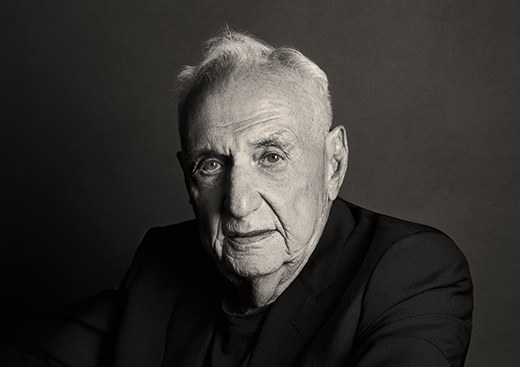

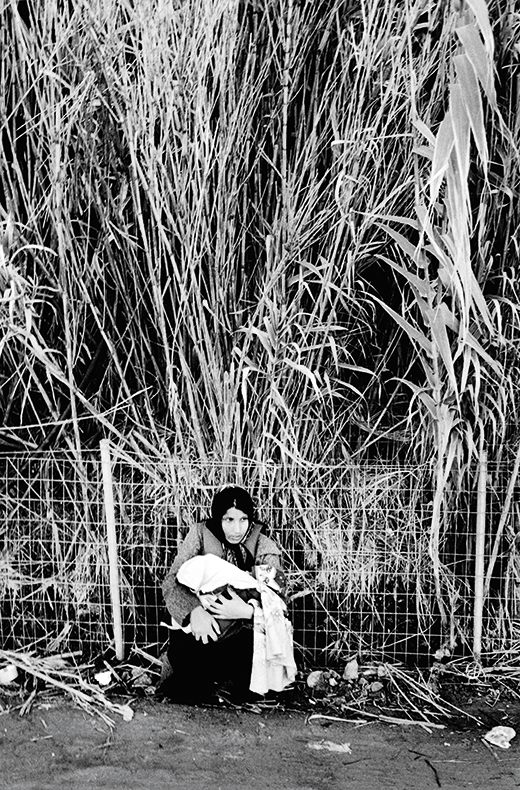

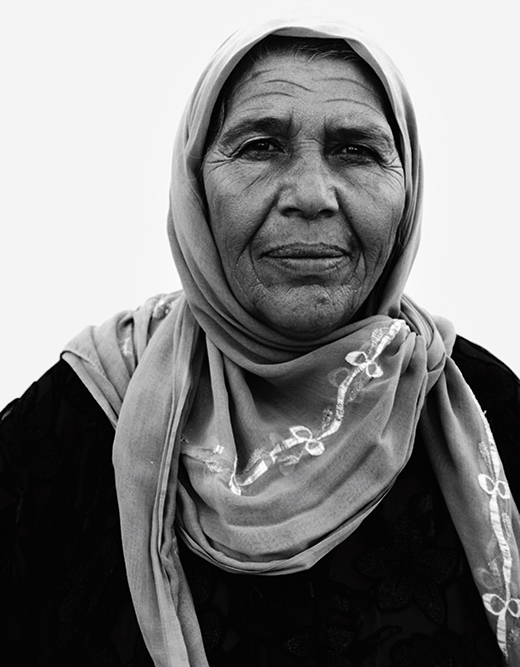

I met Giles Duley the day he introduced me to Khouloud, a Syrian refugee mother paralyzed from the neck down after being shot by a sniper, who lives in a small tent in a refugee camp in Lebanon with her loving husband and devoted children. I know that anyone meeting her would completely change how they think and feel about Syrian people and refugees. Few people will have the chance to meet her in person, but Giles’s photography introduces her to the world.

Different photographers can use the same camera or light, or all shoot the same frame. But what is different is the soul of the person behind the lens, and the moments they recognize and are drawn to—the emotional connection they make. That is what I love about Giles’s photography. Looking at his images, we can feel what he feels. It’s clear that he connects deeply to the human condition of people from all over the world. He himself has been through an ordeal. They say that adversity helps grow compassion, and Giles’s art certainly seems to bear that out.

ANGELINA JOLIE: You describe yourself as a “storyteller”—what is it about the nature and power of stories that inspires you?

GILES DULEY: Stories have incredible power. I don’t truly understand, but they have a mojo, a magic that helps us to comprehend the world and others. Since the birth of humankind we have been telling stories to each other; from campfires, cave paintings, books and film, storytelling is central to our culture and being. I follow in that tradition. I’m not a journalist—I don’t focus on facts and figures. I’m interested in our shared humanity, our empathy for others and the details in life that help us to connect.

AJ: You tell stories to change the perceptions and emotions of your audience, but do you find that they change you as well?

GD: My story lives in the stories of others. This work is my life, so of course it deeply affects you. Many of those whose lives I document I’ve known for years; they are my friends, and sometimes I struggle to sleep knowing where they are and feeling I haven’t done enough. But this work also gives my life so much; the experiences and friendships have brought me laughter and tears, and I have received far more than I have given.

AJ: After a year covering the refugee crisis from Europe to the Middle East, what have you learned that you were perhaps not expecting?

GD: I have covered the effects of conflict on civilians across the world for over a decade; what I didn’t expect was to be covering those stories in Europe. It’s maybe an obvious thing to say, but being in Lesvos, meeting Afghanis, Syrians, Iraqis who were fleeing wars I know all to well—to see them landing on the shores of Europe I realized how small and interconnected our world really is. What shocked me the most was Europe’s response to the crisis, or rather lack of it. It was shameful.

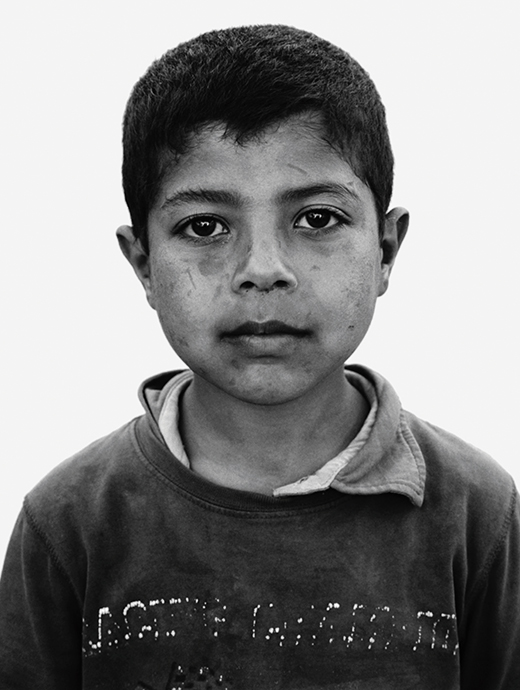

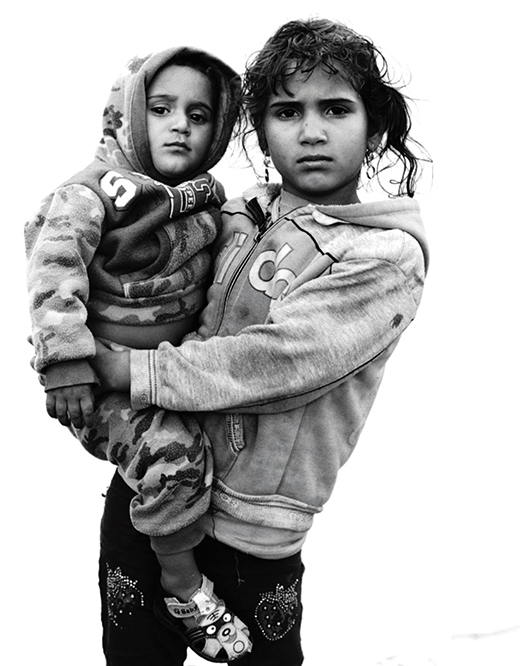

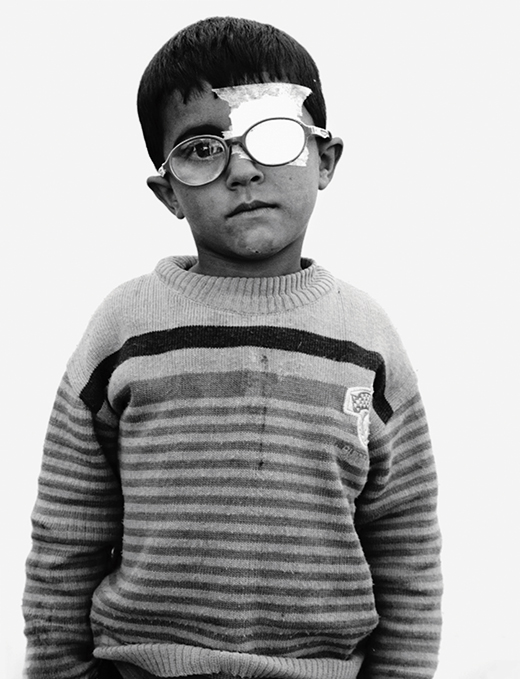

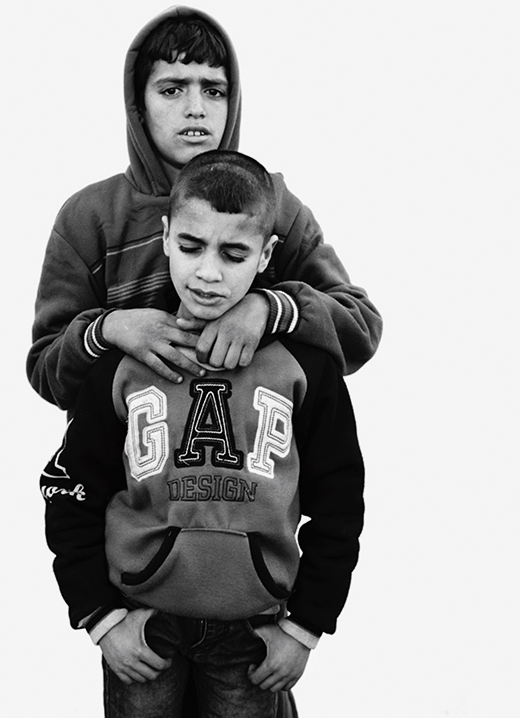

AJ: Your photography has raw emotional force. You show people as they are, not as they are labeled by the world. Your subjects are not “victims” or “refugees” but people just like us. Why is it so important to you to show the humanity of families affected by conflict?

GD: It was never anything I considered or thought through; it just came naturally to the way I work. I see everybody the same, whatever your status, whatever your religion, your country; I see a shared humanity. Wherever I go, people’s hopes and dreams are the same; to see their families protected, their children educated, their loved ones treated when sick. In a sense my camera is completely democratic—it doesn’t judge or label, it sees all people equally.

AJ: How has your own experience of adversity affected your creativity?

GD: My accident changed everything. For over a year in hospital I was told I would probably never work again or live independently; nobody believed I would be able to return to work again. But early on I made a decision; I decided I would never focus on what I couldn’t do. Instead I would focus on what I could, and excel at that.

So of course I am severely limited as a photographer by my injuries. I can’t move quickly, kneel down, climb on something for a better view. I get tired and I live in pain. But I don’t think about that. What I focus on is the fact that despite all that I can still take photographs and do the work that I love. And for my injuries, my empathy and connection with people has grown—and that outweighs the bad. I can honestly say that since my accident I am stronger, more focused and a better man and photographer.

AJ: I know that you often go back to visit families you have photographed, sometimes many times. Does the fact that so little has changed, that they are stranded in refugee camps or informal settlements with dwindling amounts of food and money, ever shake your faith in your calling? What keeps you going in those darker moments?

GD: If you believe in a story, you have to keep telling it. Eventually somebody will listen. Too often we in the media are guilty of always moving on to the “next” story. If things haven’t changed for a family or community, I think it’s my job to keep telling it. But of course that can get you down. To go back, to see somebody living in the same terrible conditions, it makes me feel like I have failed.

Khouloud’s story was exactly like that. When I first visited her in 2014, she was so vulnerable and in need of support. So when I discovered she was still living in the same makeshift tent two years later I felt sick in my stomach. I thought “What’s the point of telling stories if it doesn’t change lives?” I went to see Khouloud and her family and I actually burst into tears when I saw her. For over two years she had not moved from her bed, in a tiny room that had no windows. It was like torture and yet she was still smiling. My first words to her were “I’ve failed you.”

After some time, though, I thought of my own words: “If you believe in a story, keep telling it.” So I did. I tried to document every part of that family’s story, to do it better than before.

Just a few months ago an organization in the U.S. called Random Acts contacted me. They had seen the story and they wanted to act. We worked on a crowdfunding campaign together and in the end people from over 100 countries donated close to $250,000 for Khouloud and three other refugee families living in Lebanon. That’s the power of a story. That is why I do what I do, and I will keep telling stories till people listen. I don’t think a photograph can change the world. However, I do believe it has the power to inspire the people who can.

AJ: Why has so little changed? What are we getting wrong? If you had the ability to influence the foreign policy of the U.S. and the other powerful nations, what would you change in relation to their policies on the refugee crisis?

GD: The refugee crisis is a global problem and it needs a global solution. Most politicians have been reactionary rather than visionary in their approach. Until world leaders work together and create a long-term plan to tackle the root causes, the crisis will continue. Sadly I can’t see that happening and instead we are seeing the continued use of negative and fearful rhetoric by politicians. If I could do one thing? I would take every politician to visit the families I document. Of course I can’t do that, so I will continue to strive in bringing the stories to them.

AJ: You have spoken of your hope that your photography will inspire people to act, to do whatever they can to help address the refugee crisis, from giving money to lobbying their governments and helping in their communities. Is one of your aims to counter the sense of powerlessness people can feel in the face of relentless negative coverage about refugees?

GD: The refugee crisis can be overwhelming for people. Faced with the sheer numbers and scale, again and again people say to me “But what can I do?” And when faced with the negativity and hate seen on social media, in the press and in the words of politicians, that sense of helplessness grows. But I believe we all can and should make a difference. I believe we will look back at this time as a turning point in the history of our humanity; do we choose to turn our backs on those in need or open our arms? It is for those who know what is right to stand up and be counted and not be silenced. We can support grassroots organizations who are helping refugees directly, raise money for organizations such as the UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner of Refugees), write to politicians, speak up on social media when we see hate speech. We can’t change the world on our own, but that mustn’t stop us doing what we can. If we all do what we can, then the world will change.

AJ: You recently described a woman in Finland telling you about her community’s efforts to help Syrian refugees, saying, “It’s better to light a candle than to curse darkness.” It seems the same could be said about your photography. Is that a fair characterization?

GD: In 2015, one hundred refugees and asylum seekers were temporarily housed in the small Finnish island community of Nagu. It was a decision that not all welcomed, and most had their doubts. In Nagu they are a small, close-knit community and during the winter months have few visitors. They had worried about bored young men, of attacks on women and how would these Muslims integrate with their customs?

But the community made a decision—they would not treat these families from Iraq and Afghanistan as refugees. Instead they would treat them as guests. The warm welcome did make a difference, but the benefits have not just been felt by the refugees. Despite their initial reservations, the people of Nagu now feel it is the refugees that have brought them something.

One of the islanders, Mona Hemmer, described their philosophy to me. “It’s better to light a candle than to curse darkness.”

I don’t know if that phrase reflects my work, but I certainly aspire to that. In the darkest places you discover light; through my work I get to see the best in people, to witness the strength of family and to see true love. It’s in those places that I choose to focus my work, because we see humanity and hope. Many photographers want to show the differences between us; I want to show the similarities. Despite showing the stark reality, I hope my photographs also give hope.

—

LEGACY OF WAR

Legacy of War is a five-year photographic project exploring the long-term effects of conflict globally. Most specifically, Legacy of War documents the lasting impact of war on individuals and communities, told through the stories of those living in its aftermath.

With the mainstream media firmly focused on the short-term economic and political consequences of conflict, LoW is concerned with the human and the personal. It explores the local landscapes and everyday lives of those affected by conflict—often decades after peace treaties have been signed—and raises issues that are often neglected by mainstream news and history.

For more information, visit legacyofwar.com.