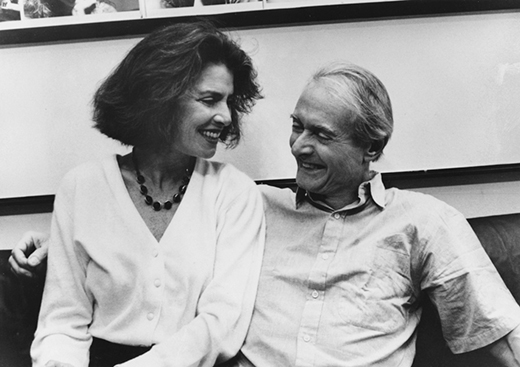

The call came one evening in November 1982. It was my friend and colleague Larry Gagosian telling me that Jean-Michel Basquiat was in Venice, painting for a new show and, more to the point, wanting to know if I would be interested in working with the artist to produce a special new work in silkscreen. At that time I owned a print and multiple publishing business in Venice called New City Editions.

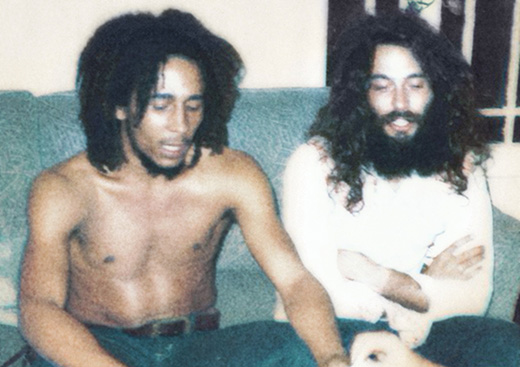

I met with Jean-Michel for the first time that same evening and thus began an incomparable experience—one I was unlikely to repeat. I was seeing a rare talent at work, apart from the New York art world from which he usually drew his inspiration. I was taken aback by the unique vision and conviction of this young man of just 21.

Jean-Michel came to Los Angeles with the desire to produce a truly ambitious silkscreen print. Starting with a group of 16 original drawings, he asked me to first reverse their content through photography (everything depicted in black would become white and the white background would become black) and then fuse together the entire suite of now reversed images into a single image which would be silkscreened onto a very large 8 x 5 foot canvas. This work, which Basquiat titled “Tuxedo,” was the first of six silkscreen prints which I produced with the artist in 1982-83. With the exception of one other silkscreen produced in New York earlier in 1982, these are the only limited-edition prints he produced in his short lifetime.

Continuing Basquiat’s interest in the silkscreen process, my small print studio facilitated production of approximately 30 original paintings on canvas which the artist executed in Venice in 1984. In these breathtaking works, Basquiat seamlessly integrated painted, drawn and silkscreened images into some of his more complex, multifaceted paintings.

Tamra Davis filmed Jean-Michel working at New City Editions in Venice in 1983-84, and this footage became a central part of her now acclaimed documentary, The Radiant Child.

In Venice, Jean-Michel worked from the ground-floor gallery and studio space Larry had built below his home. There, he quickly commenced what was to be an extraordinary series of paintings. They were for a March ’83 show, his second at the Larry Gagosian Gallery in West Hollywood.

Jean-Michel usually worked from late afternoon until the following morning, and I would regularly show up at the studio after dinner, confining myself to a bed set up in a corner of the room. I was mesmerized by his self-contained focus, his intensity and fluidity. He seemed to make time disappear, and evenings would quickly pass into the next day’s dawn. Overnight, paintings would undergo a transformation. New, seemingly more complex imagery would appear, and other imagery and surfaces that had seemed so perfect would be painted over and eliminated.

As an example of Basquiat’s working practice, one late-night experience still remains fixed in my mind. Arriving at the studio one evening, I observed Jean-Michel standing before approximately eight newly gesso’d white canvases. I had already retreated to the bed in the corner when Jean-Michel turned to me and declared that “tonight I’m going to paint the history of contemporary painting in California.” He then proceeded to attack each of these blank canvases with passages of paint, calling forth the styles of many of the leading abstract California painters, including Richard Diebenkorn, Sam Francis, Chuck Arnoldi, Ed Moses and others. It was uncanny how this young New York artist could quickly and effortlessly capture the spirit of these considerably different pictorial sensibilities. As I was watching each painting evolve, I must have drifted off to sleep. I awoke several hours later at dawn. Jean-Michel was no longer in the studio. Virtually all of the references to California abstraction in the paintings he had been working on were no longer visible. Rather, each picture had been painted over, leaving only the smallest passage of paint referring to the California painters.

When he returned to the studio the next night, he was now ready to turn each painting into a fully realized “Basquiat.”

The more I came to know him, the more I understood why Jean-Michel was drawn to work in Los Angeles. Here was a truly gifted young man who was quickly having to adapt to the increasingly complex demands of newfound success. Remarkably, only about 18 months after his work had appeared in two important New York group exhibitions—“The Times Square Show” in 1980 and “New York/New Wave” at P.S. 1 in Long Island City in 1981—he had become a victim of his triumphs. Although he certainly expected and sought out the public’s attention, he was finding it increasingly difficult to deliver to the ever-demanding, even usurious, art world.

Jean-Michel lived and worked at a furious pace. No one I knew could keep up with him. Although this served his incredible capacity to process the world around him, it did not serve his stability or physical well-being. In the removed environment of Venice, he seemed to find a security and solitude. Away from New York, this emergent talent was able to get on with his mission with significantly less distraction.

Los Angeles and environs also offered new source material and stimuli. While I was working with Jean-Michel on his silkscreen print editions, one day he experimented on an image containing references specific to his Venice experience. In this work, which was never released, the artist showed his fascination with Muscle Beach—things which he would not have encountered anywhere else. In this work Basquiat included the texts “How to Perform Strongman Tricks Without Strength,” “Barbells,” and “Two Hundred and Fifty Pounds.”

Several of the works in his second show at the Larry Gagosian Gallery referenced famous boxers, musicians and Hollywood films and the roles played in them by blacks. One painting, “Hollywood Africans,” produced in Venice, is most telling. It depicts the artist and two of his New York associates, Toxic and Rammellzee, essentially placing their black footprints into the history of Hollywood at Grauman’s Chinese Theater.

That Hollywood was a focus for Jean-Michel was driven home to me when I was asked to accompany him and Madonna to lunch at the commissary at 20th Century Fox studios. At the time, neither of these two future stars had received enough recognition to evoke any response from the sea of Hollywood talent. This lack of attention only made both even more determined that one day the focus would be on them. For me, it was a revelation: I was witnessing the determination and conviction of two clearly destined talents.

After his ’83 opening at the Larry Gagosian Gallery, Jean-Michel departed L.A. for a time. When he returned a few months later he wanted more privacy; and so I found him his own studio at the corner of Market Street and Speedway, a block from the Venice boardwalk. He worked there for about a year, through the first half of ’84, producing many important paintings.

Out the back door of the studio was a small patio, separated from the alley by a wooden slat fence. Early on I noted that parts of the fence were deteriorating and that the patio was not secure from the transients ever present around the boardwalk. After his usual routine of working all night, Jean-Michel stepped out onto his patio very early one morning, only to be startled by someone sleeping there beneath a blanket. He recounted the incident, and it was decided that, for safety’s sake, the fence should be removed. But rather than let the planks be thrown away, Jean-Michel wanted them brought inside. Within a day or two, many of the wood slats had been reassembled horizontally and attached to long vertical shafts of wood—a new form of picture support born directly from the Venice studio experience. The first wood-slat picture support was painted bright gold and became the background for the now acclaimed painting “Gold Griot,” depicting a looming and regally positioned head and torso. The discovery of a new means of presenting a painting had enabled the artist to push his work in yet another new and exciting direction. The Venice years were not only a prolific but pivotal period in Basquiat’s career.

—