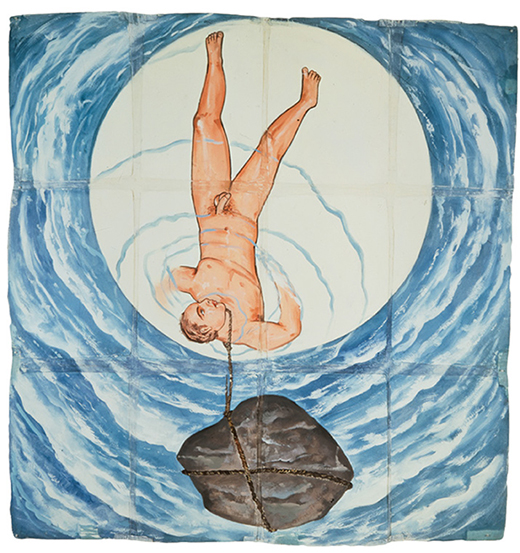

Francesco Clemente is stark and intimidating, not unlike his artwork. He speaks carefully and briefly, without a sign of chattiness or informality. Clemente’s wide-ranging works of the 1980s, often centering on stark, confrontational representations of the human body, defied much of the abstraction in favor for the previous decade. His painted imagery could simultaneously evoke sexuality and religious allegory, with portrait subjects staring the viewer squarely in the face. Born in Naples in 1952, Clemente moved to Rome in 1970 to study architecture at the University of Rome. He soon began to work as a visual artist, and at age 24, he met his future wife, Alba Primiceri. The couple soon had the first of their four children and moved to India. By the beginning of the 1980s, the couple and their children were in New York City, but Clemente returned frequently to India, completing his 24-work 1981 series “Francesco Clemente Pinxit” in collaboration with Indian artists trained in miniature painting.

In New York he became an art star, collaborating with the young Jean-Michel Basquiat and the older Andy Warhol. Clemente also created works in collaboration with or to accompany the works of poets Gregory Corso, Allen Ginsberg and Robert Creeley. Along with Alba, who was a frequent muse to and portrait subject of many of their renowned artist friends from Basquiat to Alex Katz, he would spend evenings at the great New York nightclubs of the 1980s: Danceteria, the Palladium and the Paradise Garage. Clemente never ceased traveling, however. He maintained homes and studios not only in New York but also in Rome; Taos, New Mexico; and Chennai, India. Today he and Alba live in a Greenwich Village home that belonged to Bob Dylan in the 1970s, and he maintains studios in Manhattan and Brooklyn. It is India, though, that has perhaps been the center of his creative energy for the longest. Having long collaborated with Indian craftspeople in connection with his art, Clemente continues to work alongside them in his most recent series of tents, which are sized to hold dozens of people standing within them and are densely painted and printed both inside and out. Evoking nomadic cultures around the world, the tents are made in India, each taking a year for Clemente and a team of Rajasthani woodblock-printing artists to create. They’re a spot-on metaphor for Clemente himself, the nomadic artist, ever wary of easy categorization, to set up an identity he can take down and take away anytime he chooses.

New York City’s Rubin Museum will present a show of 20 of Clemente’s India-inspired works in September of this year, and Mary Boone Gallery will present two new tents in November.

What was your childhood like in Italy?

I grew up in Naples, a city somehow broken but full of wit and cultural arrogance. My parents had modest means but managed every summer to travel by car to a different European country. By the time I was 12 they had taken me to see every monument or museum in Europe they could think of.

You briefly studied architecture in 1970. How did you end up becoming a painter?

The faculty of architecture in Rome was then the hotbed of anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist activism in Italy. There was much violence and turmoil and, to my eyes, opportunism. In an early catalog of my work I remember writing: “I am looking for a territory without enemies.”

What compelled you to want to share your thoughts and ideas through art?

I had an exaggerated awareness, from an early age, of the dynamics of power. All knowledge appeared to me a tool for domination and exploitation and hence a lie. I didn’t want to be part of the lie. To become an artist was the way out.

How did you come to collaborate with Basquiat and Warhol?

Bruno Bischofberger, who at the time was one of the few who had respect for both Warhol and Basquiat, suggested we make some works together. This was easily done. Our studios were close to each other. We were close, too. Warhol’s Interview magazine had covered my work only a month after my arrival to New York. Basquiat and I had common literary likes, particularly the Beat poets.

What was it about their work that you made a connection to?

I relate more easily to “big” art. By big I mean art that crosses its cultural context and aspires to express a worldview. Both Warhol and Basquiat, in different ways, shared this aspiration.

You have also worked with many poets. How has that medium inspired yours?

Yes, to use the words of John Wieners, I pray every morning, saying: “Poetry visit this house often.” Ginsberg, Creeley, Wieners continue to inspire me, not just with their words but also with their character.

When did you first travel to India and what sparked that desire?

The same motive forced me to become an artist and to travel to India. I was discontent with the boundaries of Western culture, the culture of want, of “I” and “mine,” a culture that claims to have defeated poverty, whereas it has made poor even the rich.

How did Indian culture begin to influence your work from that point on?

In India I learned my favorite prayer. It goes like this: Oh Lord protect this body, protect this mind, protect this intellect, protect this ego [three times]. I am not this body, I am not this mind, I am not this intellect, I am not this ego [three times].

How does your work relate to the artistic practices and traditions of various regions in India?

I am attracted to cultural contamination, to inclusive views, to rituals, to handmade things, to anonymity, to anything that looks worn by time, to anything that has a feel of poverty and nobility at the same time. I encounter many of these qualities as I roam across India.

In contrast to the conceptual art practices of the 1970s, why did you choose instead to include representation, narrative and the figure in your work?

I did not choose. I made room for a work to happen. The work manifested itself this way. Sociological concerns just don’t seem so important if you begin to listen to the troubling noises of mind and body. “Ready-made,” “appropriation” are excellent tools if you want to show what art is. I am more interested to show why art is; hence I paint and draw.

You have explored a variety of more traditional, artisanal materials and modes of working. Can you please share how that evolved for you and what those processes and materials are in your artwork?

The work mimics the fragmented state of the world. It mimics a world in flux, where the only constant is “the continuity of discontinuity.” Not only do my mediums change all the time but also the supporting surfaces of my paintings are never the same for long. By doing this I chase the ever-changing nature of our perception and aim at stripping it naked of conventional truths.

In 2013, you had an exhibition of tents, something different from your usual exhibitions of paintings. How did this come about?

I had spent time in China, and from China the world appears bigger than ever. I felt challenged to make larger, more public paintings, but I didn’t want to lose softness, vulnerability and sensuality of touch. These are the tents—they are enormous paintings you can touch, smell, sleep in.

The tents are all hand-painted, inside and out. How does that influence the experience the viewer has, even though they are inside a gallery setting?

The beautiful thing about handmade things is that they always make room for something unexpected to happen. In this case I had not anticipated that the painted walls of the tents were going to be viewed in a dim light, the same light of ancient churches or primordial caves.

How do you unite your Western aesthetics with your interests in Eastern mysticism and spiritualism?

All these divisions, East and West, North and South, are an invention of imperialist and consumerist politics. If you want to invade a place with your armies or with your products you have to make everyone believe that the place is different than your own and that it is an empty place. To the eye of the poets and the artists I admire there is no East or West, there is only a suffering mind or an awakened mind.

How do you use symbolism in your work? Why is it part of your artistic language to use symbols?

The loss of the sense of the sacred and the loss of a symbolic language is at the root of the ecological catastrophe we witness today. Rational thinking is not enough to defend the mind from itself. War, genocide and the destruction of the earth are conceived of “rationally.” They are the sum of “rational” decisions.

—