WALKING AROUND IRVING BLUM’S HOME IN BEL AIR FEELS MUCH LIKE DYING AND WAKING UP IN 20TH-CENTURY ART HEAVEN.

In the living room, a Bauhaus sculpture sits across from a Jasper Johns watercolor and an Ellsworth Kelly two-panel, in a room whose lofty ceiling only barely contains the reputations of the artists it shelters. Undoubtedly, though, the room is dominated by two items, masterpieces of pop art: a giant Warhol painting facing a giant Lichtenstein, placed very deliberately together, in memory of the two artists with whom Blum is perhaps most famously associated.

Irving Blum, now 86 but seeming 20 years younger, moved from New York to Los Angeles in 1957 and bought into Ferus, the tiny gallery in Los Angeles synonymous with the emergence of L.A. artists like Ed Ruscha, Wallace Berman, Dennis Hopper and Ed Moses. But it is perhaps best known for hosting the West Coast debut of pop art, a moment credited entirely to Blum.

Blum had visited Andy Warhol’s studio in 1961 and noticed a number of large cartoon-style paintings that Warhol, a former illustrator for shoe companies, was working on. “I didn’t like them,” Blum says. “I didn’t think they were very interesting. But I liked him.” Several months later he went back to New York and visited Leo Castelli, the influential dealer who straddled the abstract expressionist and pop art movements and who was a mentor to Blum. Ivan Karp, a young man who was working for Castelli and would later become one of the leading champions of pop art, showed Blum some transparencies—cartoon renderings of very sad, tearful girls. “I looked at them and said, ‘Andy Warhol?’ Ivan said, ‘No, a guy who lives in New Jersey. His name is Roy Lichtenstein.’ I had a connection with Roy’s work. He had that black outline—it reminded me of Leger somehow. And I said, ‘These are interesting. I’d like to show him.’ ”

Blum called Warhol and went to see him. “As I walked into his little house on Lexington Avenue, I saw there were three soup can [paintings]. I asked, ‘What happened to the cartoons?’ He said, ‘Oh, I saw a work by an artist at Castelli’s, a guy doing cartoons. Maybe doing them better than I was doing them. In any case, I’m doing these soup cans now.’ I took a leap and said, ‘What about showing ’em in California?’ ” Warhol was unsure, as all his friends lived in New York. But Blum remembered seeing a torn-out magazine photograph of Marilyn Monroe stuck to the wall with pins as he walked into the studio. “I knew he was starstruck, and so I said, ‘Andy, movie stars are coming to my gallery.’ Andy said, ‘Let’s do it.’ ”

After the show, Blum installed the entire Campbell’s Soup Cans series in his little apartment on Fountain Avenue. “It was as if I was sitting in a room with a masterpiece by Picasso,” he says. “I just thought they were really important. I had an overwhelming feeling about them. People thought I was quite mad but I thought that they were unbelievably valuable.” Only five had sold at the show, for $100 each, so Blum bought them back so as to keep the collection together, as per Warhol’s request. “I called him and I said, ‘Andy, I’ve got them all.’ He said, ‘Great,’ and I said, ‘How much money to buy them all?’ He said, ‘$1,000.’ For all of them. I said, ‘How long will you give me to pay?’ He said, ‘How long do you want?’ I said, ‘I want a year.’ He said, ‘I’ll give you a year.’ I sent him $100 a month for 10 months.”

They now belong to the Museum of Modern Art and have a cultural importance that is priceless. Says Blum, “I was really, right from the beginning, just exploring my own taste and staying, insofar as I was able, consistent to that. There was never a lot of business and that never mattered a great deal to me. I had to survive, but so long as I was able to do that I followed my own instinct.”

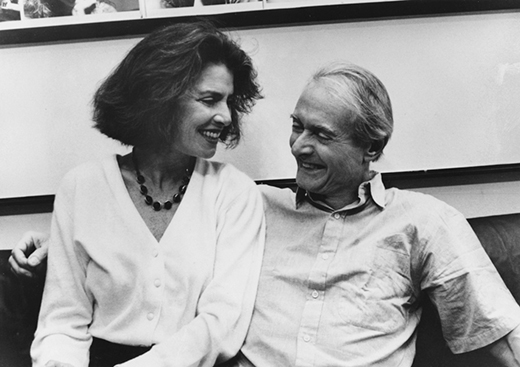

Among the contemporary masterpieces also sits a small framed black-and-white photo of a young, very dapper Blum with mod queen Peggy Moffitt and a bevy of 1960s beauties. Times were different then. Headier, perhaps. The art business was in its nascency, and pop art was the rebellious answer to the heavy intellectualism of abstract expressionism, the very first American fine art movement. Today, Blum avoids most of the art fairs, except Basel in Switzerland—the Miami edition is “wonderful” but there are too many distractions from the art itself, he says.

He points out a small, unassuming piece around the corner from the Warhol—it is the first painting he ever bought, an Ellsworth Kelly he purchased from the then-unknown artist in 1957. “I saw a number of things by him including this and I liked everything I saw, but this was small and I knew I could afford it. Or I thought I was able to afford it, and it’s a kind of plant shape. He sold it to me and there it is.” Kelly, who passed away just a few weeks before our tour of Blum’s house, would become one of his dearest and greatest friends and possessed that special quality that only true artists have. “It has to do with a certain kind of poetry, but it’s hard to define,” says Blum. Small and unassuming, that Ellsworth Kelly painting is, like everything else in Irving Blum’s living room, an important marker—not just in Blum’s own remarkable life story but in the story of American fine art itself.

—