MAKING BOLD STATEMENTS REQUIRES BOLD FILMMAKING AND AN OPTIMISTIC VISION.

Citizens of Humanity nurtures documentary short filmmakers to inspire global awareness and influence a course of action. Christy Turlington Burns and Roger Ross Williams both share this passion and bring the human experience closer to all of us in their new documentary shorts, no matter how much distance lies between. Model and advocate Turlington Burns has gone behind the camera to shed light on maternal health issues in the developing world as well in the United States. Her organization, Every Mother Counts, ran a 200-mile relay race to create awareness for mothers’ preventive health and wellness. Her short film, Every Mile, Every Mother, documents the experience and parallels the endurance of the runners to the women who have limited access to health care resources in rural areas of the world. Ross Williams is a seasoned documentary filmmaker whose experiences shooting heartfelt stories in Africa about the human experience have led him to create Tutu: The Essence of Being Human, a short film that examines the strength the Tutu family shares in its mission to fight racism and advocate peace through humanity.

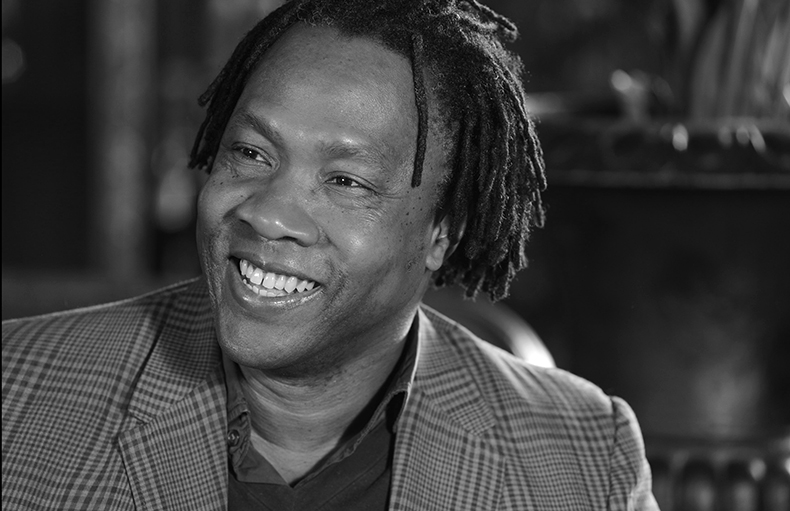

These two talented storytellers sat down together and discussed the challenges and blessings they encountered to bring light to stories set far from America that affect us all.

Christy Turlington Burns: I was curious when you said you almost chose [Malawi’s] President Banda for your film, how did you ultimately make the decision to go with Desmond Tutu?

Roger Ross Williams: Jared Freedman [of Citizens of Humanity] had already been talking to Tutu. They came to me with the project. But I had in my last film, God Loves Uganda, focused on faith leader Bishop Christopher Senyonjo, so there was that connection to the idea. When Jared saw that part of the film, he was like, “I really want that, what you captured from Bishop Senyonjo, to translate that to Tutu.” Tutu is very different, though, because he is such a public figure and press surrounds him all the time. He can’t walk out of the store without paparazzi around him. So it was very different, where as Bishop Christopher, he’s a private citizen. It was interesting with the Tutu media frenzy around him, which was a challenge in the film.

C: How big of a crew did you have?

R: I just had a South African production company. I had a South African producer, sort of a production coordinator, my DP from New York, and local sound. Just a small documentary crew. How about you? How did you decide to do yours?

C: Well, I have only made one other film. I made a documentary called No Woman, No Cry a couple years ago. It came out in 2010. . . . We filmed in Tanzania, Guatemala, Bangladesh and here in the U.S. looking at maternal health, the challenges and also the solutions in those countries. It’s funny, because I’ve wanted to make a documentary film for a long time, but it was only when I had a complication with my own delivery of my first child, I was like, this is the subject that I want to explore and I want to understand more what’s happening globally. Which women have access, which women don’t. It kind of grabbed me as a subject matter and then got me to take the risk to go into unfamiliar territory and take that journey.

R: I think documentaries have to be personal. You have to be passionate about it. It’s such a commitment; it’s such a long-term commitment too. That’s really what sparked me and sparked a lot of people when they make theirs, especially their first film.

C: Yeah, my husband is a filmmaker and he’s made probably four movies since I made my one documentary, so I got the sense of like, oh my god. It’s really like a child in the sense that it took me this long to be like, OK, I think I can actually start to make something else again.

R: Tell me about the film. Let’s talk about Every Mother Counts. How did you start that organization?

C: It started with the experience. I had this complication with my first child, who’s 10 now. I started to hemorrhage after I delivered her. I was in a birthing center here in New York City. I had a midwife, I had a doula, I was in the right place at the right time and they knew what was happening and they managed it the best they could. But in the weeks afterward, when I was trying to understand, how did that happen out of nowhere—like, why? Why me?—was when I came across the global figures of maternal mortality. I learned that my complication is often a cause of death for girls and women in a number of countries. Ninety-nine percent of them are in developing countries, but they happen here in the U.S. too. We have two deaths per day, and half of those are preventable as well. Once I learned the information, I had to know more about why. This isn’t one of those issues where we don’t know how to save the lives of women. It’s a matter of whose life has equal value or doesn’t. That part of it got me to want to do more. My mom’s from El Salvador and I’ve traveled a lot besides that, but I grew up going to her country, which also has a lot of issues around maternal health.

R: I’ve spent a lot of time in El Salvador.

C: I grew up going there quite a lot, but I went after I had my first child. I went back with CARE, one of the humanitarian organizations, while pregnant, with my mom, to El Salvador. That’s where I had the experience of traveling to a remote village and thinking if I’d had that complication here I probably wouldn’t have made it. Then going back and having my son and no complications and then really deciding then that this was an issue that, first of all, nobody knew it was an issue. I mean literally, I was shocked to find out women were dying. But I started to educate myself. I started traveling a bit with CARE and then also with ONE, just looking at maternal health in a number of countries. I then applied to Columbia University to get my master’s in public health.

The film actually just became a way that I thought. I was writing a column when I first started traveling with CARE for Marie Claire magazine, and I thought it was great to bring some of these stories of women that I’m meeting to life and closer to other women who otherwise wouldn’t get to travel. Then I thought those are great and useful, but film is such an incredible medium to really transport people and to really get someone to put their feet in the shoes of another human being.

The film became very clear. I just saw it. In Peru, I was coming back from a really remote area and thinking, this is my documentary film. I’m going to get out there, I’m going to look at this and examine this as an issue and hope that people want to see this. We were able to get a lot of people to learn about the issue from the film. It really has turned into an organization once I finished the movie. The film feels really good, and I think it’s going to make an impact. But then what? What are you telling the audience to do when people feel, like, how can I help?

R: Exactly. So that’s how you developed the organization? Because that’s really the big thing right now in documentary film is outreach and engagement around the film. Now it’s a whole industry. So now your budget for the film, actually your outreach and engagement budget, equals the budget of the film almost. And we develop pretty extensive campaigns. Now you have your film producer and we have our outreach and engagement producer.

C: Yes. Initially, we thought of it as a campaign, and I had it very much tied to the Millennium Development Goals. It came out in 2010 and I thought, OK, for the next five years I’ll use the film and my platform as best I can to get this to be a mainstream issue. But of course, after about a year or so, I thought, OK, that’s helpful, but a lot of organizations asked, “Can I screen your film? Can I raise money off of your film?” I thought, OK, yeah, that’s sort of satisfying, but not really that meaningful in the end. Not for me and also not for the audience that I’m touching. I think the audience was sort of like individuals like me who, whether they had a complication or not, they’d come through the experience. And just simply having come through the experience they felt connected and wanted to have that tangible connection with another woman and another mother. We really wanted everyone to come be that.

R: How did you decide to use the race as sort of the structure of this film that you did?

C: A couple years ago in New York City, we were invited to join the New York City Marathon as an organization. There was a dad in my kids’ school, “Oh you have a nonprofit? Would you like 10 spots for the marathon?” And I think he thought we might turn around and sell them or give them away in some kind of contest or something and I thought I know at least a handful of runners who would run this. And I kind of always had in the back of my mind maybe one day I’d run a marathon. So we responded and said, “Yeah we’ll take the 10 and we’re going to run it.” We were only three people at that time as a staff. So the three of us are definitely in, and then our next level of friends in our circle who are runners and could handle it, no problem. We started training and as soon as I started training—I wasn’t really a runner but had run up to four or five miles before, running and trying to increase my mileage a little bit. And I thought as all that time was going by, like, “I think I can, I think I can, I think I can.” But it also to me became really clear that one of the biggest barriers for women to access care is distance. I thought a lot of people raise money and awareness in marathon running. But for us specifically in our issue and how many women live in rural areas and can’t get to health care when they need it, especially in emergency situations, like that will be the way we communicate around this. Five kilometers being the minimum distance women have to walk to seek care; 35 kilometers is nothing, but it’s average probably for emergency transport. Just to get people again to put themselves in the seat of another human being.

So we ran it the first time. We ended up making it a team of 50 the next year because it was resonating with people, the idea that distance is a barrier. “Oh, wow, I can make that connection— women should have a ride or be able to have access.” So we got this opportunity to then run this 200-mile relay race. As soon as I learned about it, I thought what a cool idea. But it also takes that running metaphor that much further, because 200 miles is a very long way. Running as a team and thinking about how you really have to share this experience when one person is sort of losing energy, losing steam, you can switch them up and give us the support that we need to keep going. . . . I wanted to make a film of it but I wouldn’t have necessarily thought of making a film like this or finishing it this quickly. I would’ve thought, maybe we’ll shoot it and we’ll see what will happen down the line, but I didn’t have any real reason for it. When we started talking to Jared at COH, I said, “Well, we have this thing coming up that I want to film anyways.” He was like, “That sounds great, and that sounds interesting. Let’s do it.”

R: It’s great because you have a structure. You have a beginning and you have an end.

C: Exactly. And we want to inspire people to get involved. I hope that is ultimately what it does.

R: Yes, it’s very inspiring.

C: Had you done a short before?

R: I did a 30-minute short, called Music By Prudence, which won the Oscar in 2010. But I started it actually making a feature. I shot a feature and then I took it to HBO and I showed it to Sheila Nevins of HBO Documentary. Ten minutes and she’s like, “This is an Oscar short. It’s going to win the Academy Award.” She’s like, “Cut your feature and then you’ll see that I’m right.” They let me just spend six months cutting my feature, and I sat and watched my film and I was like, she’s right. I could do so much more. We could possibly win an Oscar, and then we did, which does so much unbelievably for the issue, which was about disability in Africa.

C: That’s incredible. The moral of the story—you finished it full length and then you reapproached it? That must be so hard.

R: It was painful because you’re just cutting out this and that, and you’re so married to this material. It’s like cutting your heart out.

C: Do you always work with the same editor?

R: No. Actually the last film, God Loves Uganda, is a different editor, an amazing editor, actually—one of the best in the business, Richard Hankin. I work with the same DP. Editors I sort of tailor it to the project. Some editors have strengths in one area and not in another. But God Loves Uganda is my first feature. This Tutu short my partner edited. . . . The great thing about making films is you get to meet people like Tutu, who is a hero of mine and a hero to many. Being around him was extraordinary. He’s such a down-to-earth guy considering everything he’s gone through and the history and the amount of people around him. He’s very moved when he talked about his life; it’s just amazing.

C: Yes, I loved that. There’s that old expression of behind every great man, behind every human, there is another who is making it possible for them to do great things. They, too, have made such a commitment to the world and there are a lot of sacrifices that they have to make. To see the impact not only on the world but also on his family—he has a very big family and a close family, but that’s just such an incredible thing to be able to get insight on.

R: He’s out being a person of the world and his wife is actually there in South Africa fighting that battle. What’s amazing about her is that she’s sort of different because it was his 80th birthday last year and he had his big party in the cathedral with Bono and Clinton and everyone, all his friends, and Richard Branson. She is a person who likes to be in the township with the people. She wanted to have her 80th birthday in this one-room church. All of the dignitaries have to come and cram into this one-room church because this is where she wanted to be. On the day of her birthday, she built a playground for the kids in this township who didn’t have a playground and she wanted to dedicate the playground and be with the kids on that day. She doesn’t want media attention; she doesn’t like the cameras. She’s just amazing—he actually teared up talking about her because she’s his rock. She’s the rock for all his family. He has three daughters and all of them do the work, they all do the work of Tutu, they all work in women’s rights and they’re all ministers and they all are inspired when they talk about their mother. Their mother was the real rock and, as he said, she is much more radical than he is.

C: I think it’s more common than has been told or shared over history. I think about Bob Marley’s wife, and one of his daughters wrote a song for our city and she also tells that story . . . he was off doing what he had to do, but she was really the rock and she was the one who’s still there, keeping the name alive.

R: Motherhood. There’s a theme. Strong, the woman behind the man, and it’s really behind motherhood for her. She raised pretty extraordinary daughters. Without Tutu—he wasn’t there much. I look at even Winnie and Nelson Mandela. She became very radical because she was in the streets fighting and he was away in prison. The women are the real sort of backbone of the clan and probably the world. Definitely in Africa.

—