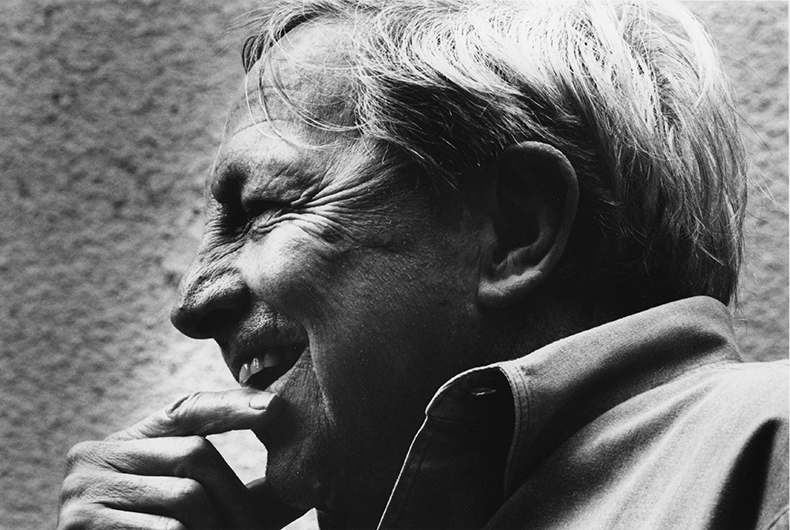

ROBERT T. KNIGHT MIGHT JUST BE CHANGING THE FUTURE OF HOW WE THINK.

That’s not hyperbole—the neuroscientist, neurologist and UC Berkeley psych professor is working on projects that center on the brain’s frontal lobe, an area that’s at the core of understanding human beings and our diseases, neurological disorders and psychiatric issues. “We’ve been working with a group in Germany where we stimulated the reward area of the brain,” he says. “We studied five intractable alcoholics, and with that stimulation, they stop drinking. I’m also involved in a project where we’re trying to alter mood behavior by stimulation.” So someone whose depression hasn’t been treatable with medication could have their mood changed in a period of months—effectively altering their brain’s physiology. “I know it sounds crazy,” he acknowledges.

Knight is fascinated by how the brain functions and the way it misfires. For example, there’s been plenty of debate lately regarding head trauma in professional athletes. “I’ve been working on a new helmet,” he explains. “It diminishes the amount of force that gets to the skull and the brain when you’re hit.”

Another of his projects focuses on the brain’s response to marketing. Around seven years ago, he and two other scientists developed a way to measure people’s cerebral responses to advertising, working with an outfit called NeuroFocus. Nielsen (as in the ratings) was, of course, interested in the technology and bought the company. His ongoing partnership with Nielsen has allowed him to develop yet another monitoring system. “It’s a wireless EEG system, like a swimming cap, that records your brain’s electrical activity.” While a conventional EEG costs about $50,000, he’s optimistic about getting the cap’s cost down to $200. “Roughly 75 percent of the world doesn’t have access to an EEG,” he says. “So if a kid falls down, you don’t know if it was a heart event or a brain event. If we could get this into sub-Saharan Africa and rural China, you could measure anyone’s brain waves, transmit that information to an iPhone and transmit it to a neurologist so they could take a look.”

Given his impressive set of skills, you might be surprised by Knight’s upbringing, which wasn’t packed with Montessori schools or Baby Einstein DVDs. Raised in rural New Jersey near a Superfund site, Knight grew up in a 480-square-foot house, where he shared a tiny room with his brother. “My dad was an eighth-grade dropout—his father died and he had to work,” he explains. “His educational plan for us didn’t include tutors. It was basically, ‘Keep going to school till you can’t stand it anymore.’ As soon as we finished eating, my mom would say, ‘Get out of the house and don’t come back until the next meal. And wear clean underwear in case you break a leg.’ ” At night, he and his sibling would “blow things up and do all sorts of crazy stuff in our room.” That brother? He’s now a botanist who has discovered several new species. Knight says that at a family party years ago, someone asked his mother why her boys had turned out so well. She cracked, “I think there was something wrong with the water.”

There were more happy accidents along the way. “My plan was to become an architect, and the first day of college, they said you had to take mechanical drawing, and I said, ‘Forget it. What major doesn’t have that?’ They said physics,” he recalls. “So I became a physics major. I was basically functionally illiterate. Really. They let me substitute COBOL [an early computer-programming language] for my language requirement.” Then, one professor changed the course of his career. “I saw all these guys and gals who’d done Ph.D.s and postdocs in physics who weren’t finding jobs. So I asked my professor what to do. And she said, ‘You’re a smart guy—why don’t you go to med school?’ ” In his junior year, he applied to med school but realized that biology, which he’d never taken, would be on the test. “I got a biology book, read it, took the admission test and got in. You can’t make this crap up,” he laughs. “It’s serendipity.”

Since becoming a full-fledged scientist, Knight’s taken a special interest in epilepsy, which is sometimes difficult to medicate. “There’s about 3 to 3.5 million people in the United States with epilepsy,” Knight explains. “And of those, about 15 percent aren’t controlled with seizure medications.” To treat them, Knight and his lab team place electrodes deep in their patients’ brains. They’re taken off their meds and monitored in the hospital. “Once we’ve got three seizures that all come from some specific point,” he explains, “they go to surgery.” The onset spot is then removed from the patients’ brains. “It’s really a remarkable procedure.”

His current research is so complex and fantastical, it almost seems like sci-fi. But Knight is uniquely well equipped to explain his work in terms even a kid could understand. “I started a journal two years ago called Frontiers for Young Minds. We ask scientists to submit a paper targeted at 9-to-15-year-olds. Then kids review the paper, and the scientists have to make any changes they want. It’s really designed to empower kids, but I think it’s going to be a resource for anyone to get information in an understandable manner.”

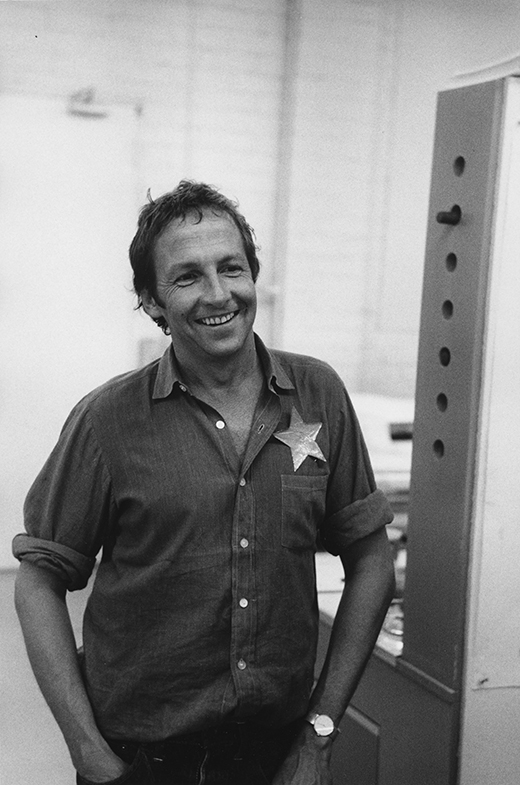

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke has awarded Knight (twice) for his work, and in 2013, he was given the Distinguished Career Contributions Award by the Cognitive Neuroscience Society. But he clearly doesn’t take himself too seriously. I ask about an odd-looking profile photo he’d posted online, on a medical journal’s website. “That’s my grandson eating chocolate out of the garbage can,” he laughs. “It’s funny you should bring that up. A week ago, the editors of the journal asked if I could replace it with another profile picture, so I sent them a shot of me wearing an Elmo shirt. So we’ll see how that goes. I’m not rolling easy—I’m from Jersey, man.”

—