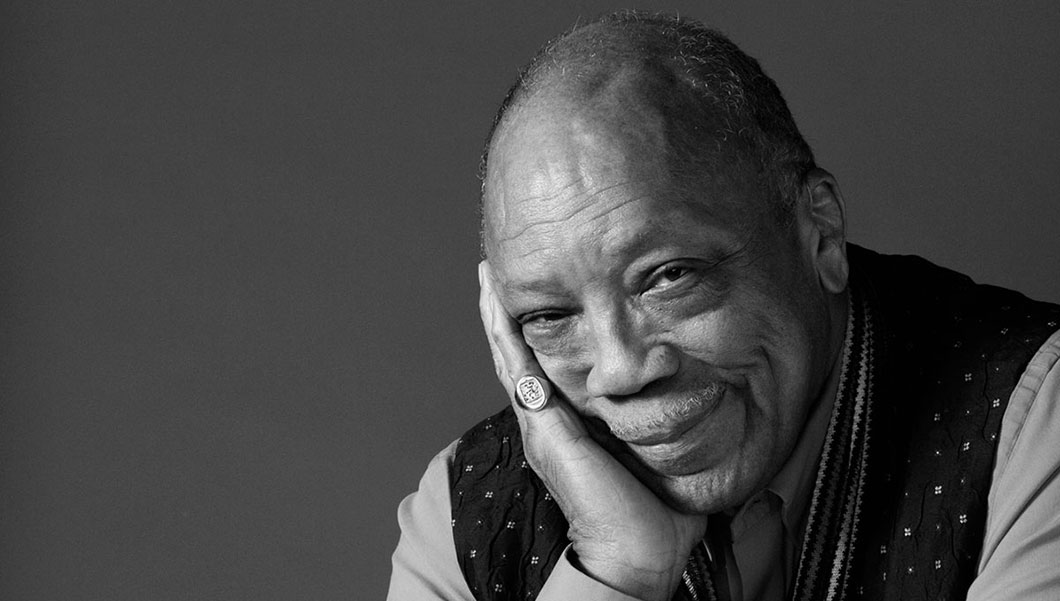

Sunny Levine was born into music royalty. He’s the grandson of the legendary Quincy Jones, who’s worked with everyone from Ray Charles to Frank Sinatra, Miles Davis to Michael Jackson. Though Sunny has forged his own path as a producer and artist, the L.A. native has always known where to turn first for advice. In an unparalleled career spanning almost seven decades, Jones has left his mark on the music world not only as a producer, composer, musician and songwriter but as a trailblazer in transcending racial barriers, too. A dedicated humanitarian committed to social justice, Jones was the first African-American to become VP of a major music label and to write major motion-picture film scores—all while enduring criticism for his three interracial marriages, the first of which was to Sunny’s grandmother. But above all else, in Sunny’s eyes, Jones has just always been a grandfather—one with enormous shoes to fill…

My granddad’s a funny cat. He’s not your average grandfather. I don’t think I’ve ever been to a movie with him or the park or a ball game. Even when I was younger he told me to call him GP, short for grandpa. He still calls me GS, for grandson. Now that he’s a great-grandfather, he tells my niece, “Call me GG.”

My grandmother, Jeri Caldwell, was his high school sweetheart and first of three wives; they met in Seattle and then moved to New York together, so she was there from the beginning of everything, since he was a teenager. My mother, Jolie, is their only child. They divorced when she was about 8.

I was born in L.A. in 1979. We moved to upstate New York a few years later to sort of get away from disco and L.A. It was getting weird. My first real memory of my grandfather is of him visiting us in upstate New York, in the snow. It wasn’t of him being a superstar producer. Then we moved to England when I was 4 and we’d see my grandpa once in a while, but I really got to know him when we moved back to Los Angeles when I was about 7 or 8. He was getting divorced [from Peggy Lipton] and he was living at Hotel Bel-Air at the time. We’d go there and hang out or take walks.

My grandfather started making Michael Jackson’s Bad right after we got back from England. We lived right by the studio where they did it and would go by all the time after school. I was a huge Michael Jackson fan, and I remember they had really good food and candy at the studio. It was pretty wild. I wasn’t totally aware of just how famous he was.

Somewhere around that time he got a house and it became the epicenter of where we would all hang out, go swimming, play basketball. There was a lot of life and I felt like all the kids were kind of the same age. I am the second grandchild (my brother is the first). There were no other grandkids until I was 16, but my aunts [Rashida Jones and Kidada Jones] were around my age.

I vividly remember one night a crazy dinner party going on at his house when we stopped by. Lionel Richie and all these people that I actually knew were sitting there. Then there was this dirty, weird white guy. I asked my mom, “Who’s that dirty guy?” She said, “That’s Bob Dylan!” I didn’t even know who Bob Dylan was at the time.

I’ve been making records since I was 14 and I’m 37 now, but never along the way have all the floodgates been opened for me; he doesn’t believe in that. However, I do turn to him for different kinds of advice. I wish I had a little bit more of my grandfather’s ability to just put big things together and make them happen, and his confidence and bullish way where he’s just like, “We’re going to do this and it’s going to get done,” and then it happens. He is just so good at putting things together—putting people together, putting deals together, and seeing all sides of things. He just makes these grandiose records that are so dialed in and so worked out and perfect.

After everything my grandfather did as a big-band arranger and having big bands, making records, producing records and working with some of the biggest names in music in the early ’60s, he started doing film-score work. That was a big deal. There were no black people in that world. So I feel like that was the biggest jump, where he was like, “Alright. I’m doing this,” and got in that door and did big movies. He seemed almost defiant about it, like, “Why can’t I do that?” I think that’s a big part of his whole career and trajectory. People say, “You can’t do that, you can’t pull that off,” and he’s like, “Yeah, I can. Why not?”

Ten years ago he put on a concert in Rome that was called We Are the Future to raise money for charity to build schools in Africa. They were trying to write a song like a new “We Are the World,” which he produced in 1985. My granddad was like, “Why don’t you try to write a song for this thing?” I was like, “Really?” He had heard what I’d done but I didn’t think he believed in me that much. So I went away and wrote these songs and I brought one back. He was like, “That’s cool. Go do another one.” Then I came back the next day with another song and he was like, “That’s it. That’s great.” He was like, “Go see Rod [Temperton] tomorrow and you guys work that up and get some new parts in it.” Rod wrote all the Michael Jackson songs, like “Always and Forever.” So we worked on the song and then we went to Rome and performed it and recorded it. It was really great. My grandfather is not a guy who does something like that just to be nice. That was a big notch on my confidence belt.

But the best piece of advice my grandfather gave me doesn’t relate to music. I was about 14 and we were at the Montreux Jazz Festival in Switzerland. There was this pretty, young girl there. She was close to my age and he sort of looked at me and said, “These boys don’t know what they’re doing. All it’s about is humor. If you make a girl laugh, that’s it. That’s all they want is to laugh.” He was like, “You’re funny. Just go be funny.” That trip affected me big time because we spent so much time together. It was all about staying up all night, going to see music and hanging out. Maybe not the norm for a traditional grandfather, but he’s Quincy Jones.

—