SIDNEY FELSEN WAS AT THE EPICENTER OF THE ART WORLD IN THE 1960S. HIS PRINT SHOP AND STUDIO, GEMINI, WAS HOME TO THE MASTERS OF CONTEMPORARY ART: JOHNS, LICHTENSTEIN, RAUSCHENBERG, STELLA. BUT MORE IMPORTANT THAN THE ART CREATED INSIDE THE WALLS WERE THE FRIENDSHIPS, STORIES AND MEMORIES MADE THERE.

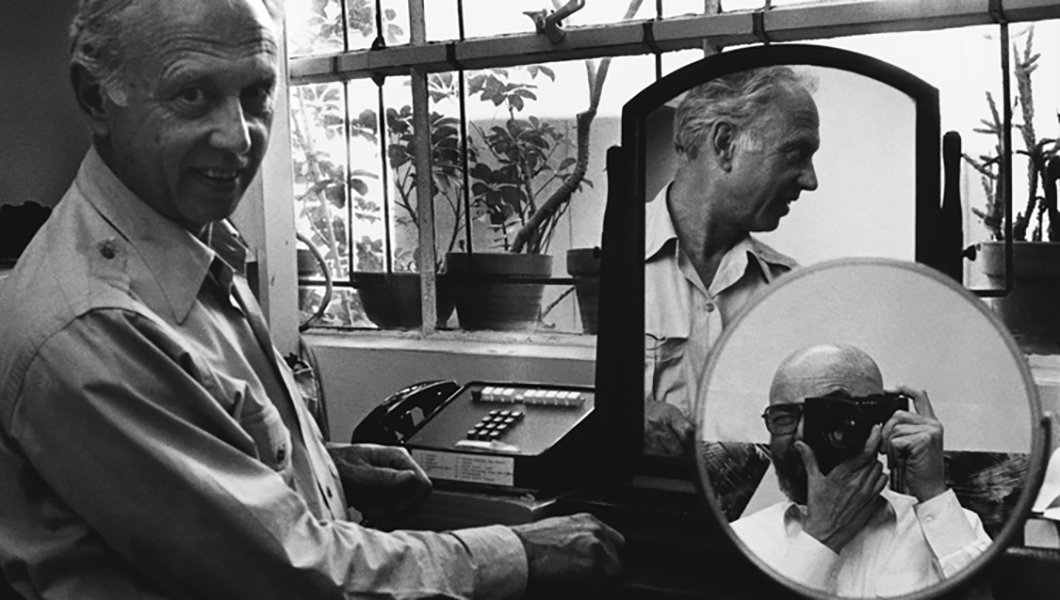

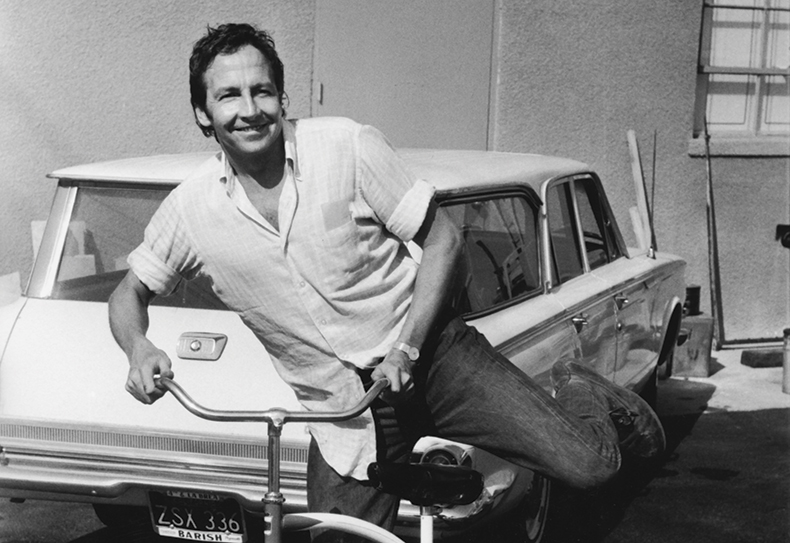

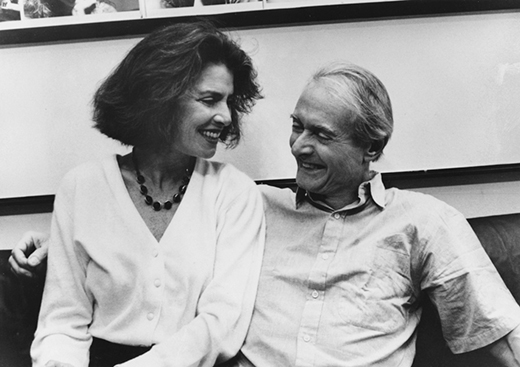

When best friends Sidney Felsen and Stanley Grinstein decided to try their hand in the art world there was no intention of reserving their place in art history. However, today there is no denying it. In 1966, together with master print maker Ken Tyler, they founded Gemini G.E.L., a print studio and artist workshop in Los Angeles. It wasn’t before long that the masters of American art history ( Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg, Richard Serra, Frank Stella, etc.) would make regular pilgrimages to California to create at Gemini. I sat down with Felsen, who turns 90 this year, to discuss everything from the creative process of Bob Rauschenberg to the basketball skills of Frank Stella and Bruce Nauman, and how two best friends turned a passion into an institution.

JF: Where did the name come from and what inspired the idea to open Gemini?

SF: The studio was started at the same time as the launching of the Gemini space capsule, and so that was an easy connection. How it started? In my own case, I grew up knowing I wanted to be an accountant. I majored in accounting, I graduated college, and I became a CPA and practiced accounting for many years. But somewhere along the way, I became interested in learning about art. I started reading about it, and then started going to art galleries, and then decided I wanted to paint. I first took painting lessons at the Frederick Kann School of Art here in Los Angeles. I studied painting there and then started going to Chouinard, which later became Cal Arts. I took just general courses in painting, drawing and sculpture and became interested in ceramics. I went to art school for 15 or 20 years, just for fun, weekends and evenings. Then I had a client who had an art gallery, and he was importing prints from Europe, and it looked interesting to me to have something like a workshop in Los Angeles. So I went to my best friend, Stanley Grinstein. Stanley and his wife, Elyse, were seriously collecting contemporary art, and I proposed to Stanley that we start an artists’ workshop, and we agreed to do it. In order to have a print studio, you have to have a printer. Ken Tyler had a shop he had started called Gemini Limited. It was a custom printing shop. In late 1965, the verbal agreements happened, and by the beginning of 1966, February, the shop was up and running.

JF: How were you able to attract artists initially?

SF: Gemini is an invitation workshop; we invited artists. Man Ray came to Los Angeles, for his retrospective at the County Museum, and he stayed at the Grinsteins’ house. He started coming to the workshop and just started hanging around. He even suggested to us that he do something. He did three editions with us. I think one of the early attractions was that California had palm trees, and the ocean, and the mountains. You’d come here, and you’d really enjoy your life; whatever it was, it worked. The first artist that really set the tone for Gemini was Bob Rauschenberg. He was the heart of what, in those days, was called the New York art scene. He was one of the young whippersnappers, and he was coming to Los Angeles somewhat regularly. He had his skating performances at Culver City, and he was a pal, and so he came out in February of 1967, and he did a series called “Booster.” He wanted to do a self-portrait of inner-man; that was the way he explained it. He wanted his whole body X-rayed. He asked me if I knew any X-ray doctors. It just so happened one of my closest friends from high school and college, Jack Waltman, was an X-ray doctor, and we went to see him. Bob wanted a 6-foot X-ray, one piece that he’d develop his print from. We found out that all X-ray machines are 1-foot, except there was one in Eastman Kodak in Rochester, New York that was a 6-foot machine. Bob didn’t want to travel, so he stayed here and had the six 1-foot plates made. Out of that, he developed his print called “Booster,” which became an icon of the print world and still is. Bob helped us get Frank Stella. And then Bob helped us get Claes Oldenburg. And then we invited Jasper Johns. We wrote a letter to Jasper, and he agreed to come out. Ed Ruscha was here locally, and he worked with us. I’m talking about the first three years of Gemini, 1966, ’67, and ’68. Ken Price worked with us during that time too, as well as Roy Lichtenstein. Within those three years, we had all these great artists working with us. It was fantastic.

Then shortly after that, Ellsworth Kelly. Invitation was always by phone call, or go see somebody, or a letter. I think, in a sense, a lot of times one artist helped us get another artist. If you asked the question, “How do we choose an artist?” a lot of times, we used the advice of an artist, or museum curators, or collectors. A lot of times, artists suggested people that we work with, and it’s been good for us.

JF: What was the idea behind making prints? Was it to make art more accessible to the masses?

SF: That’s part of what printmaking is. But truthfully we started it to have fun; we wanted to be around the artists. And so, once we got into it, and had all these accomplished artists around us, we realized the importance of it. I’d ask myself the question, “Why do artists make prints?” I felt that it was the accessibility of it. Many artists would do 6, or 8, or 10, or 12 paintings a year. These were very accomplished artists, and they would be shown in a gallery and somebody would buy the work, and it would never be seen again unless a museum would buy it. So here was a chance to make 50 of this or 35 of that, and they would be in galleries in Chicago, New York, St. Louis, Miami Beach, and Europe. They were very much interested in the idea of the fact that the work could be seen everywhere, and the same way it could be collected and people could own it in all these different areas. A lot of people think artists make prints primarily for money, and that’s not true at all. If they did drawings or paintings or sculpture in the time they’d spend at print-making, it would have been more financially profitable for them, but they loved the idea of these works being seen around the world, and they also enjoyed the challenge printmaking offers.

JF: At what point did you realize how important these artists would end up being viewed?

SF: In the early days, we really didn’t understand. When we started, Frank Stella was 29 years old, and Bob [Rauschenberg] was the old-timer at 39. We didn’t quite understand how important these artists were. It probably took at least 10 years, and then all of a sudden you start realizing, wow, you know, we’re working with the most accomplished artists of our time, and they’re already in the history books, and the interesting part of that is they continued to work in a very high quality for the rest of their lives. Even today, Ellsworth Kelly is 91. He’s been working here for over 40 years, as well as Bruce Nauman, Ed Ruscha, and Richard Serra.

JF: At what point did you realize that Gemini would be viewed so significantly in art history?

SF: I don’t know when exactly. It sort of just happened, the more we read books, the more we saw exhibitions, retrospectives, conversations, articles we read. Like I’d say to my daughter, “You go to a museum and what do you see?” You see Jasper and Bob, and Roy, Ellsworth, Richard Serra, and John Baldessari. And it just happens. I think by incidents, incident by incident, you realize it more.

JF: Why do you think someone should collect prints?

SF: I’ll answer in a different way. In 1968, I was in New York, and I called Jasper and asked him if we could go to dinner and he said, “Yeah, but we have to go to somebody’s house.” There were these famous collectors in New York, Victor and Sally Ganz; Jasper and I went to their house and I was introduced to them. I walk in the living room, and I can’t exactly remember the details, but let’s say there was a drawing by Bob Rauschenberg, a print by Roy Lichtenstein, a painting by Jasper, and then, around the room there were several paintings, drawings, and prints by these great artists. I looked around the room at the prints and they looked just as good to me as the drawings did and even though I’d been around prints, I hadn’t had that kind of comparison so directly. I was just thrilled to see that. It isn’t a matter of, say, if you put a print next to a painting or a drawing, and say, “Oh my God, that looks terrible, take it down.” It’s a different process. It’s different, but the quality of the print stood up so well. Another reason artists do prints is the challenge. You know, they’re in their studio every day, and they do paintings or drawings or sculpture, and they’ll come here once a year or every two years, and they have an opportunity to work with printers. It’s collaboration. It’s something that if they did this in printing last time, they want to do something else the next time. And they’ll try this, and next time they’ll try something else. It’s always a great experience. They probably have a better opportunity of experimenting here than they would, say, in their own studio.

JF: I’m going to name artists, and if you could, just describe them as you know them, whatever comes to your mind. Jasper Johns?

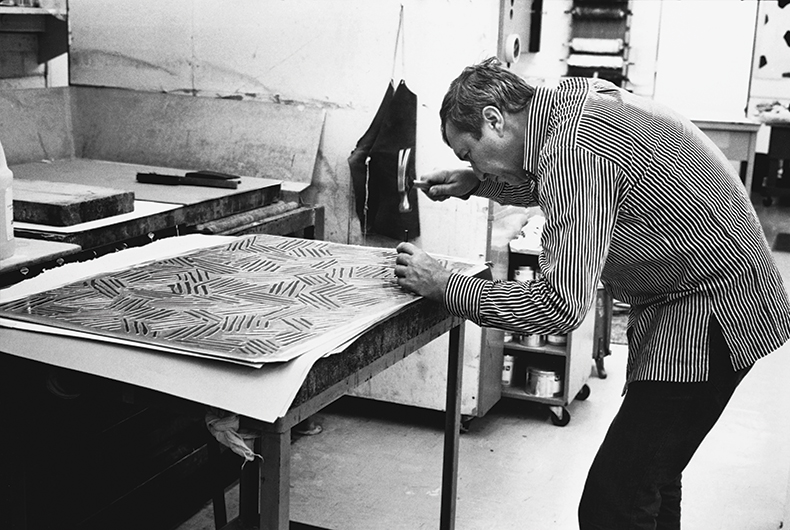

SF: Very hard working, very careful, tedious the way he works. He would bring a picture of a painting, a photograph or a drawing; he wouldn’t copy it, but he’d use it as a reference. He’d look at it once in a while and use it in his imagery here. The print was always different. His drawings were different, and his prints were different than his paintings, but there were similarities and references from one to the other.

JF: Roy Lichtenstein?

SF: Phenomenally precise. If Roy would say, in July, “I’m going to be out next February 2nd” he’d come on February 2nd, and he was really very serious about working the eight hours, no goofing off. He was always doing something, and he knew what he wanted. He brought all the studies that he made in his own studio. He would use an opaque projector, and he would expand up on a wall or screen the scale that he wanted, and [he’d] start working.

JF: Robert Rauschenberg?

SF: Phenomenally open and free; terribly creative. Bob reflected off of everything he saw or heard. And he never came prepared for what he wanted to do, but knowing in his mind exactly what he wanted. He would move with whatever the atmosphere was. Bob loved to have people around him when he worked. If he was in the studio, he’d have the TV on watching soaps as long as he could. He probably would ask us to hang around and talk to him while he was working and definitely listened to everybody. Terribly exciting.

JF: Ellsworth Kelly?

SF: Ellsworth needed privacy. If he were in the art studio, he would close the doors. You’d knock on the door, and he’d certainly let you come in and talk to him. But when he was actually working, he wanted his privacy.

JF: Frank Stella?

SF: Frank Stella, I had a great relationship with him. He’s a great sports fan, and he’s a tennis player. He was the youngest of the New York artists that came out here. He had done a few prints in school and was always excited about the processes.

JF: David Hockney?

SF: He was that British boy. David said he came to the United States and he turned on the TV and saw the Clairol ads, “Blondes have more fun.” So he went to the drug store and bought Clairol, became a blonde, and had more fun. David was something different for me in my life. His fashion fascinated me, and he was very much involved in society, worked very hard in the studio. If you go to David’s house, it’s like a Hockney painting. It’s red and green and blue, and he painted the house, everything about his life is about his life. He just sort of wove it together. Very exciting.

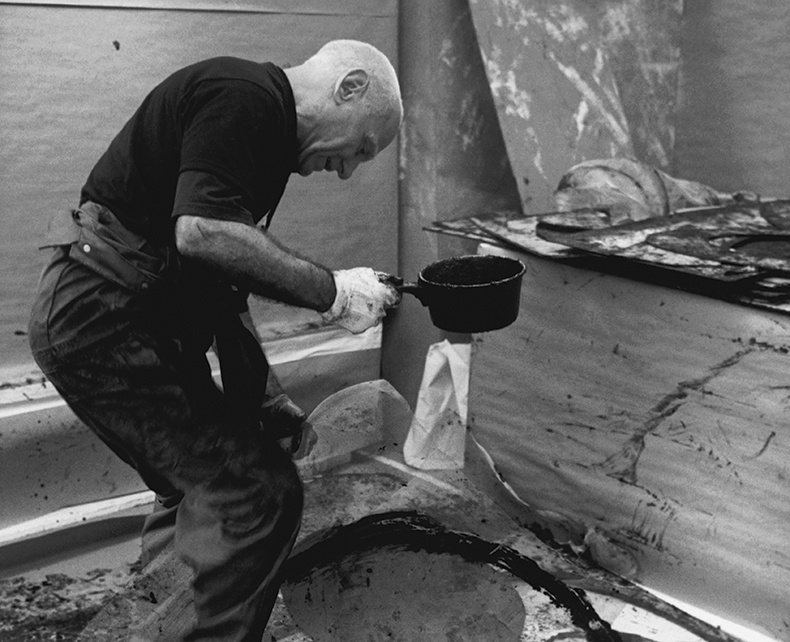

JF: Richard Serra?

SF: When he’s working, he’s like a steam engine; get out of his way. He’s probably 5’8” and he’s like a piece of steel. He’s just really, really, directly, “voom.” I mean that’s the way he works. And he’ll work for an hour or two and then he’ll just stop, and then he’ll just be very nice and ordinary and not so determined, but phenomenally determined when working. Exceptionally bright.

JF: Vija Celmins?

SF: Vija’s obsessive. If you look at her work, it’s all drawn. There’s no photography. It’s all little lines and marks that she makes. And she can spend three hours or two days with a piece drawing an ocean. She’s phenomenally dedicated to what she’s doing, and she talks about, “I have to learn how to make art easier for me.” And I felt, as the years went by, she probably made it more difficult for herself. She became more obsessive about what she was doing, but those drawings are so great.

JF: Claes Oldenburg?

SF: Claes is lyrical. There’s something about Claes when you look at his hand, the way it moves and the way he draws, it’s just beautiful to watch. And his voice, he talks like that. You know, he’s, I guess all these artists are magical in their own way, but there’s something magical about the way he creates imagery.

JF: Ed Ruscha?

SF: Ed’s cool, Mr. Cool. Phenomenally bright the way he creates imagery.

JF: Man Ray?

SF: He was tiny. You know, he was old when he was here, but I didn’t think of him being so old—he was so youthful. What I remember about Man Ray is that he had to give a talk either at Otis or L.A. County, whatever it was at that time, to the students. And he asked me if I’d drive him there, and he was phenomenal the way he connected to the kids. They just loved talking to him. He was really terrific. Afterwards we had sort of a correspondence. Man Ray lived in Paris then, and so I remember one time I just sent him a post card and just said, “How are you today?” He wrote back a note and said, “I’m alive from the waist up,” and that was it.

JF: Bruce Nauman?

SF: Bruce is great. Fairly quiet person, an athlete; Bruce was a really good basketball player. We’d have basketball games out here every day during the break periods. And Bruce, Frank Stella, Jim Turrell, and Richard Serra, they stood out as the athletes in the group. Bruce is sort of a mystical character and he is really rewarding to work with. He is a very good collaborator. The printers always feel they are part of his project.

JF: John Baldessari?

SF: John is the dean. If you go to a party where there’s a fair amount of young artists, they’ll come to John. It’s like coming to see the guru of your life, and they’re always so appreciative of what he taught them. Maybe what they’re really saying is, “Besides you teaching me art, you taught me about life, you really helped me in my own personal life, making decisions and understanding things.” John is 83 or 84 years old. He works every day. He has a trainer in the morning. He probably gets in his studio by 10 o’clock in the morning and works until 5 or 6 every day. He has five or six dealers who are always saying, “You know, I need more work.” He responds, and he doesn’t seem to ever be flustered.

JF: Do you have any advice for a young collector or young artist?

SF: This may be corny advice, but if it’s a young collector I’d say, look and make your decision slowly; don’t rush into something, but find something you really like. It’s important to ask questions, but I’d say go slowly.

JF: Any great lessons you learned from some of the masters who walked through these doors?

SF: My life changed a lot from being here, and it’s because of the artists. They’re such great people. You go to an art school; there are so many people that can draw a pretty picture. But artists that rise to the top generally are very intelligent. They could have been brain surgeons, or whatever you want to say the comparison would be. They’re all so kind. They’re concerned about humanity and about giving, and helping causes and just really being a better person.

—