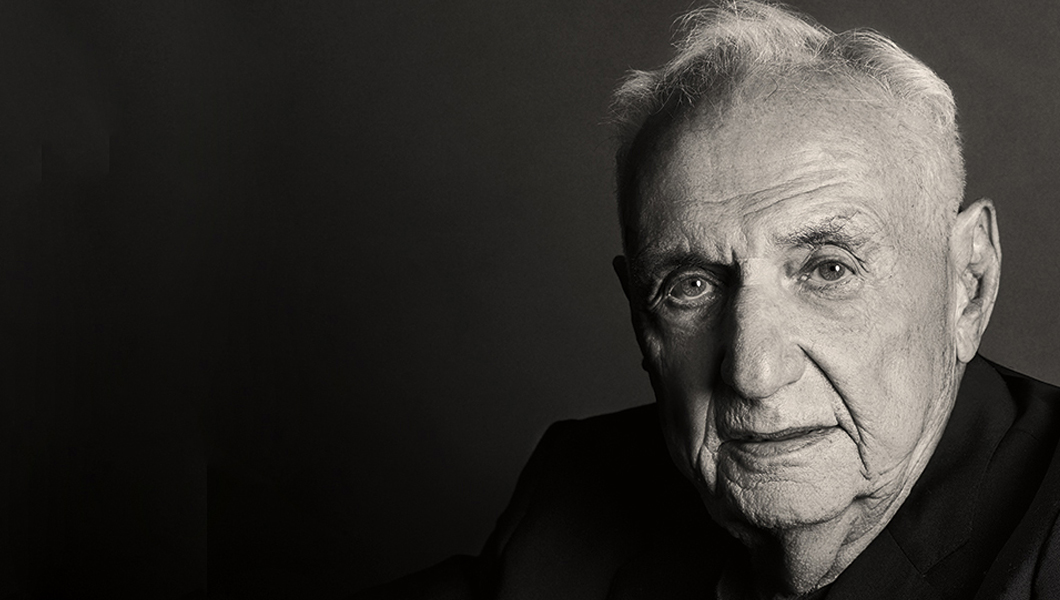

Born and raised in Toronto, Gehry moved to Los Angeles with his family as a teenager and launched his architecture practice there in the early ’60s. Gehry remains based in Los Angeles, but his work is everywhere; in just the last few years, he’s opened prominent museums in Paris and Panama City, and a signature business school building at Sydney, Australia’s University of Technology. Gehry’s buildings are rarely not in the news, as I know from interviewing and writing about him in articles and books for more than three decades. Every time we speak there’s something new to talk about—and it’s always interesting.

Today, at 87, the Pritzker Award-winning architect shows few signs of slowing down.

BARBARA ISENBERG: You’ve been practicing architecture now for more than 50 years. You’ve built important buildings all over the world, won loads of architecture prizes and yet you say there’s a lot of folklore about what you do.

FRANK GEHRY: There is. People say I design from the outside in, and that’s not true. Once I engage with a client, I try things. I try to discover the feeling of the client, what he’s asking for and needs and what I can bring to the table.

BI: At this point in your career, what leads you to take on a project?

FG: I take on projects when I feel comfortable with the client and relationship. I don’t take everything that comes our way. The project also has to be something I’m interested in.

BI: What are you interested in these days?

FG: I’m interested in projects I think have a good social impact. I take on commissions that have to do with art or music or philanthropy and that help to make the world a better place.

BI: Can you give me an example?

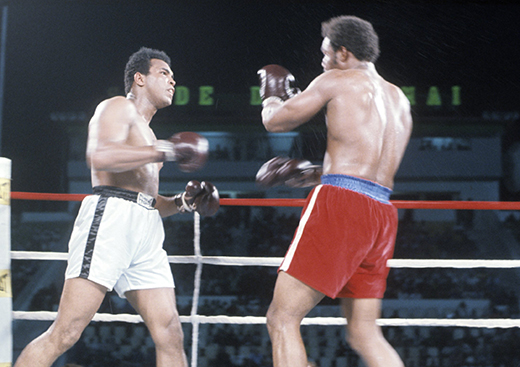

FG: I was recently in Berlin for auditions for Daniel Barenboim’s West-Eastern Divan Orchestra. It’s a youth orchestra, and the musicians come from all over the Middle East. There was an Israeli violinist, a Syrian oboist. They were all playing together, and it brought tears to my eyes. I designed their new concert hall in Berlin, which opens in March, as a gift to them.

BI: So you’re doing more of this sort of work now than in the past?

FG: Probably. Because I can. As I get older, more of the work now is philanthropic for me, although not necessarily for the office. My son Sam, who works with me and is showing talent as an architect, has also worked on some of those projects, like the Children’s Institute campus in Watts and the Jazz Bakery.

BI: What is it like working with Sam?

FG: It’s great working with him. He’s 36, married now, a new father with an 11-month-old daughter. He’s been here about 10 years, watching. I’ve been having fun working with him on a new house for my wife Berta and me, which he’s taken most of the responsibility for and which is almost done.

BI: Do you bounce ideas off Sam as you might your senior staff?

FG: I try not to infringe on his growth, but I pull him in a little. And if I ask him, he doesn’t hem and haw. He usually says something … and sometimes it’s devastating.

BI: Who did you find inspiring when you were a young architect yourself?

FG: Many of my early influences were Japanese, because so many of my teachers at the University of Southern California were GIs who were returning from Japan. The wood style of that time is in my DNA. I loved Harwell Harris and Frank Lloyd Wright. I didn’t like Frank Lloyd Wright’s politics, and so although I had three opportunities to meet him, I didn’t, and I regret it. When I got to Harvard Graduate School of Design, I learned a great deal about Le Corbusier. I had been so focused on Japan because of USC, and Corbusier’s work convinced me to go to Europe and look around. Corb is number one on my hit parade.

BI: You’ve also spent considerable time with Los Angeles artists. Could we discuss the influence of those artists when you were starting out in the ’60s?

FG: They were really important to me, and I understand it more now than I did then. When I got out of architecture school, I did [the graphic designer] Lou Danziger’s house and studio in West Hollywood, and I got a lot of flak from practicing architects here. This and that were wrong. So I felt alienated.

It was different with the artists. When I went to the Danziger site one day, the artist Ed Moses was wandering around, and he’s a friendly guy. He was very complimentary and came back with some of his artist friends. Later, I went to see his shows. I also went to shows of other artists in that group: Richard Diebenkorn, Billy Al Bengston, Sam Francis, Alexis Smith, Michael Asher. They liked me, and I felt honored to be in their presence.

BI: What did you learn from them?

FG: I learned an ability to take risks, to get an idea and to follow it through.

BI: How was the artist’s approach different from the architect’s approach?

FG: It was the immediacy of it. The results are quicker. The artists would talk about a painting, and a few days later it was done. With architecture, you have to work everything out. There are lots of legal issues and moving parts. Architecture takes longer. You come up with an idea and it takes a year to be built. And the bigger the buildings get, the longer the process.

BI: What do you do to decompress?

FG: I go sailing. Sailing is something I accidentlly became interested in a long time ago. I fell in love with it. I would go sailing with whoever asked me. Then, years later, I bought a boat.

BI: What is it about sailing? What’s the feeling?

FG: It’s quiet. You have to know what you’re doing. You have to focus on the mechanics of it, and it’s different every time. The wind is slightly different. So are the conditions of the sea. It can be overcast, sunny, foggy. You get into all kinds of problems, and you have to be aware. The aesthetic of it is beautiful.

BI: You recently designed a boat yourself.

FG: Yes. People call me to do all sorts of stuff, and I like it. I’m open to things, and I’m curious.

BI: You often talk about the importance of curiosity.

FG: Curiosity came to me through discussing the Talmud with my grandfather. The Talmud starts with the question “Why?” It’s all about challenging and searching and wondering and asking questions. My upbringing and Jewish training exposed me to the Talmud, and I would talk about it with my grandfather when I’d help out in his hardware store. What you learn from the Talmud is a willingness to entertain change, and change is inevitable.

BI: Actually, both your grandparents had a great impact on you when you were a boy growing up in Toronto. You’ve told me in the past about how remembering the fun you had building things with your grandmother later nudged you toward architecture as a career.

FG: When I was a kid of 7 or 8, I would go around with my grandmother to shops to get wood scraps for the stove. The scraps came in burlap sacks, and every once in a while, when we got home, she would empty the sacks on the kitchen floor. Then we’d sit on the floor together and build stuff—bridges, cities, buildings—and she’d talk with me about it. She was from Lodz, Poland, where she ran a foundry, so she had some stripes in building things. It was something she knew, and it was so much fun for me.

BI: Now a grandparent yourself, you’re taking on a whole new challenge: the Los Angeles River. Why did you take on such a huge project at this point in your life?

FG: Our mayor asked me to do it, and he sent some emissaries who said the city of New York built the High Line, which is getting a lot of play, and Los Angeles should be able to capitalize on its river and become a destination. I said the High Line was a rusting railroad bridge they put plants on, and it was fun and nice, but the river is a flood control project so it has its own mandate. I said if they would clear a path for me and protect me from all the people who have been working on the river for the last 20 years and are going to claim that I’m an interloper on their territory, I would take it on and study it pro bono, which I’ve done.

BI: Do you think of it as your legacy for Los Angeles?

FG: No. I don’t think of it like that. I don’t presume to be anything more than a facilitator. We’re letting a billion gallons of water go out of the river into the ocean that should be captured and cleaned and reused so we can lower our purchases of water by a significant amount of money. There are public health and other significant issues yet to be dealt with and solved, and they would pay for themselves in the long run.

BI: You’re 87 now. Do your projects ever get easier?

FG: I haven’t made it easier on myself. I’m still on that quest for visual answers. I’m still seeking the way to put inert materials together and evoke lasting feelings.

BI: Are there advantages to being older?

FG: The advantage of being older is that if you’re still standing and working and doing significant work, you get more credibility. You also have a clearer picture of what’s going on around you, and you understand the futility of trying to harness it all into the great cause for humanity.

BI: Yet you remain optimistic.

FG: If I wasn’t optimistic, I’d stop working. You see small victories that keep you alive. You make headway here and there. You’re not in a vacuum; there’s creative activity on many topics, which creates an exciting environment that’s engaging and keeps you interested. You see a lot of progress in many areas of society, which you always hope will prevail, and the world will continue to become a better and better place to be.

BI: Does that optimism explain your passion for Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote and Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland?

FG: I love them. They are both on my nightstand.

BI: Because?

FG: Because they are telling us about the frailties of human nature and the joy, fun and nuttiness of it. We are all living like that. Most of our lives are more crazy than Don Quixote’s. Cervantes nailed us.

Barbara Isenberg is the author of the Los Angeles Times best-seller Conversations with Frank Gehry.

—