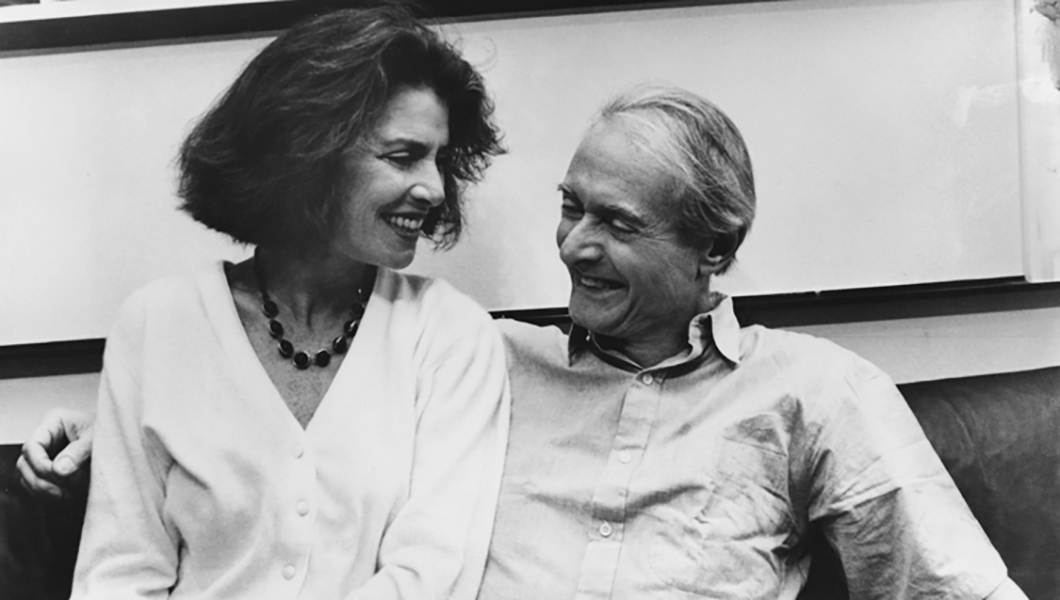

THEY SAY EVERY GREAT MAN HAS A GREAT WOMAN BEHIND HIM. DOROTHY LICHTENSTEIN PERSONIFIES THIS STATEMENT AND AT THE SAME TIME EXPLAINS WHY HER HUSBAND ROY WAS MUCH MORE THAN A MASTER OF CONTEMPORARY ART.

One of my earliest memories of art is the work of Roy Lichtenstein. As a child, I can recall staring up at the work and liking it for no apparent reason, other than just the pure enjoyment. Maybe it was the colors, maybe it was the patterns, I am not sure. But one thing was sure: I was completely unaware of the impact it would have on me for the rest of my life. Art has the ability to impact you in inexplicable ways. It influences thought, stimulates senses and affects emotion. It was Roy Lichtenstein who I have to thank for the beginning of an exploration that has brought me so much. As your tastes evolve and opinions form, it’s easy to over think art. But there is one truth that doesn’t get lost—the pure enjoyment of standing in front of something that truly puts you in a state of awe. When the opportunity presented itself to sit down with Dorothy Lichtenstein, Roy’s widow and president of the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation, well, needless to say, I was excited. Often, I think that you can learn more about a person by the company they keep, and spending time with Dorothy exceeded my highest expectations. She is truly a special woman. It left me wishing even more to have experienced the pleasure of meeting Roy.

JF: I guess we should start at the beginning. How did you meet your husband?

DL: I was working at an art gallery in 1964. We did an exhibition called “The Great American Supermarket” because some of the artists were doing things that dealt with food. Even Jasper Johns had done beer cans, and Andy’s soup cans were in the exhibition. We thought instead of a poster, it would be great if we could get Andy Warhol to put an image on a shopping bag. Those times were very simple. We asked them. They agreed. I actually met Roy when he came in to sign the shopping bags. Andy had put a soup can on it, and Roy drew a turkey on it. So that was, you know, our announcement for the exhibition.

JF: What were some of the qualities that you initially liked about him?

DL: Well, his sense of humor. Let’s see. I met him, but he actually had a girlfriend at the time, and I had a broken leg. We went out and we had lunch. I just thought it was endearing. He was having a show in Europe in Paris, and he told me, he promised, he was breaking up with his girlfriend, but he had promised to take her to Paris, and so he had to keep that promise. He called me when he came back.

JF: And in 1968, you were married, right?

DL: Yes. But we met in ’64, 1964.

JF: And at that time, was there any way to possibly imagine what the art world would become?

DL: Well, absolutely not to what it’s become. I think people, artists, were happy if they didn’t have to have a day job. I mean, artists either taught or drove taxis or did something so they could earn a living. Even though money was certainly different then, but I think they were just really thrilled to stay afloat. I remember living in a kind of loft space that was something like $120 a month, and a friend of ours who used to call himself “slumlord to the artists.” He used to fix up lofts. He would actually put hot and cold water in and make spaces livable. He sold a huge bank building on a corner to this photographer. It’s still there, on the corner of Spring and Bowery. It’s a huge corner building, and it was built as the Germania-America Bank around the turn of the last century. When World War I broke out, nobody would put their money in the German bank so it was empty and it was used for records. Actually, the photographer still owns it. Anyway, we took a floor in it, and I remember the rent was like $300. We were thinking, well that was probably 1966, 300 dollars, how are we going to pay him 300 dollars? It was just sort of a different time in New York and all over the world. I think nobody ever thought they would actually become rich making art. I was at the Koons show last night, which is pretty great actually. I was thinking about how we used to joke. The first time Roy got a check that was from the gallery that was a little more than 10,000 dollars; I remember he said, “Look, we are thousand-aires.” He grew up in New York City, in a kind of upper-middle-class home, but as an art professor, there was very little; the salary was low, so we thought it was amazing [to be paid more than $10,000]. People still thought of artists in terms of the starving artist. Now that idea seems like something that was 100 years ago, like Van Gogh to Andy Warhol. You know, 1860 to 1960.

JF: And now it’s just like completely gone, it seems like.

DL: It is. Well, the truth is, of all the artists working or on the planet, there is probably a tiny percentage that actually make it, you know, actually become—

JF: Successful?

DL: Well successful, and make an impact. The ones that I have known, they are just sort of generous by nature I think. Bob Rauschenberg was a good friend, and he just thought art could save the world, bring peace, and he acted on it.

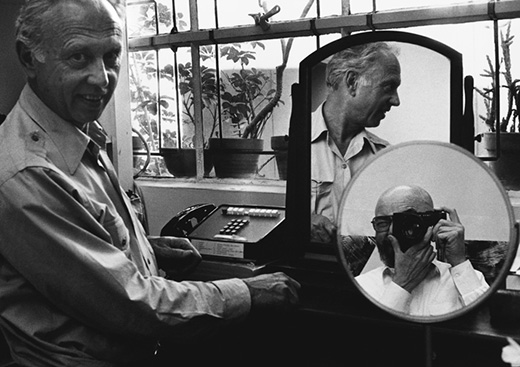

JF: I am curious. When did you both start to realize that he was going to be considered one of the premier artists of his generation?

DL: You know, he had a show in Paris in 1968. I somehow convinced him. Those were days when you stayed away on a trip for something like 24 days or more. You could get a discount on your airfare. It’s a crazy idea, but I convinced him that we would save money by going to Morocco. We were down to the southern tip of Morocco. Suddenly, in the middle of this sandy town in the last village, someone started calling, “Hey Lichtenstein!” And Roy turned to me, and he said, “I must really be famous.” It was a poet we knew, Ted Jones. He had been living in Holland with his girlfriend, and by coincidence, he was in the same small village in Morocco. I don’t think he ever, I think he thought that fame was fickle. He used to joke and say, “I’ll be sitting in my wheelchair with a crooked hat that someone just put on my head, and the nurse will be shaking me and saying, ‘Mister Lichtenstein, it’s time for your medication, get up.’” This all would have been a dream. I think he took it more or less with a grain of salt.

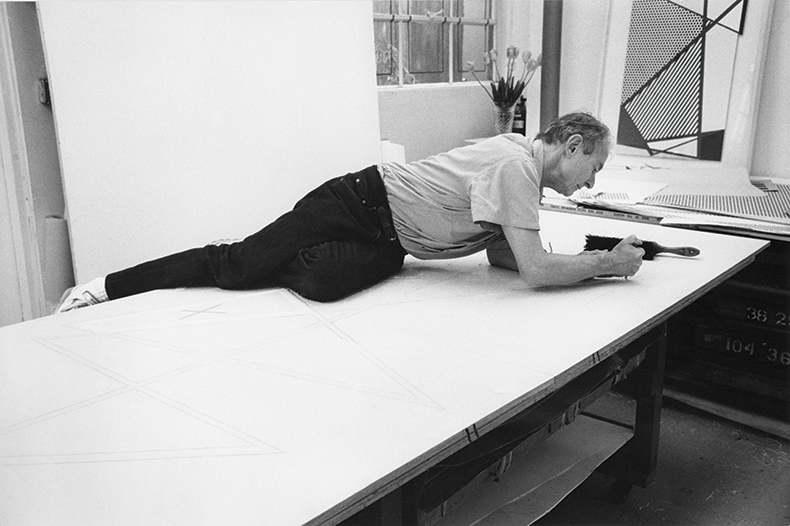

JF: What was your favorite part of watching his creative process?

DL: He really took time. He loved being in the studio. He was pretty regular to get down there. He really always managed to be down in the studio by 10 because people would come to work. Although, at that time, he only had one assistant and a kind of secretary, he was really willing to put in the time. If he was stuck, he might just come down and clean brushes, rinse them off. He put in the time, and whenever he was having an exhibition, there was never a question of meeting a deadline. He was already working on the next group of paintings or a sculpture or prints. I think even if it was graphic work, which people considered less important than paintings, I think he brought just the same creative juice to that.

JF: It’s interesting because the reputation I heard about him is almost contrary to what you come to expect from a lot of artists.

DL: I know. He was a secular humanist; that was kind of a nice thing. He treated everybody really as an equal. But talking about his work habits, he was very musical; when he was a teenager, I guess he heard Charlie Parker play. He had a friend—even though they were underage, they used to go down to the jazz clubs on 52nd Street. He had this ability—I was taking flute classes, and he had this ability, he could just pick up this flute, and if the radio was on, or television, he could just hear something and play it. His favorite instrument to listen to was the saxophone. I bought him a sax for his 70th birthday. He was really good at it, but he actually became a beginner. When I saw that, I realized what a gift it was. He practiced every day [just like a beginner] before we were going out. He’d actually leave the studio an hour early. Our friend, who helped me buy the saxophone, and I gave him six months of lessons with it. And at one point, our friend said, “Look, I know you know you have a sort of talent, but if you are not going to really study, then there is no point taking lessons.” Then Roy really did. He brought this beginner’s mind to doing it, and I realized that was really the gift he had with his painting. He had this enormous power of concentration and would direct it when there was something he wanted.

JF: I suppose that’s how he could really work on such different bodies of work?

DL: Well, he usually worked in groups. After he did something that might be very elaborate or involved, he might do something minimal or that could almost pass as abstract. He definitely brought that approach to his work, and he would make little sketches in notebooks or plan a group of paintings, and then if he was going to use it, he’d decide what size they should be and then project them. He had this opaque projector. Then he would loosely draw and then kind of redraw it on the canvas. His early work looks very artistic comparatively. To make the dots, he used a brush that he would dip in paint so they were very spotty. Later, he was able to get a piece of metal that was perforated which he’d have to clamp onto the canvas. He used oil and magna, which is unusual. Artists usually use oil or magna, but the dots had to be done in oil. Then eventually he could order perforated paper that you could just glue onto the canvas and rip off and wash. Actually, the methods of how he could paint changed as he learned different systems.

JF: What was it like among other artists—was it competitive? What was it like with dealers? What was the community like?

DL: He was lucky with Leo Castelli, really, the entire time of his career. They never even had any kind of contract. It was kind of a celebratory time, because people were paying attention. There’d be several openings on a Saturday. At one point, the openings were Tuesday nights. If it was a friend who was having a show, we’d usually wind up going to Chinatown afterward, because everyone could afford it at that time—a lot of food for a little bit of money. They really didn’t discuss, they didn’t get into, you know, the philosophy of art really, the way the abstract expressionists did, which would lead to big fights, of course. There was a lot of camaraderie.

JF: I read somewhere that you really loved Matisse. What artists did you both like to collect?

DL: Well, we did [like Matisse]. When we collected, we collected mostly drawings, Rauschenberg, Jim Rosenquist. I think Roy really felt that you could see, even if it was rough or exact, you could really see the hand of the artist; that drawing was the essence, the base of, you know, all art.

JF: What did the two of you like to do together?

DL: When we weren’t going out, we used just to like to hang out; maybe watch something on television, or just go out to eat. We stayed pretty much together. When we moved to Southampton in 1970, we were alone so much of the time. It wasn’t even called the Hamptons. It was pretty quiet. We had some friends—Larry Rivers, and we actually met De Kooning.

JF: Any memorable trips? Where did you like to travel?

DL: Roy only liked to travel for work, if he had an exhibition, or if he was working. He loved going out to California, to Gemini. Do you know that place? That was his idea of having to leave New York in cold winter, and we always used to stay at the Chateau [Marmont]. It was great, because we had an apartment, and we had friends there. That was his idea of a really great trip.

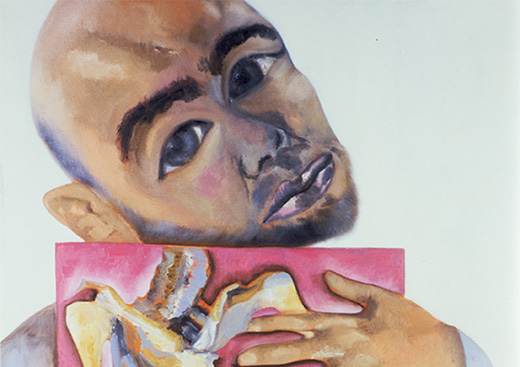

JF: Was there any specific body of work of his you liked most?

DL: Well, I really loved different ones at different times. And then, when Roy did these mirrors, I just loved them, because they looked like complete abstractions. You could read them as a mirror. One of the last groups he did, which were these landscapes in this Chinese style, I really loved. And then later on, he did a series of nudes, of two women, and it’s kind of ambiguous, but especially when I saw them at The Tate, because they have them high on the walls. I thought they were really different. At times, you could almost say that style was his subject matter. He did paintings that were made up of conceptualized brushstrokes and, well, actually the brushstroke itself. I think painting a conceptualized brushstroke is ironic—his work always had some irony in it. He wasn’t celebrating cartoons, but really more portraying archetypes of, say, the lovelorn girl, or sculptures of brushstrokes. I just think, how come nobody thought of it before. I thought that was an amazing idea.

JF: What’s your view on the art world today? Because of its popularity, do you think people are collecting art for love of the work or getting sidetracked, and missing out on the real enjoyment of collecting art?

DL: Well, I think, for whatever reason, maybe they enjoy having paid the highest price ever. Maybe it is more conspicuous in art, but it’s sort of this idea that money became the measure of everything, and that is so disheartening, because it reduces everything to what it costs. I do think that’s become a big part of the art world, but conspicuous consumption is all around us. It gets so, I don’t know, slick. Even myself. I used to like the fact that I had an old 1951 Ford Woody or this crazy old Jaguar that you couldn’t drive more than 15 miles without having it stalled. I guess I just have just seen it all. It’s like in the movie Get Shorty. In the end, when he comes out and there are all those black vans parked. I don’t know. I think that if you are an artist and you are working and that’s what you are given in life, that you go to art school. I am just comparing it to the fact that once upon a time no artist ever expected to really make money unless he was Picasso.

JF: It is funny, because at least for me, I am in my 30s, but I have romanticized about that generation of artists and now it does feel so slick. Sometimes it just feels like there is not enough substance.

DL: Yes, I know. I have that too, and sometimes I think I am just a dinosaur. The truth is that in the late ’60s, and even in the early ’70s, for minimalism artists like Don Judd and Karl Andre, it was really a struggle for an artist and the art galleries. They would close in the summer, but it did seem that certain things had more value. I mean, even a professor or a really good teacher was something that was valued.

JF: My last question [almost]. Who are today’s artists that you like?

DL: Let’s see. I really like Ellsworth Kelly, who is 91 now. I still really like the work that he does. But of the younger artists, I like David Salle’s work a lot, but I have to say, I don’t follow [it too closely]. I don’t really go around to galleries so much like I used to. Part of it is that I am not in New York so much, so it’s really hard for me to judge.

JF: What do you think Roy and his peers would think of it all?

DL: Well, I think Andy would have absolutely loved it. When I was in Paris last year, I opened my mini bar, and I took out a Perrier with an Andy Warhol on the Perrier bottle. Andy Warhol is, like, as famous as Elvis Presley.

JF: Maybe more so.

DL: Maybe more so. More famous than God. [ laughter]

—