There’s just under one minute left in the first round of the 1999 K-1 Grand Prix Final. Ernesto Hoost goes after his opponent, Andy Hug, viciously, putting him in the corner of the ring, throwing punch after punch—a jab, then a hook, and another hook; then he hits his torso before grabbing him and hitting him with knee strike after vicious knee strike. The crowd at the Tokyo Dome in Japan roars with excitement. Hoost goes on to win and capture the K-1 Grand Prix title.

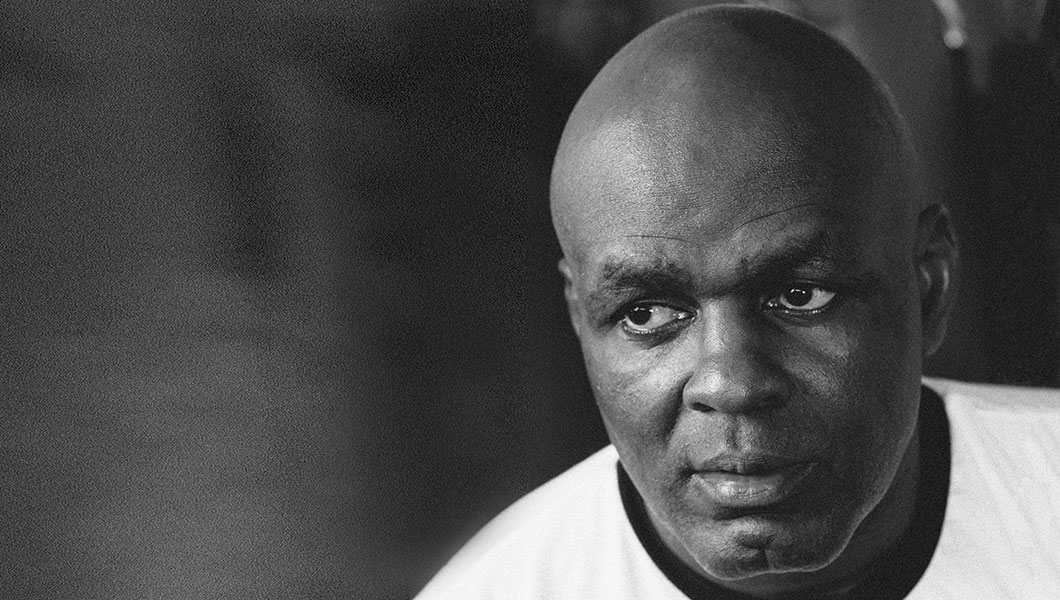

Hoost was one of the scariest fighters to ever step foot inside the ring, like a lion stalking his prey. “I feel at home here; I feel like I have to be in this place,” says the Dutch kickboxer when asked how he feels during a fight. “I would describe it as determined—determined to beat my opponent.”

In Japan, where K-1—a fighting platform that takes its name from kickboxing, karate, kempo, kung-fu and kyokushin—is everything, Hoost was a national hero. He couldn’t go out in public without being recognized—so much so that he wouldn’t go out at all before fights. “We were on TV all the time. We would be on all kinds of different TV programs, so different from what it was like at home in Holland. I couldn’t even go out in the streets before a fight. It was surreal,” he recalls.

Despite holding four K-1 world titles, Hoost’s path to becoming one of kickboxing’s most decorated fighters was one full of obstacles and hurdles. Just a year before his 1999 victory, Hoost, whose success in the ring earned him the nickname Mr. Perfect, was diagnosed with a medical condition that left him unable to fight with the vigor and stamina to which he was accustomed. He fell out of the 1998 K-1 Grand Prix Finals. “I thought that I could still handle everything and I couldn’t,” admits Hoost, speaking from Hoorn, his hometown in the Netherlands.

Hoost didn’t take his defeat in vain. “That made me focus more. Even I myself thought I was finished, but it gave me so much strength,” says Hoost, who credits his comeback in 1999 in part to his daughter’s birth that year. “It woke me up. I think having a child will do that. It gives you purpose; it gave me strength.”

The champion fighter almost missed out on finding his calling in life. After Hoost first discovered kickboxing at age 13, his father would not allow him to pursue the sport. Two years later he got his chance, when kickboxing arrived in his hometown and his father agreed to let him try. The 15-year-old Hoost, who was an active football (soccer) player, immediately signed up. Hoost felt as if he had found his calling after the first three lessons. “It felt really good,” he says. “It felt like I was born for it or something.”

It would be another four years before Hoost would get his first fight, but the wait paid off. Hoost says that the time in between his first lesson and first fight gave him the opportunity to hone his technique. He remembers that first fight in Amsterdam and realizing that his opponent was actually going to try to hurt him. “That made me sharp, and I knocked him out in the second round. I loved the energy of it—it was for me,” says Hoost.

He waited for years before entering the world of professional kickboxing. There was no money in the sport in the ’80s, so after studying economics in school, Hoost took a job as a fitness instructor to young offenders. The job allowed him to train in his spare time, and after eight years he finally made the decision that would turn him into one of the sport’s most legendary champions. “I had to make a decision, either to keep on working or try to be a full professional, and I had to give myself the chance,” he says.

There’s something to be said about the effect of Hoost’s family on his performance. Just as Hoost won a championship after his daughter’s birth, he won another following his son’s. When Hoost was a regular on the fighting circuit, his life consisted of two things: being at home with his family and kickboxing. These days, aside from the regular training seminars he gives, Hoost’s main focus is his two children, whom he recently took to Florida on vacation, where they visited Walt Disney World and the Kennedy Space Center. “I enjoy seeing my children, being happy,” he says. “If they are happy, I’m happy.”

Hoost credits his success and his ability to persevere to discipline. “The most important thing I learned is discipline,” says Hoost. “If you have discipline you can reach a lot—discipline and determination.”

—