Twisting and turning beneath the pavements of Paris is a surreal world known as the catacombs. A series of tunnels, wine cellars and former limestone quarries, it’s one of the oldest, densest underground subway and sewage networks in the world.

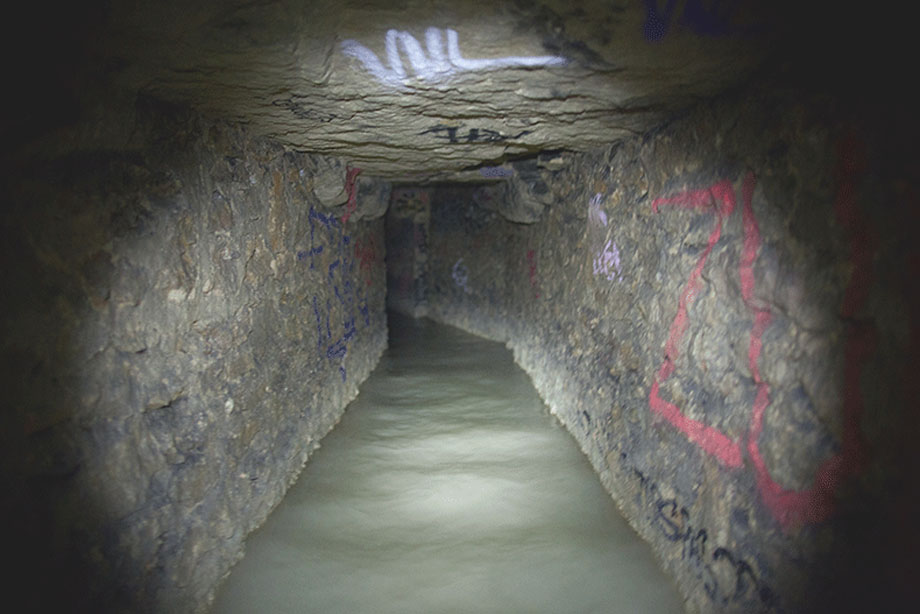

It’s a formidable landscape. Pitch black. Cold. Terrifyingly narrow in parts. Some tunnels are filled with thigh high, ice-cold water. In others, fresh sewage pumps into them daily. There are chambers stuffed with the human bones of over six-million Parisians, their corpses exhumed from Paris’ overcrowded cemeteries in the 18th and 19th centuries and dropped into the city’s underbelly.

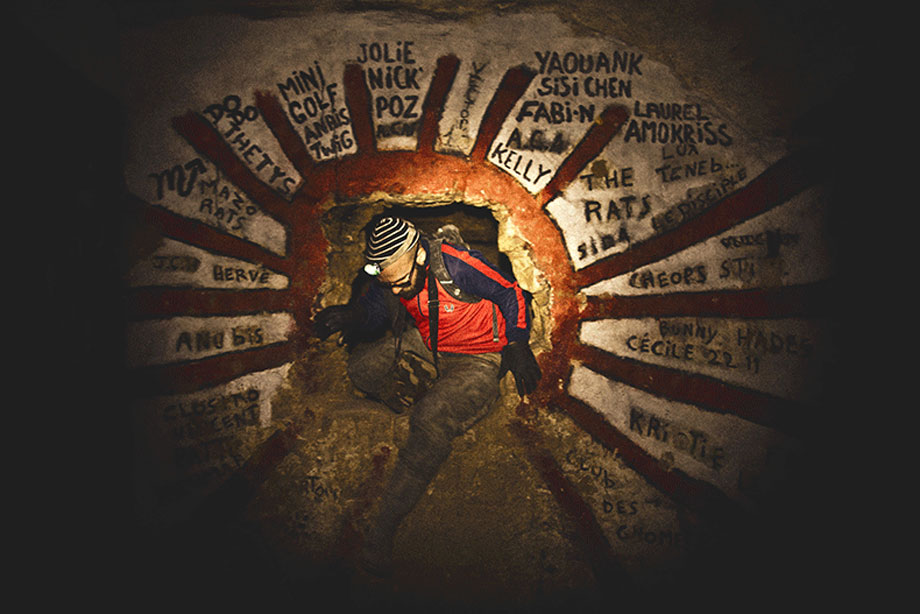

Despite these less-than-welcoming elements, a subculture of Parisians known as cataphiles are drawn into the tunnels. They emerge from manhole covers and grates bedecked in headlamps, rubber boots and caked in mud. The cataphiles range in age and occupations: Graffiti artists head down there to paint illicit tags; teenagers to party; goups of friends picnic at La Playa, a room large and airy enough for hanging out.

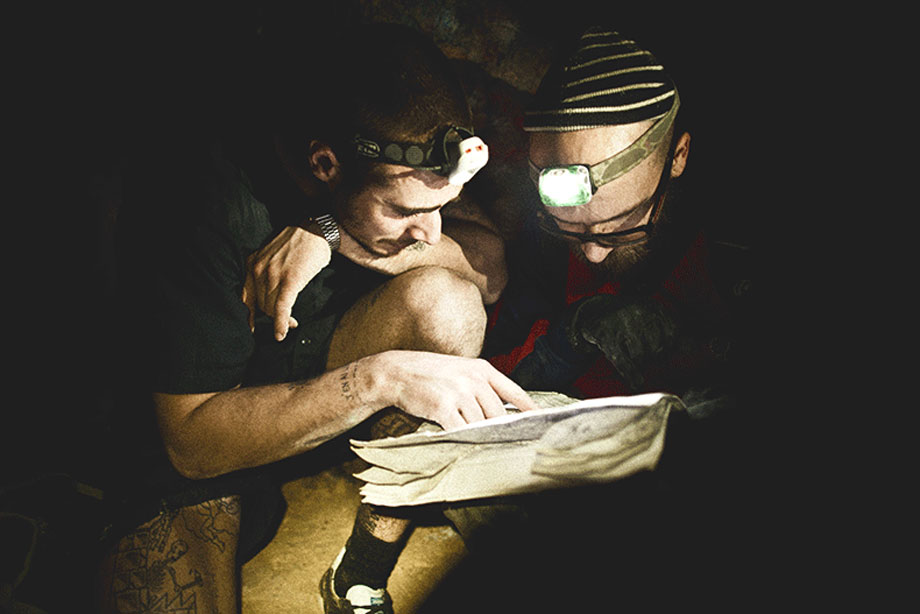

Not surprisingly, it’s illegal to go down there without a permit, but this doesn’t stop cataphiles from exploring the passages and tunnels to obsessive levels. Some mavericks take down diving equipment to investigate “black holes”—chasms of water nobody knows what’s at the bottom of—in order to map these forbidden chambers for their own personal gratification. There are maps available online, but they are often criticized for being wrong, out of date or missing information due to new discoveries.

The tunnels are not always safe and have been known to give way. A team of experts from the Inspection Générale des Carrières monitors them constantly, but as late as 1961, a collapse swallowed an entire neighborhood.

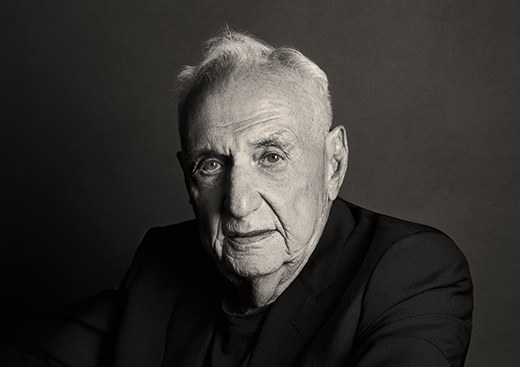

Despite these very real dangers, Berenger—a cataphile of two years experience who took Citizens of Humanity and legendary graffiti artist RISK on a tour of the tunnels—says once you go down it’s easy to become obsessed. “I cannot say how many times I have gone down. It feels like you’re discovering another world that ordinary people cannot imagine. I like to see the stones that support Paris, old tags and new, charcoal drawings that are 300 years old, and teenagers who are lost in every sense of the word.”

Like Berenger describes, the city’s history is imbued in the tunnels. Once upon a time, man and beast sweated over rock faces in the quarries. Farmers grew mushrooms down there, and during the Second World War, the French Resistance used them as did the German army. It was these layers—as opposed to the tunnels themselves—that made an impression on RISK.

“The thing that blew me away was seeing dates from a hundred plus years ago,” he explains. “It wasn’t even scratching the surface of how old some of the tunnels were. It was mind-boggling how many generations had passed through those tunnels, and how they have evolved over time. Those tunnels were used to execute people, secretly transport people, and now kids go there to explore and party.”

A one-off visit is one thing, but what kind of people fall in love with the catacombs and return again and again? “People who are curious enough to crawl down paths without any exits,” explains Berenger. “With patience and without fear, you can discover many interesting things.”

—

RETURN TO THE HOME PAGE

VISIT CITIZENSOFHUMANITY.COM