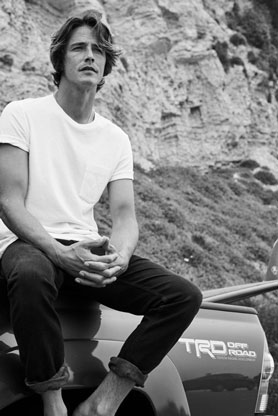

“I was bred into the surfing culture,” says former pro surfer Luke Stedman. “It was in my blood, in my DNA.” The son of revered board maker (and Ugg boots inventor) Shane Stedman of Shane Surfboards, Luke was raised in the water. “I knew more about surfing when I was five years old than I did about anything else,” says the Australian native, who vividly recalls the first time his dad pushed him into the waves (“I was on a little white raw foamie and I remember just getting the most incredible rash on my stomach”). But it wasn’t until his teenage years when the younger Stedman began to view surfing as a career path, and a way to travel the world. “I was okay, but a lot of my peers were better than me,” he confesses. “Going out and getting a job wasn’t really sort of my idea of fun, and surfing professionally was a lot more appealing. So, I took that avenue.”

Looking to gain a competitive edge, Luke not only enlisted the help of technical trainers, but also turned to spiritual and mental guides, too. “It wasn’t very common for the guys to have those sort of coaches,” says Luke. “I was never really expecting to do that well, and with all the wonderful people that were surrounding me and I was working with, I managed to get really good results.” In 2008 at age 32, he placed eleventh in the world.

Retiring from the surf circuit at age 35 (“I’d been doing it for such a long time, and I still loved competing, but I wanted to do something else”), Luke turned his attention to more creative endeavors, splitting his time between Los Angeles and his hometown of Sydney.

But he didn’t hang up his wetsuit forever; today, the father of one regularly hits the waves as a surf instructor for the Muse school in Malibu, teaching budding young surfers how to strategize and overcome mental hurdles in the water. “Surfing is such a personal sort of sport, and at times, when you’re having a rough day, there’s nothing will make you feel better than just going for a surf, getting in the ocean and just getting some salt between your ears,” says Luke. “You could have the worst surf in the world, and come in, and still feel better than you did when you, before you went out. That’s what surfing does for me.

Why was it important for you to work with both mental and spiritual coaches as a professional surfer?

When I was competing, it wasn’t very common for the guys to have those sort of coaches. But I just knew I needed an edge, just because there were so many guys who were naturally more talented than I was. I felt if I worked with those people, that would give me the edge, I’d be able to use those angles to my advantage. And it really worked, because it wasn’t till later on, I realized that competing was 70, 80 percent mental. It’s such a large portion of why you compete well. So, it sort of changed my mindset a lot. Then I started focusing really, really intensely on a lot of mental of strategies. That’s essentially what gave me the edge, and what allowed me to compete at a high level.

Is that a philosophy you’ve brought into other parts of your life as well?

Absolutely. Having a strategic game plan, and knowing how to use particular tools and particular situations, and strategize—I just don’t feel people do that very often. It was great to have that learning curve of doing something, and I’ve been able to take those skills away with me and use them in my day-to-day life

Best piece of advice you’ve ever received?

I’ve heard some wonderful bits of advice, like coming to each moment and each encounter expecting magic, or going in with just an open mind, and thinking the infinite possibility of what may be. I feel like that’s a really wonderful way to sort of lean into everyday work. If you can go in with that mindset, then I feel that really changes things, and that’s been working for me lately. My dad is consistently giving me advice, and it’s all been really good. Half the time, I would often think that, I’d be like, “Oh, it’s just Dad, that’s silly advice,” but then as the years go down the track, he’s actually right, which is frustrating. He would often tell me things along the line of “Never put off till tomorrow what you can do today.”

In what other ways has your father inspired you?

My dad has a really special energy. He deals so well with so many people, and he’s always smiling. He has a great way of dealing with all sorts of life challenges, and he’s very resourceful. He’s a grateful person, and someone who is always there for you and very supportive. He’s a gentleman. I couldn’t say a bad word about my father. He’s been a huge part of my upbringing, and I value everything that he’s done. I respect him, and I love him dearly.

How has he shaped your own take on fatherhood?

He’s continually there for me for support now, like when I have questions about my son he can relate to me, because he went through the same thing [as a father]. I can ask him questions, and things to be ready for, and how to deal with them potentially when they arrive. Having a kid, you never know what’s going to happen. I feel like he did a great job with me and my family, so I’m happy to ask him and my mother [for advice]. She’s a very special person as well. She has a fabulous take on life, and she’s very caring and loving. I just feel super-blessed with my family. I’m a lucky, lucky man.

What do you consider your greatest personal achievement?

Definitely being a father. My kid is a reminder every day of how special life is. I guess dads say that. It’s a cliché, but it’s true.

What’s the biggest challenge you’ve ever faced?

Stopping surfing competitively, and then diversifying onto the next life challenge and going into the workplace. You’re doing what you love, you’re getting paid really well to ride waves for a living, and then having to learn how to read spreadsheets, and work incredibly long hours—and being a complete virgin on most of those things. I loved what I did, and that’s why I became reasonably good at it. So, I had to find something that I loved, and that was a challenge. And now, I found that. It took a bit of time, but it’s well worth it. I’m very grateful for what I do now.

When I started coming off the tour, that’s when I actually studied and got into meditation, and I was reading all these books on philosophy. Every person, whether it was, Deepak Chopra or Eckhart Tolle, they all say meditation was the most powerful thing they did. So, I jumped into meditating, and I’ve been doing that for seven years. That’s a really big part of my life now.

What’s the most important lesson you learned in the water?

Definitely not to take an ocean for granted. That’s probably the number one. You just never turn your back on the ocean. It’s such a powerful place, and it’s beautiful, but it can also turn on you so quickly. It’s one of those places where you never know what can happen out there.

Now that you’re no longer competing, do you get a different sense of enjoyment from surfing?

Yeah, it’s a different sort of love. There are a lot of times when you’re training and sometimes you don’t want to be in the water, and it’s cold and it’s windy. You’ve already surfed twice that day and you don’t want to hop on a plane the next day and go to a place that has really small waves. It can be really trying. You just miss home and you miss family, and it’s exhausting, but it’s still part of a job, and you’ve got to change your mindset and love what you do, and get focused, because otherwise you don’t compete well. And I found with me, if I wasn’t happy when I was surfing, then I wasn’t surfing as well as I could. So, that was a challenge. But now when I surf, I get excited just going out and surfing with Spike, my boy, and pushing him into the waves and seeing how excited he gets. That is probably the finest moment that I get now out of surfing, just watching him surf.

—

RETURN TO THE HOME PAGE

VISIT CITIZENSOFHUMANITY.COM