PAOLA KUDACKI: Hello Carmen. Thank you so much for having us in your home and at your studio. It is super nice to get to see your work and your process—it’s like being inside of your brain, among your ideas and inspirations.

I wanted to feature you because you’re an incredible artist and also because this issue is a bit inspired by motherhood and people who are inspiring to me. This year I became a mother, and as you know, life changes so much with that. And the idea started a bit about being a letter to my daughter, highlighting women who are passionate and courageous.

CARMEN WINANT: It’s funny that you’ve thought of the issue as being a letter to your daughter. I was thinking how I regard so much of my work as being like a letter to my mother. So much of it is directly or indirectly addressed to her or about her. It’s so interesting to think about it moving in the other direction.

I think so much about my mother with my work, not only as a mother but also as a feminist, and as a feminist who in a lot of ways had to make compromises with my work in order to have children.

PAOLA: For me, definitely having a daughter has made me think so much and understand so much about my relationship with my mother, and how that affects me, and what I want to project to my kid and on my work.

CARMEN: Yes, it takes a lot of unpacking. But I have this strange conundrum where I feel like being a mother and having kids and giving birth has so informed my work; on the other hand, my children pull me away from the studio and make it harder to be an artist. There’s this push-pull. I don’t know if you feel this with your daughter, where they change your work, and they make your work better and richer and deeper, but they also make it harder to do your work. It’s this constant negotiation.

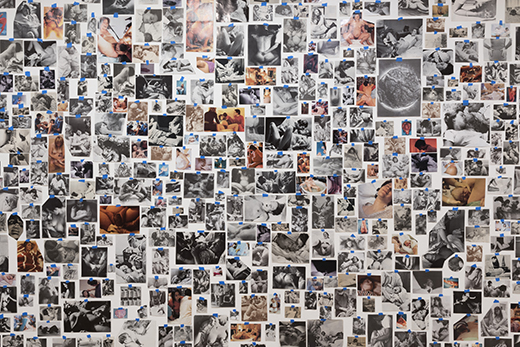

PAOLA: Most of your work is collage. How did you up with the idea for “My Birth,” the collage you did for MoMA in New York in 2018.

CARMEN: I think the trigger of it, initially, was after I gave birth the first time. It’s like you were saying, this animalistic effect. I couldn’t believe the process of giving birth. It was so many feelings all at once. I felt as though nothing could have prepared me for it. I was just shocked that people gave birth and then went about their daily lives as if nothing had changed, because it was such a fundamental change for me to undergo that experience. I had been working with images for a long time. I’ve always been compelled by the idea that images can try to describe an experience, but they can never quite do it.

Images of birth for instance—they can’t actually transmute the feeling of giving birth. They’re remarkable, yet they can’t somehow express what happened. I had this idea that I would try. That I would try to see if I could just collect images—image after image after image. Then if I had enough of them, maybe I could describe the feeling of giving birth. Of course, knowing you can’t really ever do that with pictures.

PAOLA: Also, when is enough?

CARMEN: Right. Also, I went through the experience, and I thought, “Why aren’t there more representations of this in culture?” It’s like you were saying, TV and movies and the popular culture is where we get the information. It was nothing like that. Like you slap your husband, you punch your doctor and your baby shoots out. It’s now so comical to me to think how that was what I thought giving birth was like. It was also an intent to create a vocabulary or to make birth visible. Not only in a piece of art, but in a piece of art in the MoMA. That was going to be really visible to many different people from many different cultures.

It was an amazing thing to walk through and eavesdrop on people looking at it and talking with their mothers and with their children, or putting their heads down and walking through and not wanting to make any contact with the piece. It was actually people’s participation with the work that made it so much more complicated than I could have imagined.

PAOLA: The thing is, giving birth is something that humans and animals have been doing since the beginning of time. But we never get to see the reality of how it really is. And every experience is very personal and very different and very special.

When I was at the hospital and I had my daughter, I asked the doctor about how many women gave birth that night. When he said 33, I couldn’t believe it. I was in such a trance, feeling that the world had stopped.

CARMEN: Because when you’re inside of it, it’s so big. It’s so powerful and overwhelming. I remember at one point when I was giving birth, I heard a woman’s scream in another room who was also giving birth. I had that same experience where I was like, “Someone else is also going through this.”

Every step of the way. Even before giving birth, I was just so amazed. That’s not even a big enough word for it by the experience, when you start to feel a body moving inside your body. I had already been thinking about it, but then when it happens to you, no matter how intellectually prepared I was, I felt totally floored by the experience.

PAOLA: What is motherhood for you?

CARMEN: Oh my God, it’s such a big question. I read a quote recently—God, I can’t remember it. It was by some famous feminist writer. She said motherhood for her was ambivalence. I thought in some way that describes it, because it’s so many things at once and it’s also a pull between things. I feel tenderness, enormous tenderness, and I feel patience, and I feel deep love toward my kids. I also feel frustration, exhaustion, sometimes even resentment that I can’t do the things that I want to do. I can’t take care of my needs. Somehow, for me, at least, it’s like the simultaneous play between all of those feelings at once. How about you?

PAOLA: I’m new at this. But there’s really no words to describe it. It’s something that is new all the time.

CARMEN: I would say so. I remember actually when my son was born. I remember he came out, and it’s of course just an intensely emotional experience. I felt this new feeling. A lot of it was fear. I really felt I just wasn’t sure how to take care of this person.

PAOLA: For me it really puts aside the word “perfection” or “control.” Being a mother is a constant unknown and surprises, and continually adapting and changing. It’s living in the moment because you can’t control the future.

Carmen, you are a mother, an artist, a professor; you have a lot of people who are looking up to you. How do you inspire young generations to create and how do you give them tools to be better and encourage them to follow their dreams?

CARMEN: I love teaching. It’s a good gig and allows time to be an artist; it makes it possible and supports that endeavor. I’ve noticed actually lately that students are making less political work. I would think that now, of all times, it would feel urgent to make that kind of work. I’m generalizing here because I definitely have students who are really interested in that, but I try to encourage them to make work that has some stake in the world.

I think the big challenge of being a teacher is to help them to understand that they live in a community and in a world. That their work can and should relate to a life outside of themselves, ideas outside of their own.

PAOLA: Do you think that social media has affected the way artists, or young kids as future artists, develop their work?

CARMEN: Separate from being a professor, as a parent [it’s a challenge] to figure out how to manage your kid moving through that social media landscape. I’m just thankful that my kids are so young, so I don’t have to deal with it yet. In terms of my students, yes, I think they spend so much time looking at themselves in this little insular world that is their device. I don’t know how I would have been. I imagine I would have been a totally different artist.

PAOLA: I think it must make them question who they are a lot, because it creates a lot of insecurities. Because you are continually being judged, getting likes or not, getting comments that are not necessarily encouraging.

CARMEN: I resisted it for as long as I could because I was afraid of this very thing that you’re describing happening. Like at such a vulnerable, impressionable time in their lives figuring where their worth is. They are literally born into Instagram.

PAOLA: Maybe their brains are trained to understand things differently.

CARMEN: I’m sure you’re right.

PAOLA: Also, they have a different rhythm in the way that they approach things. Their attention span, the way they look at things. They live a faster life. Everything is more accessible, so they look at things and then move on to the next thing quickly. We already live a faster life than our parents.

CARMEN: It’s been so nice to talk to you. I feel like you’re an old friend. It’s so easy, I mean it. You’re so relaxed and insightful and kind.

PAOLA: We’re moving in. [Laughs.] Thank you so much for having us in your home and in your studio! I feel the same way! Thank you!

—