The week before a big sale, Brett Gorvy has a ritual. “I get up very early in the morning, before the day begins,” says the Chair of the Post-War and Contemporary Art Department at Christie’s, the auction house that has been in business since 1766. He heads straight to Christie’s New York City headquarters on Avenue of the Americas and goes to the salesroom as soon as he arrives. There, the art soon to be auctioned has been installed in an exhibition that probably won’t stay up for more than a week. “I spend time enjoying it, all the work.”

Gorvy, who has made Art Review’s annual Power 100 list for the past decade, has been the sole head of the department since 2011, a year before Post-War and Contemporary surpassed Impressionism as the auction house’s most lucrative category. Before that, he headed up the department collaboratively with chic, photogenic Amy Cappellazzo, known for saying quippy things like “so much for the weak dollar” after a significant sale. She moved on to development before leaving the auction house to pursue other projects in 2013. When Gorvy officially took the helm, Steven Murphy, Christie’s CEO, cited his “museum-quality presentation of the sale previews” as evidence of his aptitude for his job.

So Gorvy has organized, and thus seen, quite a few of these salesroom shows over the years, many featuring staggeringly valuable artwork by icons: Warhol’s silkscreen, “Statue of Liberty,” in 2012, or Lucian Freud’s “Benefits Supervisor Sleeping,” a gritty painting of a fleshy, nude woman on a couch that sold for $33.6 million in 2008, when Gorvy and Cappellazzo still worked as a team. Sometimes, though, it can be hard to feel excitement when you’ve been immersed in the logistics of transporting work, inspecting it, installing it and assembling catalogues. You could feasibly enter a salesroom that includes, say, Jackson Pollock’s “Number 19,” a painting that spent 10 years out of public view before selling at Christie’s in May 2013, and feel little to no awe. But Gorvy felt awe one morning last autumn when he arrived to spend time with the art set to sell on November 12, 2013.

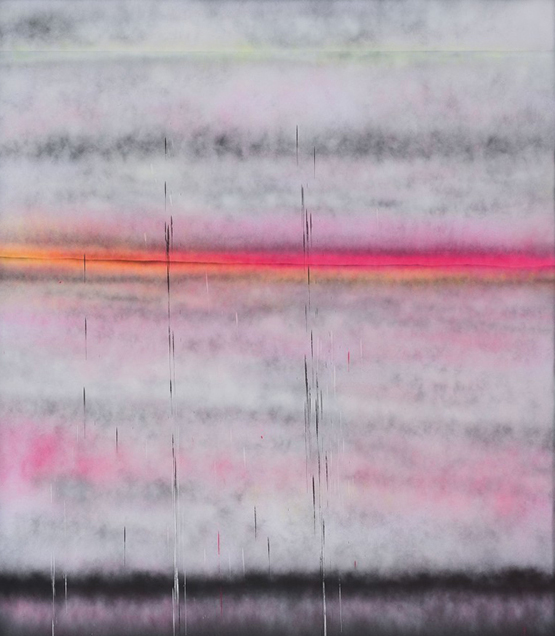

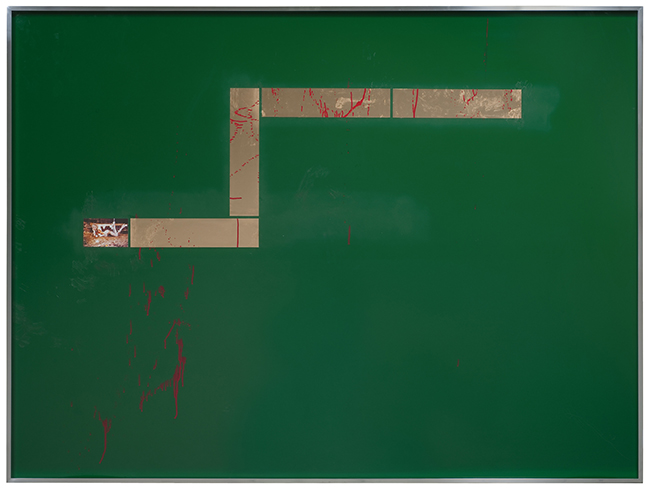

“I’d never seen a room wall-to-wall look as good,” he recalls. “It’s rare that it happens that way—by the time you get to the sale, it’s inevitable that you have these ups and downs. What defined it for me was that ultimately every movement was represented—the ’80s, the ’90s.” He saw Christopher Wool’s “Apocalypse Now,” a black-on-white text piece that announced in all caps, “SELL EVERYTHING, SELL THE HOUSE, SELL THE CAR, SELL THE KIDS.” He saw a Jackson Pollock painting and the perfectly polished, shining orange, towering balloon dog by Jeff Koons. Then there was Francis Bacon’s “Three Studies of Lucian Freud,” a loose trio of portraits of Freud, also a painter and grandson of the original psychoanalyst. Each six and half feet tall, the three paintings have a yellow-orange and pea-green background, and a strange, fragmented frame near the center. Inside of that frame, on a wooden chair, sits a man—Freud—with one leg crossed over the other. His face, all bulges of gray and pink, is distorted like faces always are in Bacon’s work. “MoMA doesn’t have a Bacon of this caliber,” says Gorvy. He remembers thinking, “I’ve got a sale the people should see. Auction history will be made.”

Gorvy had already intended to send out a standard email later that day, pitching the show and sale to colleagues. “I decided I’m just going to dictate,” he recalls, and tried to convey his enthusiasm spontaneously while an assistant transcribed. The resulting memo would be picked apart on New York Magazine’s Vulture blog and posted in full on the art news source GalleristNY. (“Folks, there is effusiveness, and then there is Brett Gorvy,” read the Gallerist intro.) In subsequent weeks, its tone would also be mimicked by other auction houses.

“I am rendered rather speechless by the works,” the memo began. It continued: “In my heart, I believe the results this week will be extraordinary.” They were. The Francis Bacon triptych sold for $142.4 million, making it the most expensive painting ever sold at auction, outstripping Edvard Munch’s “The Scream,” sold by Sotheby’s for $120 million in 2012. “A historic moment,” the auctioneer actually said while bidding was still under way the night of the auction. People cheered when it sold. Jeff Koons’ “Balloon Dog” also set the record for an artwork by a living artist—noteworthy, but also no longer unexpected, seeing as Christie’s has set records in Post-War and Contemporary sales each year since 2010.

“We have barely had five days to enjoy this kind of caliber and beauty,” Gorvy’s memo also said. “Each season I wonder if we can do this again.” And then they do.

Gorvy speaks on the record about sales results, market trends and specific artworks frequently. It’s rarer for him to talk about his personal tastes or routine, though he and his wife, art dealer Amy Gold, did give Architectural Digest a tour of their apartment late in 2013, showing off an art collection that includes rare photographs documenting work by visceral feminist artist Ana Mendieta and a drawing by 1960s jack-of-all-trades Bruce Conner. Gorvy’s relative quietness regarding anything other than work may have to do with a natural desire for privacy but probably more with sheer busyness. He is in airports constantly, out of the country as often as in.

Born in South Africa to British parents, he spent the first part of his childhood in Johannesburg, then moved to London in the mid-1970s, when his father, financier Manfred Gorvy, relocated for work. Manfred would soon found the highly successful real estate and development company Hanover Acceptances Limited, and he and his wife, Lydia, collected art, so Gorvy and his three siblings grew up around it.

As a student, Gorvy studied art history and began a career as an art journalist in London in the late 1980s. He was still happy reporting on the art world when a friend of his, who worked at Christie’s longtime competitor, Sotheby’s, offered him a job. He turned it down. But in 1994, that same friend had accepted a new position at Christie’s. “He offered me the job again,” says Gorvy, who accepted this time, ready for a change. “I’ve been rather lucky,” he adds.

Before he began at Christie’s, even though he knew art well, actual, iconic paintings and sculptures seemed distant to him, certainly not like things you could get close enough to touch. This quickly changed. He remembers an early experience he had at the auction house. “I went into a warehouse and, on the table, there was a small copper Modigliani out of its frame,” he says.

He picked up the piece by the Italian painter, a prolific, stylish Bohemian who once criticized Picasso for being “uncouth.” “I felt the weight of the copper in my hand. You’re so close to the art—you’re seeing it naked.”

When Gorvy first started at Christie’s in 1994, the art market, like many markets, had been struggling. Art sales had boomed in the 1980s. Interest in young talent had grown as new money proliferated on Wall Street and the Japanese yen gained strength. Investors started to see art as a speculative asset, something you could buy for relatively little and then ideally resell for much more. Young graffiti artist Jean-Michel Basquiat became an overnight sensation, posing for the Newsweek feature “New Art, New Money: The Marketing of an American Artist” in 1985, at just 25 years old. Basquiat would tragically be dead of an overdose before prices plummeted in 1990, as the early ’90s economic recession began three years after the jarring 1987 stock market crash. Work by artists like Eric Fischl and Julian Schnabel, newly and excessively popular in the 1980s, and even work by Warhol would fail to find buyers. Gradually, though, over the next decade the market would build itself up to record sales levels, becoming more global and withstanding the dot-com crash. “I grew up basically as the market changed,” Gorvy says.

In 2003, the year he and Cappellazzo first made it onto the Power 100 list, they sold a Basquiat painting for more than $600,000, nearly $150,000 above the estimate but far less than what a painting like that would go for today—Christie’s sold Basquiat’s “Dustheads” for $48.8 million in the summer of 2013. After 2008, during the recession, the market dropped around 30 percent, but then Cappellazzo and Gorvy had auction sales up by over 100 percent by the autumn of 2010. Dubai and Hong Kong were growing markets. Now, it’s commonplace to see headlines like the one Art in America published in 2012: “Biggest Contemporary Art Auction at Christie’s New York, Again.” That time, the sale featured Basquiat, abstract expressionist Franz Kline and everpresent contemporary powerhouse Jeff Koons.

One explanation for this seemingly continuous growth is the new international vastness of the market. “You feel the Russians, you feel the Middle East,” says Gorvy, who values “being able to reach out and have that global connection.” But he dismisses the idea that breathtakingly big sales at Christie’s represent a mismatch between the money and the actual cultural value of the art. Collectors aren’t buying with their ears, based on what they’ve heard is hot, at least not the collectors who matter. “Every market has its great period,” he says. “In reality it’s not about the record making. It’s more about a passionate pursuit.”

Before a sale, when collectors can’t decide whether they want to buy, he tells them to imagine themselves waking up the next morning and not having that work of art. Would they kick themselves? “My wife and I collect,” he explains. “I know what it feels like. Most people want to own art because they want to live with it.” And these are smart people, Gorvy has said when interviewed elsewhere; they made their money doing something they’re good at and know what they like.

Throughout the years, Gorvy has held conversations in salesrooms with art historians, like the 2008 interview he conducted with Dr. David Anfam about abstract expressionism, or commissioned respected writers for catalogue essays, like novelist Jonathan Lethem, who recently wrote about Warhol. But the intellectual part is never the most important. “My job really is to make sure every work looks its best. It’s all an instinctive thing that hits you in the gut,” he says of collecting. It’s a revelation, to encounter new works, even by artists who have already made it into history. “You think you know an artist and then you see a new painting. You come face to face with an amazing object.”

“It doesn’t feel like work. You get on the plane—meet with someone who lives with art.” He’s in an airport as he says this, about to fly to Europe to meet with a collector who’s been living with paintings Christie’s briefly had under its roof. This part of the job never fails to excite him. “You’re humbled, frankly, by the art.”

—