Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable

There is something mysterious about the sea. People don’t know what’s in there, and most don’t care to know. For some, however, the exploration is paramount to their existence—the adventurer who dares to take on the most unlivable environment on earth. Well, at least for us land dwellers.

To explore is to satisfy one’s curiosity. Some are far more intrepid than others, needing not only to find, but also recover, those curiosities that they find, in order to go some way toward explaining their own desire for discovery to the world.

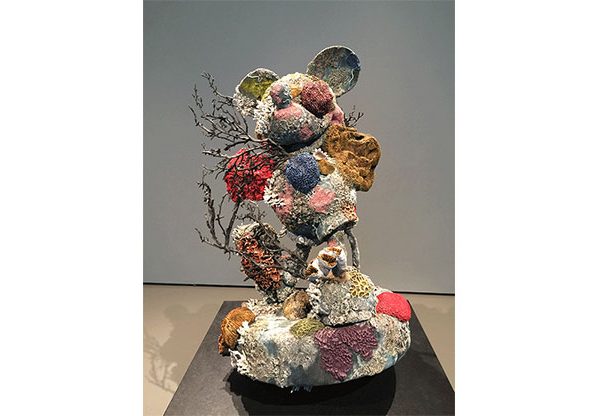

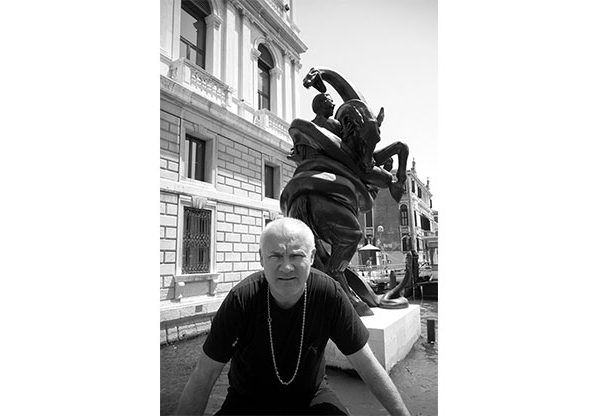

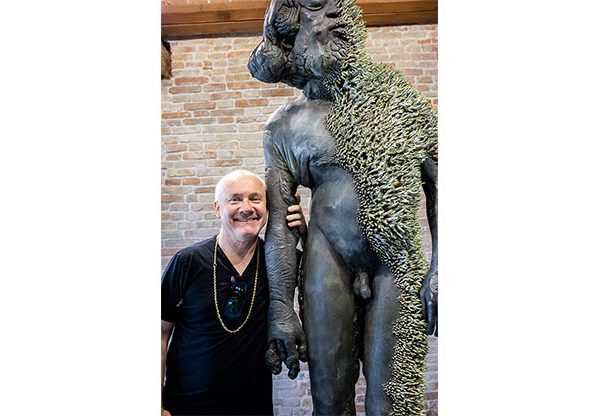

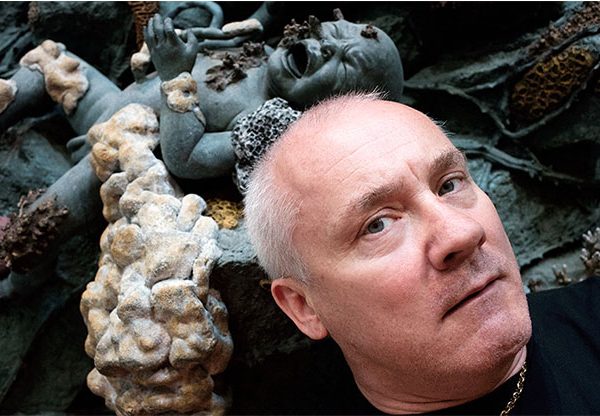

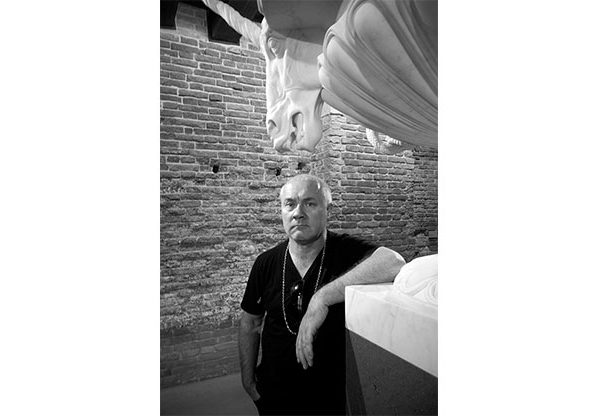

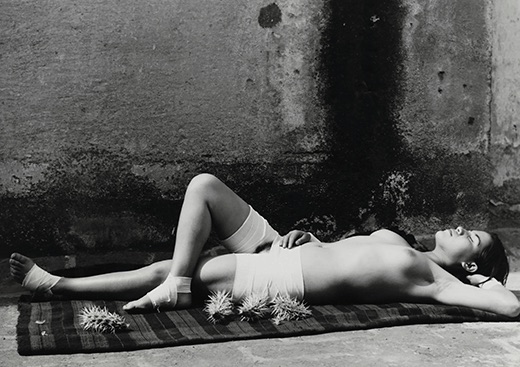

Perhaps this is the secret to the beauty and wonder of Damien Hirst’s Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable. One needs to do nothing more than invoke a sense of true wonder to create the most incredible immersive experience. For those visiting for their first time (or those less observant among us), the story is of these colossal sculptural creations being pulled from the ocean, the discovery of a huge collection of lost artworks.

The concept is simple yet strong, presented in such a way that anyone can understand it and appreciate it. But unlike so much modern art, the works that accompany the concept are even stronger.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

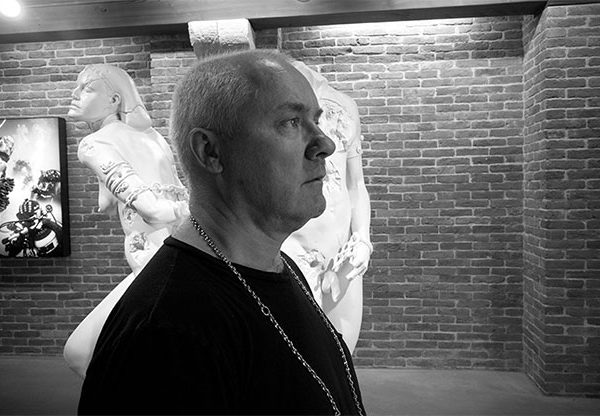

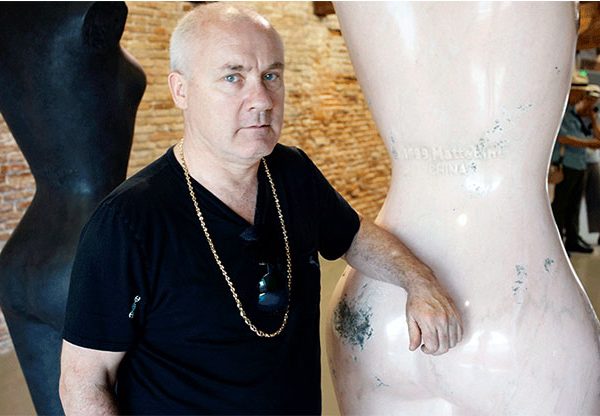

SASCHA BAILEY: So, in the show Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable, what is the basic concept and what do you want people to leave feeling?

DAMIEN HIRST: Confused. A lot of people think that, as an artist, you have to tell people what to think, but I don’t agree with that. You just set up triggers that make them think, and then you want them to make their own minds up. I want them to think about the present, but by thinking about the past.

SB: Where did you get the idea to make it look like you’d recovered it from the ocean? Where did that come from?

DH: I did the diamond skull and I was quite shocked that I had managed to make that, and I just sat looking at it thinking, “How the fuck have I got myself into this position?” I was just doing shit paintings in Leeds not long ago, thinking, “I’ll never be anyone, I’ll never be any good.” And then suddenly I’ve got this skull made out of diamonds that costs millions and millions of pounds, and I remember thinking about the idea of treasure because of that. Suddenly, I’ve made an object that could have been made by emperors and kings of the past, and I was just wondering how the fuck an artist had got himself into this position.

I did the Beautiful Inside My Head Forever auction at Sotheby’s in 2008, which was a lot to do with facts and science and logic, which I really believed in, and I wanted art that reflected that. And then overnight I turned to fiction—I don’t know why, I just switched, and I suddenly realized that the only thing you can believe in is the gaps between things. If we’re given a fragment it’s a lot easier to believe that it’s 2,000 years old than if you give someone something solid and whole. So I realized that you can inhabit fragments, and you can inhabit the gaps. Belief is about what’s not there—you believe in what’s missing. Like the Venus de Milo with the arms missing; you can really easily imagine it, how it was, and you believe the complete image you have in your mind. You love it more somehow.

SB: When you think to before your art was as valuable as it is, do you think that it’s changed a lot since then? Have you adapted it?

DH: I think it changes all the time. All the artists I love, you can see what’s great about them in their very early works, sometimes even when they were kids.

You somehow have to remain true to yourself. That’s difficult when no one’s interested in your work. It’s also difficult when everyone is interested in your work. You’ve just got to keep an eye on who you are, and make sure that you’re not producing bollocks.

I suppose it’s a confidence thing. When you’re young you don’t really have a lot of confidence, but you have to be confident about who you are—that’s what makes you become an artist. I try and find parallels between what I was trying to do at the beginning and now, because maybe I wasn’t shit, maybe I just thought I was shit. But I think everyone can make great art. That’s the power of belief.

SB: What do you think is the next direction in art in general?

DH: I don’t know. I never know. I think it keeps changing. It’s a bit like when they asked John Lennon why he cut his hair in 1970, and he said, “Well what the fuck are you supposed to do after you’ve grown it!” There’s nothing you can do, you shave it! So it’s a bit like that; painting’s dead, painting’s back, painting’s dead, painting’s back. Art to me is always a reflection of the world we live in. As the world gets more complicated, the art gets more complicated. It’s like art’s trying to keep up with society.

There is always great new art. It’s like in music; a lot of my friends are musicians, and a lot of the older ones are always saying the new ones are crap. As an artist you’ve got to not do that. You’ve got to believe that the greatest art that mankind has ever made is around the next corner, rather than around the last corner.

SB: Is art the explanation or is explanation the art?

DH: I suppose it goes both ways. Conceptual art, to me, it’s always got to have feeling, it’s got to be emotional. I get bored of talking about art, really. I mean, if it looks good it is good. That’s the only rule. There are no other rules. If it looks or feels good, then it is good. You don’t need to know why it looks good. “Do you like it?” “Yeah, it’s fucking amazing.” “Why?” “I don’t know.”

That’s the perfect reaction to art. I don’t think talking about it adds anything to it very much. I suppose with conceptual art, where the idea is in the mind of the viewer rather than in the object itself, talking about that becomes part of the art, but that’s a different thing. But even with conceptual art, great conceptual art is something you should get immediately, like a great joke. You just go “Wow, I love that.” Like a Carl Andre—you kind of go “Fuck off!” straight away. It’s brilliant! But I don’t think you need anything in the middle, and that’s where the words occur.

I used to watch Top of the Pops and a song would come on and we’d go “Shit!” or “Beauty!” You weren’t allowed to say “Umm, OK.” You’d have to either say shit or brilliant, and I think that’s a really good way of looking at things. You discard or you engage and you don’t have anything in between.

SB: Do you think there will ever be a return to formalism as the mainstream form of expression?

DH: Of course. It happens all the time. I mean, society used to radically change in different ways, but what happens today, which never used to, is that we savagely regurgitate and devour the past. We’re stealing from everywhere and everything, so we end up with a society that is totally multifaceted and then we have to make art that’s a reflection of that, of a multifaceted society. You’re probably getting aspects of formalism occurring every 25 minutes in some artist’s work somewhere. The thing that is increasingly common is how distracted and diverse everybody is, so you get a figurative painter hanging out with someone who paints monochromes and a conceptual artist, and you all do a show together. They’re all getting on in the same way because they’re all finding aspects of their work in society. Whereas it used to be much more in chronological movements. I don’t think that happens anymore…

You can get an abstract painter who paints portraits, does word paintings and decides he’s doing neons every now and again, and that never used to happen either, but I think it’s great that we live in that world. If you’re not doing that, you’re not able to make art that’s a reflection of the world we live in.

SB: What was your eureka moment when you were a struggling artist? Was it to do with the creation of The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living or something else?

DH: I think it was the spot paintings really for me, because I was a messy painter before then. I loved ’50s abstraction. I love Pollock and Rothko and de Kooning and those sorts of artists, and so I wanted to paint like a gestural painter, but then I was also into minimalism. I wasn’t when I first moved to London. I thought it was all bollocks. I just thought, “It’s not art.” And I thought I was going to change the world and bring it back to 1950s painting or something. I thought that art had lost its way then and I was going to come and save it.

But then I was looking at minimalism and thinking, “Fucking hell, this is really good.” It’s emotional! I remember looking at a Carl Andre piece in Anthony d’Offay Gallery where I worked, these big blocks of wood, and he’d lined them all up and I really loved it. I just got into it and thought, “Fucking hell, it’s actually not nothing, it’s something!” I remember looking at a Donald Judd and seeing the screws lined up, and the colors were pretty good, and I thought it was amazing. I remember thinking, “This is a comment on the world we live in.”

Engineering is everywhere you go. You see all these objects that have a function, and this is one to consider that doesn’t have a function. The spot paintings somehow bridged the gap for me. I still made those color decisions but in a minimal format, and then the end result was so stupidly childish and nursery school—Smarties and sweets and everything—that I just thought it was brilliant. So that was it—the really big thing for me was the first thing I made that I thought was “now”, because before that, everything was nostalgic.