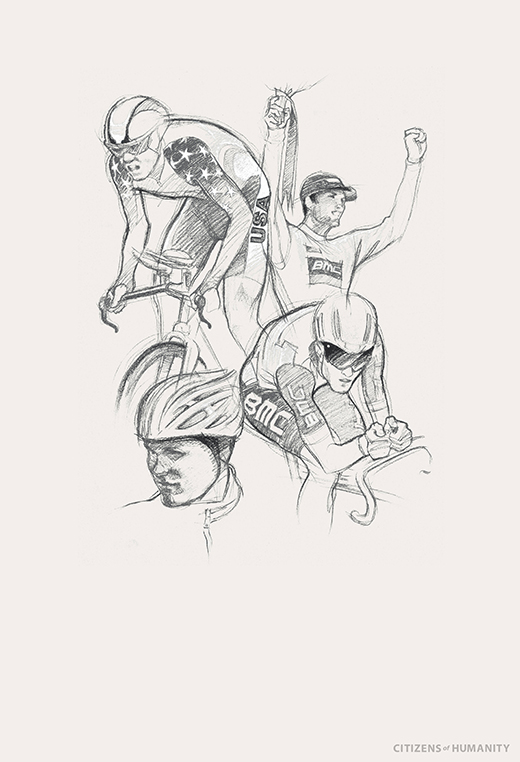

Welcome to the world of Tejay van Garderen, a man competing in cycling, a tarnished sport that is still on its path to resurrection following a catastrophic doping scandal that spanned and discredited the results of 20 years of accomplishments, and the best and brightest hope for America since Lance Armstrong, perhaps the most reviled athlete in the history of popular culture. If this were 2000, van Garderen, a handsome, supremely talented 26-year-old who has done everything the right way, who finished fifth in the Tour de France last year and who is now poised to take home the title this summer as the unquestioned leader of the BMC Racing Team, would be a media darling. But as it stands now, van Garderen is flying well below the radar of the zeitgeist, and that is probably a good thing. Too much scrutiny at this point would only invite cynicism by the public at large, thanks to Armstrong’s sociopathic behavior during his now discredited seven Tour wins and the revelations that every other top rider during his era was doping as well. It will all shake out this summer. No pressure.

Van Garderen was born in Tacoma, Washington, but spent his formative years in Bozeman, Montana, a picturesque Western city with ravishing mountain vistas and a noted hub for outdoor sports junkies. It was there that his stepfather, a Dutchman named Marcel van Garderen (Tejay took his last name after being legally adopted), turned the 9-year-old on to cycling. The kid was a natural, especially when it came to climbing, the sport’s most grueling, oxygen-depleting, lactic-acid-inducing, soul-crushing subdiscipline, and by the time he was 18 he had already won 10 junior national titles. He turned pro that same year, then began his ascent to potential greatness.

Regardless of his future accomplishments, it is a near certainty van Garderen will be judged within the Armstrong prism, an unwarranted fate by any standard. A much more apt—and fair—comparison would be Greg LeMond, the last clean American cycling superstar and unquestioned winner of the Tour three times (1986, 1989, 1990). Like LeMond, van Garderen married very young (van Garderen got hitched to his longtime girlfriend, Jessica, at 23; LeMond was 20 when he tied the knot), moved to Europe because it was the only way to perfect his craft, did so without the requisite linguistic or cultural skills, began his career as a domestique (a supporting player, in cycling lingo) and then emerged from the peloton with a giant target on his back thanks to his nationality. But LeMond didn’t do it in the shadow of Lance. And van Garderen is, for now, just a prospect, not a winner. Not yet.

If van Garderen does in fact bring it home on the Champs-Élysées in July, wearing the yellow jersey with the customary glass of champagne in his hand as he crosses the finish line, he insists he’s prepared for the inevitable scrutiny that will come with a Tour win, especially one from an American. “I’m proud to tell people I’m a cyclist, regardless of whatever they think, or whatever insinuations come along with that,” says van Garderen. “Cycling obviously has an unfortunate history, but there’s been a lot to clean things up, and hopefully the public starts to trust that, trust the testing and trust the athletes. It’s a clean sport now, so I can’t really speak to the past. I wasn’t there. I came in after all of that stuff.”

—