HUMANITY: Where do you think you learned to be who you are? Your compassion, your empathy—how did you learn to be who you’ve become?

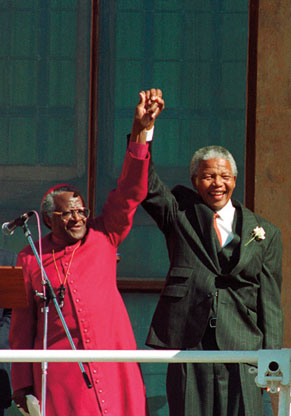

DESMOND TUTU: It’s a very good thing to be aware that you owe so much to other people. What you become is the influence of so many. I say the major influence of my life as I look back was my mother, who was not terribly educated; she finished elementary school and then went to a trade school to get a diploma in domestic science. I say to people that I resemble her physically. She had a large nose like mine and was thumpy, but I say I hope I resemble her in who she was. She was a very compassionate and caring person and couldn’t stand someone having an injustice done to them. She would very gently try to be on the side of the one who was having the rough time. You don’t consciously say you are emulating somebody, but in fact it is someone that has left a stamp of their personality on you. There was a very famous English priest; I had TB and I was in the hospital for 20 months, and amazingly, this man, who used to be very busy in Sophiatown, just outside Johannesburg, would visit me every week when he was available. When he was not available he would send another of his brethren. And so I am clear that so many people have touched my life and helped me to become a slightly better person than I’d otherwise have been, and to have had the wonderful support of my wife, Leah, in the days that we were struggling during apartheid. It was rough for her and for the children. Sometimes the apartheid government would target my wife. I have to take my hat off to Leah and to the children in the way that they were there with and for me in a very difficult time in my career. And so I hope that I’ve been able to contribute in helping us all to become slightly better people. Our country, which was being crushed under the burden of the vicious policy, the racist policy—I was part of a huge movement in the country and internationally, the anti-apartheid movement, hoping that it would be part of a process of helping all of us become slightly more human. We become better people by being caring people. You discover that as you give, in fact, you receive much more than you put out. And it’s been wonderful to be there when the struggle against injustice was won in our country, and all of us, black and white in South Africa, tasted what it meant to be truly free in a democratic dispensation where you didn’t have silly rules that depended on the color of a person’s skin. You learned that our value doesn’t depend on biological irrelevancies, really. We are born really to be compassionate people, to be caring people. You have a billion people living in absolute poverty, having so many people go to bed hungry; you have children dying of preventable diseases just because their families can’t afford fairly inexpensive inoculations against measles, against smallpox; and then to be appalled by how we spend so much of our money on arms! I mean, it’s obscene to know the billions and billions that we invest in these ghastly instruments of killing when we know that a small fraction of that would ensure that no child would die because they didn’t have clean water to drink, no child would die because they didn’t have affordable health care, no child would languish because they didn’t manage to go to school.

HUMANITY: You’ve accomplished so much in your life—what continues to motivate you?

DT: Well, in terms of accomplishment, it’s a wonderful thing to be part of a coalition, being part of a movement, and I had the privilege of being regarded as one of the leaders in the movement for justice, but we haven’t reached nirvana yet. There are so many parts of the world where you hope you can make a contribution. You get shocked when you see people scavenging in dustbins, and that should not be happening in our world. We have the capacity of ensuring that no one would have a rough time, that everyone would have a decent standard of living. There are many people in the world who are seeking to work for that, and I hope I can continue to be part of that kind of movement. People who say “Let us make poverty history.” People who say “Let us end war.” People who say “Let us stop producing nuclear weapons. Let us stop war. Stop war, make love,” you know? That’s God’s dream for all of us. In my own country, South Africa, we have got something that we didn’t enjoy for a long time—I mean freedom—but look around and you see many of our people languishing in poverty, especially young people who are unemployed, and we are sitting on a powder keg with so many people poor, and they see others who are not poor, and it’s not sustainable. The inequities are not sustainable. I mean, we don’t need to be a world that feels so vulnerable, so insecure, worrying about terrorists and that kind of thing. You don’t need an agitator to tell you that it is not right, and we have the solution in our hands, which is to want for the other what you desire for yourself.

HUMANITY: How would you hope to be remembered by the world, and then how would you like to be remembered by your family and those close to you?

DT: I’ve thought about this. Sometimes they ask you what you would want for your epitaph and I would say I would hope everyone would remember me as someone who loved. Loved … I love you. As someone who laughed and someone who cried, because I do all three, yeah. I would hope that is what they would remember.

HUMANITY: What is your idea of true happiness?

DT: I hope that all of us can get persuaded that, actually, my humanity is bound up with your humanity. The more foolish human you are, the more likely that I will be too, because we will be living in this wonderful delicate network of interdependence. I hope that many of us will come around to realizing that we can’t be fully human when there are so many who are being dehumanized, made less than who they really are. Whether we like it or not, in that particular process, we do become less than what we could really be. When you see someone picking at a rubbish bin or a rubbish dump you ask yourself a very deep question—if that thing doesn’t somehow, apart from appalling you, somehow diminish you. There may be a lot of us who say “Oh no, it’s got nothing to do with me.” But that is not true. Something of my humanity is lost as that person is dehumanized by conditions that you and I know can be eradicated. I just hope that we will come to realize just how precious each one of us is.

HUMANITY: What do you think most of the world’s leaders are lacking right now?

DT: Most are wonderful people. They get to be constrained by all kinds of considerations. If all of them said: “I know I’m no longer up for re-election, so I’m going to do the things that I know ought to be done. I’m going to do the things that are going to contribute to peace efforts in the world. I’m not going to invest any more in arms. I’m going to invest more in people, in homes, the humanity of people. I’m going to invest in schooling. I’m going to invest in things that help neighborhoods to flourish. I’m going to invest.” I mean, it seems so obvious, but I would say to all the leaders, “How about trying to help fulfill the idea that we are all members of one family?”

HUMANITY: Can perfection be achieved?

DT: Not this side of death, I don’t think. I mean, very, very, very few, but it is not so much the goal that matters, it is the going, the getting there. Being involved and saying, “I want to be a more compassionate person, I want to be a more caring person,” and striving after that. No one is such a pain in the neck as someone who is on a crusade. Good people that we know are almost always people who attract, like Mother Teresa, Mahatma Gandhi, you name it. People who would bring a smile to your face as you think of them and who make you want to be a better person. They might be on a crusade, but they are not crusaders. They are beautiful people. Archbishop Hélder Câmara is famously quoted as saying: “When I feed the hungry, they say I’m a saint. When I ask why are they hungry, then they say I’m a communist.” He was a fantastic Roman Catholic archbishop. Archbishops always wear splendid robes; he wore khakis. Archbishops usually live in residences called palaces because they are very sumptuous places; he refused to live in one of those and chose to live in a favela. I visited him and you could see that he had stolen the hearts of all the people. But the story I want to tell you is that we were in a meeting once—Mother Teresa was present, he was present. I also was privileged to be present in Paris and I went up to him and said, “Please, can you bless me?” and I knelt down in front of him. He almost immediately plunked down himself and said, “OK, let’s bless each other.” A good person makes others comfortable in their skin, helps them want to be better human beings.

HUMANITY: What would you say to a young person who wants to follow in your footsteps and make an impact in the world as you have?

DT: We oldies become cynical. You young people dream that the world can become a better place, and so I usually say to them, “Go on dreaming. Go on being idealistic. Don’t allow oldies to make you cynical.” And so, if a young person wants to ask me, I say dream, dream, dream. Dream and just go on dreaming and dream that you will be helping God to make this a better world.

HUMANITY: Over the course of your career, you achieved quite a level of notoriety. Were there any surprises or negatives about becoming so well known?

DT: It’s OK when it helps you to help other people. I think I’m vain, but it’s wonderful to have a wife like Leah who really pulls you down a few pegs when you think you are very [important]. We went to West Point Military Academy, and at the end the cadets said, “Here is a cap for a memento,” and I tried it on and it didn’t fit me. Now, a nice wife would have said: “Oh, the cap is too small.” She said: “His head is too big.” And more recently she found a bumper-sticker kind of thing, which said: “You are entitled to your wrong opinion.” So I have someone readily available to puncture my balloon, you know. She’s wonderful—very good for me.

HUMANITY: What was it like receiving a Nobel Prize?

DT: I mean, it was very important. You say certain things before you get the Nobel Peace Prize, then you get a Nobel Peace Prize and you repeat the things that you said when nobody paid attention and suddenly it’s as if an oracle is speaking. But it was a prize given to me representatively. It was a prize they wanted to give to all of those who were involved under the anti-apartheid struggle. They couldn’t give it to everyone, so they thought, “He’s an easy name, Tutu. It’s easily recognizable.” But it was fantastic at the time and it’s an amazing thing. On the eve, I think the eve or maybe it was the same day, you’re in Oslo in this hotel, and you stand on the balcony in the evening. It’s a fantastic candlelight procession to honor you and it seems to go on forever and ever, with the candles flickering in the dusk. Yeah, just a fantastic experience, a fantastic honor.

—