The film Machete was a joke from the start. It began as a trailer with no movie to go with it, made as part of Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez’s double-feature Grindhouse, a movie about bad movies. Then, when Rodriguez decided to make his farce into a real film, a comedy about border issues centered on a Mexican-American super killer, he chose as his star a guy who’d stumbled into movies accidentally.

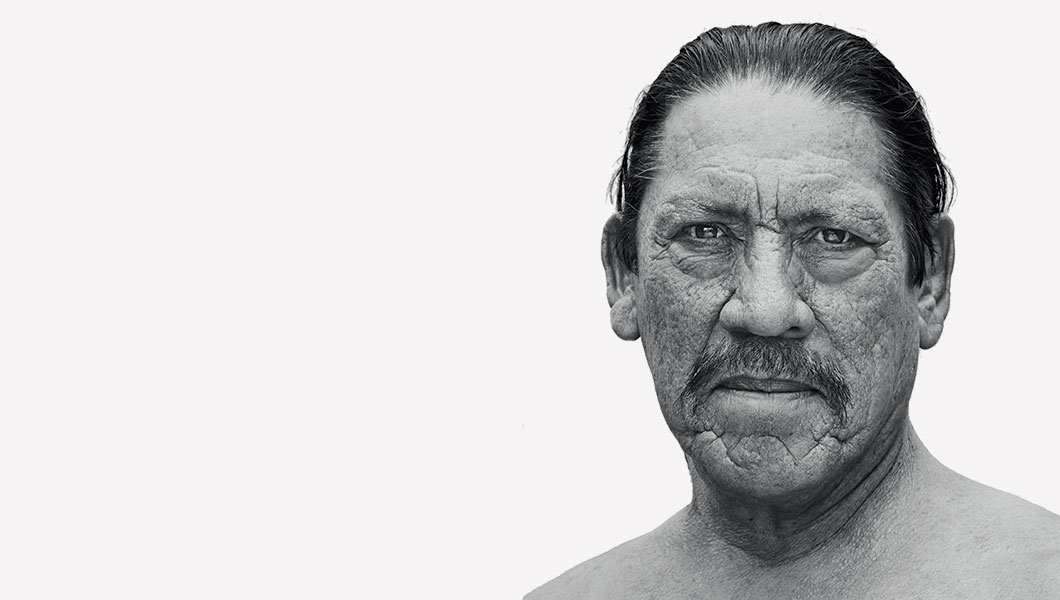

Danny Trejo, a born-and-raised Angeleno with long dark hair, a gravelly voice and a distinctive weathered face, would be “Machete.” And he would be quite good at it: He’d take low-riders on spins, use knives to fight off gun-toting villains and get the girl despite the odds. At 66, he would go from supporting actor to leading man.

“My mom was calling me Machete before she passed,” remembers Trejo. He’s sitting in his backyard in the San Fernando Valley, a few yards away from his prized avocado tree. He’s wearing boots and black pants, but he’s just taken off his shirt for a photo shoot—the photographer wanted to see the tattoo on his chest, of a woman wearing a sombrero. Nearby, there’s an oblong swimming pool with a machete tiled into the bottom of it. He laughs about that.

“I was in France,” he says. “Max, my assistant, he put that big machete down there.” It was meant to be funny. The oversized machete-shaped decorations on top of his garage are meant to be funny too. “I love it,” Trejo says of the machete joke. Three of his five dogs gallivant around the yard, and the smallest jumps up to rest his paws on Trejo’s lap. “That’s John Wesley Harding,” he says of the dog. “The meanest cowboy in all the world.”

Trejo, who refers to himself as a drug counselor rather than an actor, was born in 1944 and grew up on Temple and Figueroa, near downtown L.A. He had a rough youth. He developed a drug habit early and participated in a string of armed robberies, going in and out of prison several times before landing in San Quentin on drug charges. While there, he fell in with a group of men in on murder charges. For a price, they would protect newcomers from the inevitable dangers of prison life. “Prison is the only place in the world where there’s only two types of people: There’s predator and there’s prey,” says Trejo. He learned to be a predator with a business plan.

In 1968, he and two friends were involved in a prison riot. A sergeant was hurt, as was a civilian. While in solitary confinement, sure he would receive a death sentence, Trejo prayed. “God, if you let me die with dignity,” he remembers saying, “I’ll say your name every day and do whatever I can for my fellow man.” But charges were never pressed. “One thousand guys on the yard and they couldn’t get a single witness,” Trejo chuckles. “I thought it would be a couple of years before I’d be dead. It’s been 46 years now.”

He was released in 1969 and started working as a drug and alcohol counselor a few years later. In the mid-1980s, he went to visit the set of Runaway Train to check up on a kid he was counseling who was working as a PA on that set. While there, he ran into an old prison friend turned screenwriter, Eddie Bunker, and before he knew it, he had a small role in the film.

“And I just kept getting job after job. I found that if you’re pleasant, people tend to gravitate toward you,” he explains. “The first five years of my career, I was just ‘Inmate Number 1,’ ‘Bad Guy 5,’ ‘Tattooed Guy.’ I didn’t know what typecasting even was.”

He remembers being on a particular set and having a director pull him aside. “ ‘Danny,’ the director said, ‘I want you to hold this shotgun and kick in this door. It’s a robbery. You’re going to rob a poker game.’ ” Trejo kicked in the door, taking out a stuntwoman and a “big hillbilly” before the director yelled, “Cut.”

“My god, Danny, where did you study?” the director asked.

“Vons, Safeway,” Trejo answered. It had all come back to him immediately, the adrenaline rush and the performance of being the robber in real life.

By the mid-1990s, Trejo began to receive speaking parts. He appeared as Navajas in Desperado and a thug called Razor Charlie in From Dusk Till Dawn. Still, even after his movie career started taking off, he says he had no aspirations as an actor.

“I still work for Western Pacific Med Corp. That’s my real job. I still work with addicts and alcoholics,” he says. “Let me tell you what that did for me,” he continues, referring to his acting breakthroughs. “My passion is talking to young kids in trouble. Well, the trouble with talking with kids is that first you have to get their attention, which is impossible because they have none. And then you have to keep their attention, which is impossible because of number one: They have none.” Now, he goes to schools and kids listen. “Not Danny Trejo, that’s not who they’re listening to, but the guy from Spy Kids, the guy from Desperado, the guy from any movie they’ve seen.”

All the assistants who live in his house, who have been coming out to feed the dogs and who take care of business when Trejo’s traveling, are former addicts he’s counseled. Today, his 27-year-old son Gilbert is in town and the two are driving down into Hollywood to take a meeting at the American Film Institute about a script Gilbert wrote, a strange spin on Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up and Brian De Palma’s Blow Out. Trejo’s most recent project was a PSA for the Friends of Animals, for which he wore a full-body dog suit and played “T-Bone.” He’ll sign autographs in Canada later this week.

“I’m blessed,” says Trejo, recalling something Eddie Bunker told him: “The whole world can think you’re a movie star, but you can’t.”

—