Five years old and HIV positive, Kami is one of the most influential figures in her native South Africa. She also happens to be a Muppet and a character on Takalani Sesame, the country’s co-production of Sesame Street, which reaches up to 70 percent of children in South Africa’s urban areas and 50 percent in its rural ones. In addition to destigmatizing HIV/AIDS, Kami also educates children on the basics of her disease, including how it’s transmitted and how to deal with grief and the loss of a loved one.

As an indigenous puppet, Kami joins a unique cast of characters around the globe, developed to tackle issues affecting children or particular communities. In the 46 years since Sesame Street first aired on PBS, the preschool television series has become the go-to address for children in more than 150 countries. Through 30 international co-productions, such as Iftah Ya Simsim in Kuwait, Sesamstrasse in Germany and India’s Galli Galli Sim Sim, Sesame Street’s longstanding credo of helping kids grow smarter, stronger and kinder continues to resonate around the world.

Whether it’s a domestic production or a co-production overseas, Sesame Workshop, the nonprofit behind Sesame Street, takes a very mindful and studied approach to developing content. “What people don’t realize is how well researched the show is,” says Carol-Lynn Parente, who grew up watching the show and started out lugging tapes as a post-production assistant, working her way up to her current position as senior vice president and executive producer of Sesame Street.

In addition to overseeing all Sesame Street content across all platforms from the company’s New York City headquarters, Parente is responsible for international co-productions and outreach production. “The process starts off with an entire educational content seminar, where we bring in academic advisors and early-childhood-development experts and they talk about what our curriculum focus is for the season, so we can really understand what we want to teach and in the right way for the age of our audience.” Content is tested before it goes on the air and after, and tweaked and adjusted accordingly. “It’s been the most heavily researched and tested show in history,” she adds.

Internationally, the process also involves partnering with ministries of education as well as broadcasters, producers and educators on the ground. “Across the board we look at what are the most pressing needs facing children around the world where we are most uniquely qualified to make a difference. We look at our skill set and their needs and figure out where they match,” says Sherrie Westin, executive vice president of global impact and philanthropy at Sesame Workshop. Westin stresses the importance of working with local partners on the ground to identify issues on an ongoing basis. Takalani Sesame, for example, was already on the air when the South African Ministry of Education approached Sesame Workshop about discussing issues surrounding HIV and AIDS. “The reason [these shows] translate so powerfully is we don’t try to parachute American cultural lessons,” says Parente. “In South Africa, there was a real need to connect on HIV/AIDS.” In season two, Kami joined the cast after lengthy discussions and research on everything from her outfits to her personality (“We want little girls to see themselves in her but also be aspirational,” says Westin). In breaking down the stigmas surrounding HIV/AIDS, Westin believes that Kami is bound to have saved lives.

That power is also evident in places like Egypt, where a charming peach-colored girl monster named Khokha on Alam Simsim is already changing attitudes about young girls’ roles and responsibilities. In just a few years since her debut, research has not only demonstrated a positive shift in how girls see themselves, but young boys also tested much higher on gender equity. “It’s essential for us to change cultural norms in a nonthreatening way,” says Westin. “To open minds and to change attitudes is really powerful, especially when you are starting with the youngest generation.”

Westin hopes to see that same shift in mentality in Afghanistan, where an indigenous puppet will make her debut on Baghch-e-Simsim in 2016 as part of an initiative to promote girls’ empowerment and education. Since the show’s premiere in 2011, focus groups and qualitative research have already showed fathers changing their minds about sending their daughters to school. “We are not only reaching girls that have no other means of quality preschool education; we are giving them the tools for education and for being aspirational role models,” says Westin.

But it’s not just international markets that have a need for these role models and attitude shifts; Sesame Workshop remains focused on its domestic audience, too, where past programs have dealt with issues ranging from incarceration to healthy eating habits. In 2006, “Talk, Listen, Connect” was introduced as a bilingual (Spanish and English) outreach initiative designed to help military families and young children cope with issues surrounding deployment and change. The immensely successful program—which saw Elmo’s dad being deployed—has continued to expand, growing to include “Military Families Near and Far,” a designated website for young children to connect with their loved ones, as well as PBS prime-time specials and “Sesame Rooms,” which provides toys and furniture to military spaces.

Most recently the workshop introduced Julia, an animated preschool character with autism. She’s leading the charge on Sesame Street’s newest initiative, “See Amazing in All Children,” designed to destigmatize and raise awareness about autism, a disorder that affects one in 68 American children. “It’s a difficult subject,” explains Parente. “Many people want to support this community and don’t know how. We were very thoughtful and took our time figuring out how we as a media company could have an impact.” The digital project, the result of three years of production and testing, includes a “Sesame and Autism” website/iPad app, video topics for affected kids and families, daily routine cards to help with basic skills like washing hands and brushing teeth and an interactive storybook that introduces Julia to some of the Sesame Street gang.

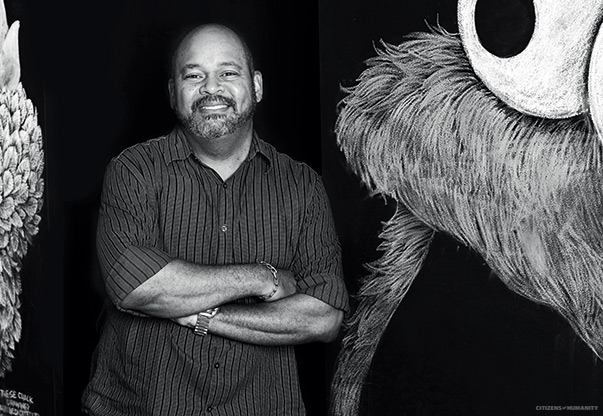

“Every character is designed toward a curriculum goal. Everyone here takes the time to understand what it is, the problem they want to address and what are the best approaches,” says Louis Henry Mitchell, creative director of character design for Sesame Workshop, who has been with the company for 23 years (he came on board full-time in 2000). In addition to his regular roles and responsibilities (which range from directing photo shoots to assisting in the creation of Sesame Street’s Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade balloons and floats), Mitchell was tasked with designing Julia—basing his sketches off a girl he befriended while volunteering at a school for autism. “I gave three different designs, and a committee of people working together decided who would be the best representation. The one I wanted is the one they chose,” he says, proud that his gut instinct served him well.

“Wherever the characters appear, I have to make sure they look right,” says Mitchell, who co-created Kami’s look and helps oversee and evolve character design according to the standards set forth by Muppets creator Jim Henson. Artists around the world looking to draw or sculpt the characters can refer to several in-house style guides. “The eye focus is probably the single most important piece. Whether it’s still life or sculpture or drawings, the eyes are where the life is.”

As important as the finely tuned international cast of characters is the platform on which their heartfelt and engaging messages are delivered. “The evolving media environment has changed the way we produce content enormously,” says Parente, citing a large percentage of Sesame Street’s audience that now watches the show on mobile technology. As a result, the show has adapted its visual style (wide shots, for example, don’t translate well on mobile devices). The producers also create material specifically for YouTube, for example, as well as online gaming content with educational benefits. “I feel like some of the new platforms mirror what [Sesame Street co-founder] Joan Cooney stated in 1969, that she was using television as an experimental way to teach. An innovation lab is dealing with all the emerging technologies and figuring out how to use them.”

And in communities where technology is limited or access to television is restricted, the show has also found ways to reach young viewers: In countries like Afghanistan, Baghch-e-Simsim also airs on the radio, and in Bangladesh, a traveling rickshaw fitted with a television brings the show Sisimpur to children in urban slum communities.

Also of note is who is watching the content with the children, so if you think Sesame Street content is created only with preschoolers in mind, think again. “Back when the show started there was a lot more co-viewing that went on,” says Parente, referencing television as the primary medium during the show’s early days. “We know the educational impact is deeper when children are co-viewing.” So it’s no surprise that over the years, the show has seen a star-spangled list of celebrity guests, ranging from Stevie Wonder to Johnny Cash, Adam Sandler to Katy Perry. “These days there’s lots of viewing with tablets and devices that are individual, but it’s important for us to still find those moments—whether it’s with a celebrity or the comedy of a piece,” she adds.

Meanwhile, back in the U.S., Sesame Workshop inked a deal with HBO to begin broadcasting new seasons of the show in late 2015. The partnership brings a sustainable funding model to the nonprofit, and episodes will run first on the premium cable network before airing on PBS, Sesame Street’s original home, nine months later.

However preschoolers around the world get to their own version of Sesame Street, the destination is one and the same: a warm and engaging place where young children not only learn the basics about numeracy, literacy and social and emotional skills but can also develop a sense of empowerment and belonging in a culturally sensitive environment. “They think it’s fantasyland but it’s real,” says Mitchell with a smile. “I work here every day. I know it’s real.”

—