“I feel I’m in a moment where people are really curious about what the next move is,” Theaster Gates offers, as I’m thinking, yes, tell me what’s next, what’s coming up? We are still early in 2015. I’m feeling as though I can still shape it. “Is he going to make a great work of art? Is he going to become a commercial artist? Is he going to retreat? Is he going to fail because actually we knew it was just a gimmick anyway?” he ruminates. I think it apropos that his first big museum exhibition was called To Speculate Darkly. “It feels good to live with a set of aspirations that are beyond the bet,” he turns the thought. “If nothing else, I could play albums to the babies so that they know who Thelonious Monk is. I am equally invested in playing songs to the babies as I am in my artistic practice,” he says laughingly but seemingly dead serious. Big questions aside, Gates emphasizes that the search is always to create perfect moments, poetic moments. “I want to imagine myself in the context of a moment and the context of a place with my ideas and see what that is all about.”

We caught up with each other as Gates was fresh off his second TED Talk and a couple months past his Artes Mundi 6 prize win, preparing next for his second solo show at the White Cube gallery in London at the end of April—Freedom of Assembly—and his participation in the Venice and Istanbul biennial exhibitions, in May and September respectively.

The TED Talk is a perfect platform for Gates—a hands-free microphone and a rapt audience of people who think as big as he does. “I was able to finally tell a kind of comprehensive story about Dorchester but also about the kind of impact that artists can make in the world—kind of beyond the practice, but in a way, we can only make the kind of impact we make because of the way we’re trained and the way we think.” Dorchester is Gates’ most well known gesture, performance and artwork, Dorchester Projects, which opened in 2009. It started with one abandoned two-story building converted into a library, slide archive and food kitchen. It is now a cluster of formerly abandoned buildings that have been renovated and rehabilitated to support and encourage redevelopment on Chicago’s South Side via the sharing of culture and ideas. Far from the Art Institute and the Museum of Contemporary Art, there were few cultural centers in the lower-income neighborhood.

“If we were to talk about the arc of a decade, the way that I started my TED Talk was by saying, ‘I’m a potter, and one of the things I learned pretty early in clay was that potters had the ability to make something out of nothing.’ And that the limitations of our sculpting were based on our hands and our imagination. So from the beginning I felt that the burden of transformation was always on me, and that it could only be as beautiful as I could imagine it and as I could build it. So if you were to carry that kind of vocational understanding through the next decade, then it was like—it went from shaping my house to shaping a block, to shaping city policy, to imagining that there was a model inside of this that meant that artists could shape the world.” And while some bad fools sling incredulous mud at Gates as if he were a prophet of trickle-down economics, the proof is in the proverbial pudding. Sure, the work travels the world to all the usual places, yet the beating heart stems from the streets of Dorchester on Chicago’s South Side. In addition to the international collectors on the art circuit, the city’s civic leaders are engaged.

“He had a vision on the South Side. And since we, as a city and as a country, have tried almost every other form of redevelopment, I said, ‘Why don’t we try the one that’s most obvious—the arts?’ Theaster has a commitment to his art and to the community that’s unique,” said Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel in a 2014 New Yorker article on Gates.

Like several of Chicago’s political leaders, Gates comes from a foundational experience with the church in early childhood. In addition to two degrees in urban planning, the artist holds a degree in religious studies. Liberation theology is understandably deeply embedded in his work. Gates’ art was included in Josef Helfenstein’s Experiments with Truth: Gandhi and Images of Nonviolence last year at the Menil Collection in Houston. The piece presented at Artes Mundi in Wales earlier this year—where Gates shared his (40,000 GBP) winnings with the other nominated artists—was titled A Complicated Relationship Between Heaven and Earth, or, When We Believe. That work sought to challenge Western ideas around Christianity, but Gates is level about specifics, and much more of a spiritualist. For the sake of the comparison, the art historical foundation for Gates in my mind is a cross between Joseph Beuys, Robert Rauschenberg and Doris Salcedo. “Art is not power for me. Do I believe in the power of art? Yes, but I understand that the power of art and the power to create is part of a larger power … All of this stuff is given to me through a rich spiritual muscle that I flex alongside artistic belief.” Whether he’s walking the walk or stumbling beautifully, Gates aspires to a spiritual character that is always genuine. He is quick to call BS on himself when something flies out of his mouth that he realizes after the fact is disingenuous or just plain wrong.

The music of the church is the music he feels. Early on when we met, Theaster and I were on a panel together with the curator Naomi Beckwith, who is also from Chicago. I was surprised by the fact that when it came time for Theaster to speak, he bellowed into a deep moody song that had definite reference in Negro spirituals. Naomi laughed as though she had seen this before, and eventually we both nodded to the gospel. Another significant part of his practice to date involves musical collaboration with the Black Monks of Mississippi, the experimental ensemble assembled by Gates in 2008. The Monks, with their obvious nod to “Eastern ideals of melodic restraint,” combine that with the “the spirit of gospel in the Black Church and soul of the Blues.”

“I can’t even call what I do singing,” says Gates. “It never had that burden. I think what I did was that I learned to talk. I learned to communicate beyond my body, and that was a training that happened every Sunday. Every Saturday at choir rehearsal, there were these notes and you had to memorize words, but past that you were learning to communicate emotion. So … it was the church, but the church is just a word—it was more like school. I’ve always said that I’m always just looking for the best language to communicate ideas, and in some cases, a material object is not the best way. Practice!”

“The Black Monastic” | Theaster Gates and the Black Monks of Mississippi perform during residency at Serralves Museum of Contemporary Art | Porto, Portugal (2014) | Photo by Sara Pooley | Courtesy of the artist

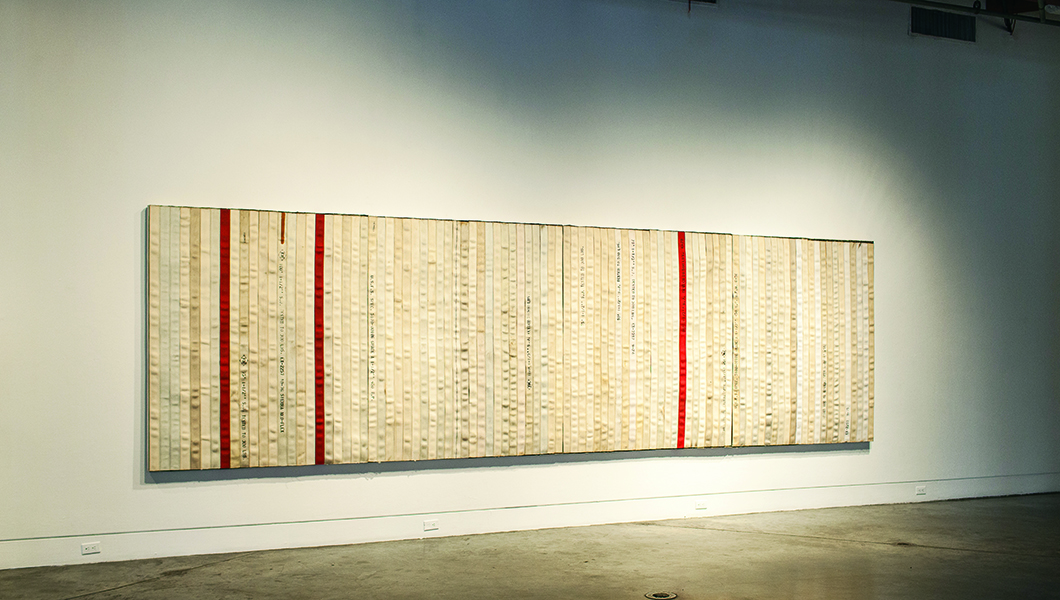

Work from Gates’ Tar Painting series (2014) | Installation view, Prospect 3, New Orleans

—