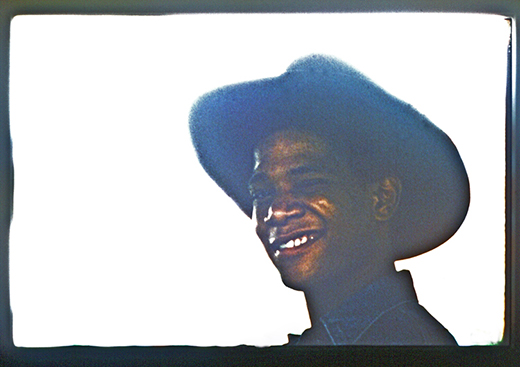

Artist John Baldessari has spent a lifetime using wit, intellect and imagination to create an art of ideas. An art teacher before he became an art star, he has trained generations of high-profile contemporary artists to take risks with convention, much as he has. He is today an international celebrity, recipient of countless honors, including most recently a National Medal of Arts, awarded last fall. The revered artist has exhibited in more than 200 solo and 1,000 group shows and at 85 is still usually found at work in his spacious studio in Venice, California, his 6’7” frame folded into a chair behind a desk cluttered with books, magazines and work in progress. There, using photographs, painting and text, he carries on and reimagines the conceptual-art tradition of Marcel Duchamp.

The studio is relatively spare but books are everywhere, from a Jackson Pollock biography to a book of short stories by David Foster Wallace. On the wall in front of him are several possible images for an exhibition next October at the Marian Goodman Gallery in New York, and at the far end of the wall a hat on a hook. “It belonged to Robert Downey Jr.,” Baldessari explains. “He said, ‘I’ll give you some art,’ and he gave me his hat.”

BARBARA ISENBERG: You’ve been creating art in Southern California since the ’60s, when Los Angeles’ place in the art world was very different. Being away from the limelight of New York, first in San Diego, then in Los Angeles, did you feel you could take more risks?

JOHN BALDESSARI: Well, that’s a good question. I think the risk-taking part of my life was when I was still living in National City, California. It’s a burg south of San Diego. Who’s ever heard of National City? It was beyond risk. Nobody was looking, so what did I care?

BI: When you started out, weren’t you a high school teacher, just having fun?

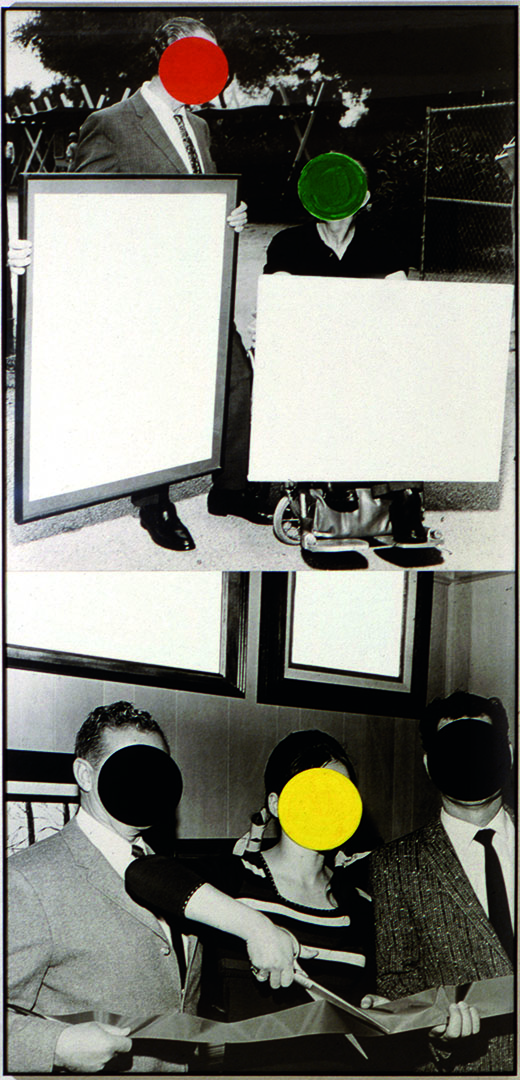

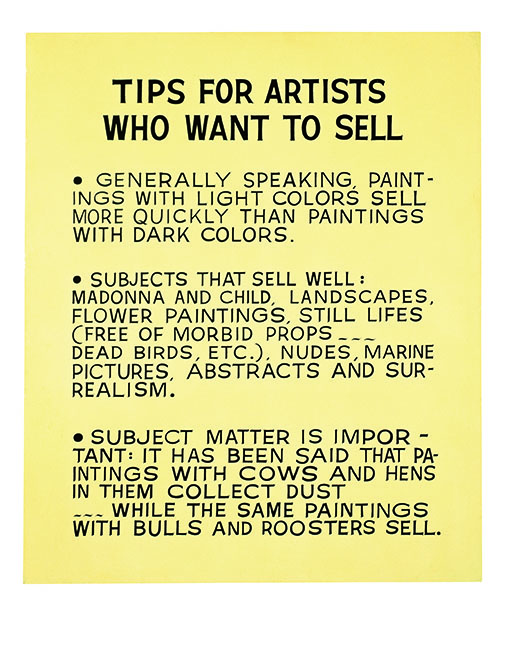

JB: Yes. Then one day in 1969 I was staring at this blank wall in my house in National City and thinking, “What’s the most bizarre thing I can do? I could make language the basis for art, get a canvas and have somebody else paint it.” And there you have conceptual art in a nutshell.

BI: You’ve come a long way from National City, exhibiting throughout the world ever since. You’ve also been based in Los Angeles much of that time. How has living and working in Los Angeles influenced your art?

JB: I always answer that question by saying that a shark is the last one to criticize salt water. If you’re immersed in something, you can’t see it.

BI: How is Los Angeles different now than it was?

JB: Things have changed. New York artists come out here and sniff around for shows. Europeans think of California as romantic, full of sunshine and palm trees; it’s cheaper to live here, and there’s better weather. In New York, you have more competition. I think it’s still more prestigious to have a show in New York than it is in Los Angeles, but that’s about it.

BI: Have you ever lived in New York?

JB: I was bicoastal for a while. I had an apartment in New York, but I couldn’t work there. I gave it up.

BI: When you were starting out, who influenced you?

JB: My touchstone is always Duchamp. I actually met John Cage when I was teaching at UC San Diego and he was in residence there. His book Silence was very influential to me. Philip Guston has always been a huge hero.

BI: Was Andy Warhol an influence?

JB: Absolutely. Sure.

BI: They have something in common, don’t they—Duchamp, Cage and Warhol?

JB: Well, a certain kind of irreverence. If you think about Warhol’s main reputation at the time as illustrating children’s books, and someone told you that he would become such an iconic artist, you’d say “No chance.” But he was a very social animal, and he wanted attention.

BI: When you look around at artists you’ve taught over the years, so many of them went on to distinguished art careers of their own, such as David Salle, Barbara Bloom, Matt Mullican and James Welling. Do they influence you?

JB: Among the smartest is David Salle, who was one of my students at CalArts. He writes very clearly about art on interesting topics. David influences me.

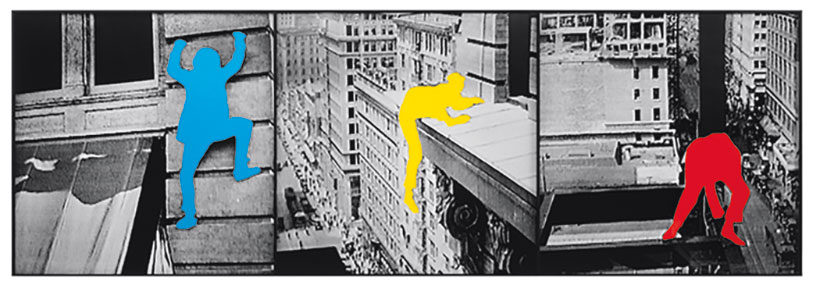

BI: What has captured your attention lately?

JB: I’ve been very much influenced by Jackson Pollock and Thomas Hart Benton as his teacher. I haven’t gotten very far, but that’s what I’m working on now. The show will be painting and text.

BI: You’ve said many times in the past that the word and image are pretty much equal to you. Is that still the case?

JB: Yes, I still believe that.

BI: Yet what you do with the words and images keeps changing.

JB: Artists are artists because they don’t want to do the same art they’ve been doing, so they keep on pushing forward and experimenting. I keep on changing the work, and it will keep on changing. I don’t know how it will finally look. I have no idea.

BI: You told me once that you never wait for inspiration.

JB: It’s interesting how the mind works. I’m grappling with new work, and I sort of put myself to sleep trying out certain combinations in my mind, juxtaposing work by Thomas Hart Benton and Jackson Pollock. Quite often, like most good ideas at night, they’re rotten ideas in the morning. But I can’t think of nothing. I think it’s impossible to have a blank mind, so different things flash on your screen. Most of the time, it gets to this: If I were in my studio now, what would I be trying to do with these artists?

BI: You’ve also been buying art for the first time recently. How did that start?

JB: A painting by Giorgio Morandi was the first one, and it was instinctual. I was in New York, at David Zwirner Gallery, looking at things, and I just fell in love with it. I asked the price. He told me—I gulped, but I bought it.

BI: Well, that’s what money’s for.

JB: It is actually, in a way. Do you remember David Platzker? He used to work for me. He’s now a curator of drawings and prints at the Museum of Modern Art, and I figure more people would see a work there than they would in my studio. So I’ve bought certain artists’ works and just given them to him. When he’s looking for something, he’ll call me and ask, “Would you be up for buying this?” I thought it was better to give art away so more people could see it.

BI: Do you think of it as a way to give back?

JB: Yes, I think so. It’s a good use of money. I also have a foundation, and there are good people on the board. I said, “You give money to whoever you want. I trust you, and that’s why I have you on this board.” Last year we gave around $500,000 to artists and artist spaces, and I feel pretty good about that.

BI: So you’re buying art for yourself and giving away art?

JB: What else would I do with the money? My children are provided for. I’m building a Frank Gehry house.

BI: Does your fame get in the way of your art?

JB: Probably, in a bad way. The analogy is to somebody in prison. His natural instinct would be to try and escape, but if you treat him really well and feed him really well and give him better housing, he might think, “Why would I want to leave?”

BI: Do you ever think about your legacy?

JB: There’s a certain satisfaction to knowing you’re embedded in the history of art. I feel part of a tradition.

—