Much seems to have been made of the studio painter in the course of the past three years: Walker Art Center mounted a show (of largely abstract pictures) called Painter Painter; MoMA recently did its first painting survey in more than 50 years, The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World; and LACMA even tried to enter into the conversation with Variations: Conversations in and Around Abstract Painting. (Full disclosure: I co-curated that last one and Sterling Ruby was in it.) But if I think of Sterling and of his work, I would never imagine him as being part of that discourse. It is hard to find a more intellectually ambitious artist than Ruby.

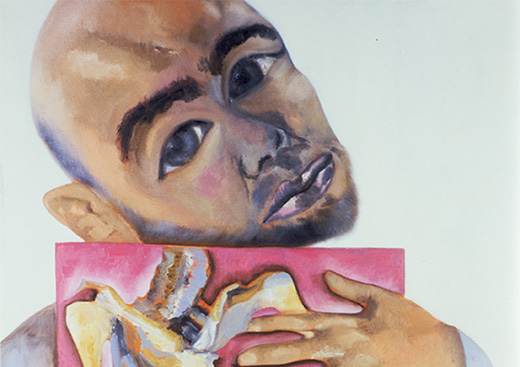

Well, no matter how much we all know and love that studio painter—the consummate artist of doing one thing really well over and over again with slight variation—we will always need the magician who can do it all! Art is the last place where alchemy and magic are actually expected. So Ruby makes use of all kinds of materials in a sincere quest to make magic objects that are hard or soft: Clay, Formica, nail polish, urethane and denim are some of his ingredients, to name just a few. He also works in video, sculpture and ceramics in addition to painting, in addition to collaborating with his friend Raf Simons on a fashionable clothing line.

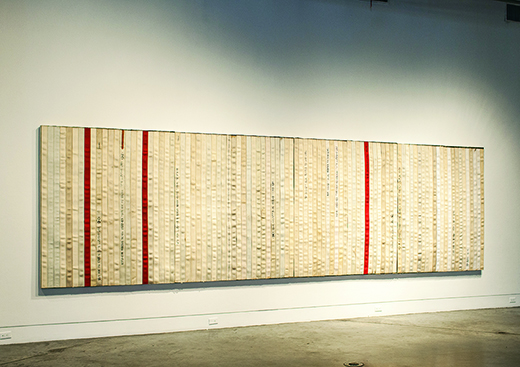

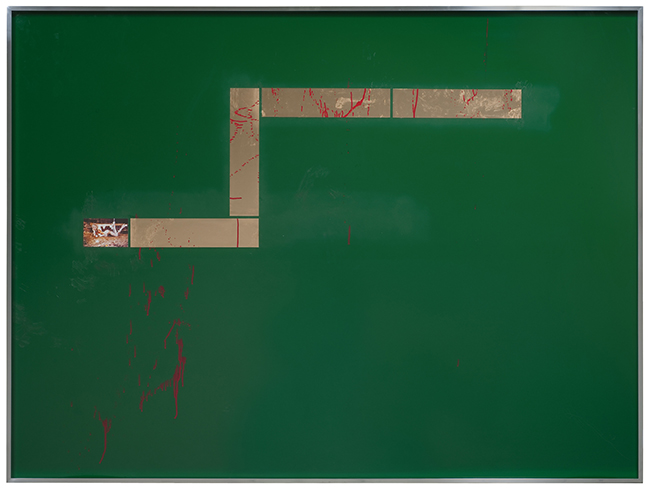

Ruby forces us to ponder big questions. To paraphrase Peter Schjeldahl from long ago, 1982 to be exact, Is it possible to “be radical indefinitely in any effective way?” Perhaps more to the point, is it possible to be radical and be a painter? And further, can one make abstract paintings that are the work of a radically inclined artist? Sterling Ruby does. He makes abstract paintings that recall Mark Rothko and Morris Louis, but there’s something amiss. Their tones and colors vary but they are all raining with drips of paint unlike that saturated into the surface. There’s the mark and the drip of spray that gives his paintings their tai-chi touch, recalling wall paintings and the preferred medium of the graffiti artist and writer. While they are usually all-over paintings with equal weight across the entire canvas, sometimes he uses black to outline space, creating either organic shapes or controlled blocks of color. Some recent ones are pinkish and pure candy-col- ored happiness. Others are brooding and dark. Some are clearly landscapes, filled with endless horizons. Sometimes I think Ruby makes the paintings bigger, as if to dare collectors to admit that they can’t afford to house such large works of art. Sometimes the really big ones conjure the feel of a wall and further recall the tradition of painting on walls under duress, when the drips are part of the process, intended or not. He calls those SP paintings. The Spray Paintings, of which there are approximately 300, are only one little piece of Ruby’s practice. It’s the most visible part of what he does, but it’s only a piece. If the paintings were all he did he’d probably be seen as an astute practitioner and one worthy of much success, but he wouldn’t be so special.

The surface demarcation of graffiti is something that Ruby has explored in great depth in another body of work, which consists of minimalist sculptures that have been colored like the paintings in some instances but also as simple cubes that are then tagged on by cutting into their Formica surfaces. Without going into detail on the works that involve Supermax prisons, which has been a major thematic in Ruby’s work over an extended period of time, one gets the sense that Ruby’s psychosocial space is not one of innocent wonder. His worldview is large.

Though born in 1972 in Germany to a Dutch mom and an American father, Ruby grew up in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, a rural area known for having a large Amish population. Sources online describe it as “a picturesque landscape. Rolling hills with lush landscapes and crops, farms with windmills dotting the horizon and horse and buggies sharing the road remind you that things are simpler here.” Things might be simple on the surface, but for the young Ruby, who saw the juxtapositions of the past and the present and the rural and the urban, it was a surreal place to grow up that provides a glimpse into the development of his art. Ruby absorbed his surroundings, in the country and in the cities, sensitive to the different sides of the tracks. “For me, it was about how as a kid I started to identify with visuals and aesthetics. The only culture I could get my hands on was surrounding me. It was where I grew up. I remember the landscapes of some Amish farms. They seemed drab, usually gray or beige, but then you see these super vivid quilts, kind of out of whack but also not. That’s the stuff that really drew me in, and I started identifying with the power of the visual in this context.” It also let him know early on that art had many contexts and was not only something for the museum. “ ‘Art’ is so narrow at times. It gets down to a very narrow group. I have a hard time with that.”

Not to say something so glibly, but the diversity of Ruby’s interests, matched by his materials, is perhaps unparalleled. His interest in art developed holistically out of the wonder of nature. Hunting and farming were familiar concepts. He attended an agrarian school before enrolling at the Pennsylvania College of Art & Design in Lancaster a year after graduation from high school, a year in which he worked construction. “They had an art history department but it was pretty steeped in Gardner’s Art Through the Ages. And I think that I realized about three quarters of the way through that in this day, that’s not really where or how good art happens.” In between adolescence and during school he also spent a lot of time in Baltimore and Washington, D.C., soaking up vastly different experiences as a curious youth open to that which was foreign. “In Pennsylvania, I often felt as though I were in a hostile, fascist community. It was so blind.”

When he moved to L.A. in 2003 in order to attend the MFA program at Art Center in Pasadena, he had recently earned a BFA from the School of the Art Institute in Chicago. But probably more important in terms of learning, he had worked at Video Data Bank in Chicago. Founded by the SAIC, VDB has been archiving video by and about contemporary artists since 1976. “That was my real segue into theory,” he says. Sitting alone in a room with the archive of archives in terms of contemporary video, Ruby would learn more than a few things on how to make good art. Imagine the combined holdings of the Louvre, Tate, Met and MoMA at your disposal every day in the same place if you are a painter.

Ruby is certainly no archetypal studio painter. But he’s a studio rat in the best sense, and his new studio is a big, living, physical archive space. He manages his own output on a desktop as we all do but he has also recently created a real living archive with the massive new studio operation. Works from his past are grouped according to materials and series, usually in a separate room. The new studio allows for presentations that approximate Ruby’s gallery spaces around the world, where the works debut to the public in meticulously thought-out juxtapositions. Walking around with him in the studio not far from downtown L.A. but far enough, you see his mind inspired by the work that has come before, as he dreams up new pieces to come.

—