A successful artist’s work nearly always survives beyond the artist’s death—but how do you actively preserve, and perpetuate, their ideas? Take pioneering rule breaker Robert Rauschenberg, whose artworks from the 1950s through to the early 2000s questioned the very meaning of art. Like the blank canvases he called his White Paintings (which were said to have inspired fellow Black Mountain College alumnus and close friend John Cage’s silent musical score, 4’33”), his collages made from Moroccan trash (the ones he didn’t sell he threw into a river), his stuffed goat or his blank piece of paper with the self-explanatory title Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953), an artwork said to have taken him one month and 40 erasers to complete. When Rauschenberg died in 2008, leaving behind him a legacy that existed not just in museums but in people’s inspiration, the question was, how do you caretake a vision once the visionary is gone? How do you ensure that ideas live, breathe and continue to evolve?

The task was entrusted to a woman named Christy MacLear, who, as head of the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, is dedicated to keeping not just the work but the ideals of Robert Rauschenberg alive. “What we do is defined singularly by the values that we have defined, and those values were defined by the people who were closest to Bob,” says MacLear. “So it’s not just that we give grants, it’s that we give grants to things that are fearless, that are creative problem-solving, that are global-minded and interested in peacekeeping across borders. We will fund projects that may fail because we are funding risk-seeking or catalytic types of moments in an artist’s career.”

The foundation provides a sanctuary where artists can push the boundaries of their own vision, à la Rauschenberg. Rauschenberg’s former home and studio on Captiva Island off the coast of Fort Myers, Florida, is now a 20-acre compound accepting 10 new artists every five weeks from varying geographies and disciplines. And the rest is up to them. “They get to come in, they get a house, they get a studio or a dance studio or a sound studio and they get to work on their artistic practice,” says MacLear. “We don’t expect anything to come out of it and we don’t ask them to give us anything in return. What we find is that most artists come in and with that degree of liberty, they actually expand their artistic disciplines. We find that with that open space for their creative practice, they interact and try something entirely new.”

Performance artist Laurie Anderson is an alumnus—as are many emerging artists. Some go on to become well known for their art, some don’t. While on Captiva, they are all rewarded equally, though. Rewarded for being risk takers and fulfilling the foundation’s goal of seeding new generations of rule breakers—artists after Rauschenberg’s own heart.

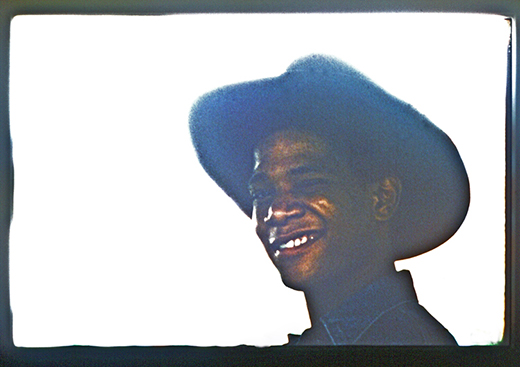

Robert Rauschenberg is one of the most influential artists of the last half century. He also happens to be one of the most missed. Instead of trying to explain this, we sought out those who knew him best to share insight into what made him the father, friend, and artist he was.

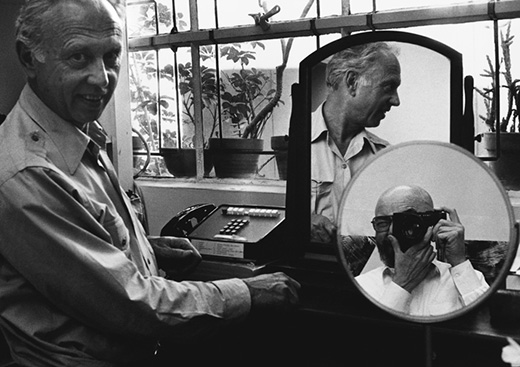

“I think Bob is one of the greatest artists that ever lived, but it was his intelligence, his sense of humor, his concern for everyone else, his practice of philanthropy, his willingness to give and give and give that made him the GREAT MAN he was.”

Sidney Felsen

I’m at my dad’s house in Captiva. He has chosen to come home from the hospital and has spent the last few days of his life in his studio. I have read the excellent obituary of my father by Michael Kimmelman in the online NY Times, but then Bob’s secretary, Bradley Jeffries, tells me to go back and read it again. I ask why and he tells me to look at the comments. There are over a hundred comments and virtually all of them say either I never met Bob Rauschenberg but he changed my life or I met Bob Rauschenberg and he changed my life. Of course, as Bob’s son, people have been telling me all my life how much my father’s work meant to them, but when he has just died and I’m wrestling with the idea that he is gone, it has a whole new meaning to have over a hundred people step forward and say that he’s not gone. To have over a hundred people come forward and say that they have incorporated his spirit, his work, his generosity and way of looking at the world into their own spirit, their own work, their own generosity and way of looking at the world–at that moment that is a magically wonderful thing for me.

The Robert Rauschenberg Foundation is, for me, all about this idea that Bob is not gone. It gives us a chance to keep organizing shows of his work to keep blowing people’s minds; it gives us a chance to fill his studios with 70 artists per year who are pouring out great work made with great excitement; it lets us keep his philanthropy flowing. It lets us keep creating people who can say I never met Bob Rauschenberg but he changed my life.

Christopher Rauschenberg

A dealer owed Bob quite a sum of money. Desperate, Bob was able to obtain a court order and was finally paid. “What then?” I said. And Bob’s response was, “I gave him another show!”

Irving Blum

Knowing Bob had a big impact on my life. He was a true artist. He had a huge gravitational pull and held himself to a higher standard than anyone I’ve ever met. Bob defined integrity. If the rest of us could exist at his level the world would be perfect.

Chuck Arnoldi

All I have to do is sum it up in two words: Brilliance and generosity. I miss him deeply.

Laddie John Dill

About twenty years ago I received an extraordinary birthday gift from my wife Stacey. She had called Robert Rauschenberg and told him what my favorite colors are, my favorite things, and Mr. Rauschenberg made a collage of my life.

That piece of art hangs on our wall and gives me pleasure every day. It is green. It is white. It is fierce, and at the same time, dreamy.

What an honor it is to have Mr. Rauschenberg in our house.

Henry Winkler

I think of Bob often. One thought that regularly comes to mind is we should have put a recording device on him for 90 days; it would have produced material for one of the great philosphy books ever written.

Suzanne Felsen

When I think of Rauschenberg what comes to my mind is the Gluts series (end of ’80s to beginning of 1990s). I believe it’s the most actual works he made in their form and content and that they are very influential to artists working today.

The form of the Gluts wall or free-standing works, the way they are made, is in the tradition of the assembled found objects used directly in a sculpture or painting that was invented in the early 20th century by Duchamp and Picasso. Rauschenberg’s famous Combine paintings were already in that lineage, related to the invention of the collage by Picasso and Braque.

The content, the meaning of the Gluts has a strong resonance today, even if for different reasons than at the time Rauschenberg did the series, when there was a glut in oil, and he used gas station signs, industrial parts in metal …

Almine Rech

I am blessed that I knew him and his work.

Frank Gehry

Bob was the Walt Whitman of 20th Century American art. His name was Bob, by the way, not the professorial Robert.

Dave Hickey

Bob had this international inquisitiveness and enthusiasm, thinking that art was this universal language that could be accessible to everybody, as opposed to a verbal language.

David White

Robert Rauschenberg had a restless mind … an unstoppable imagination. It’s hard not to be envious of someone who wakes up and asks himself, “What shouldn’t I do? I think I’ll do that.”

Mikhail Baryshnikov

Bob was a generous spirit, always helping others, an upbeat person.

Once I was having dinner with Bob in Baltimore. After dinner we went to MICA [Maryland Institute College of Art]. We went to the artists’ studios at MICA, where three or four students were working, and Bob spent more than an hour critiquing their work.

On another occasion, my wife and I were visiting Bob in Captiva. We were staying in his guest room, where the bed was too soft for us. Bob gave up his room and his bed for us to be more comfortable during our visit.

Another thought: When we visited Bob, he always had the television on while he was working.

Robert E. Meyerhoff

I think of the endless thought provoker from Port Arthur, Texas, who visually continues to invent and rearrange the most extreme thinking with positive expansiveness.

James Rosenquist

I always knew that when I was going to see Bob there would be a lot of laughter. There was this thing he had about connections. Whether they were complex, simple, nonessential, existential or even silly, Bob got a giant laugh about connections. It was an infectious, joyful, “aha!” kind of laugh. When I wasn’t completely clear about a connection, he would bring me along with a laugh that was more than just about the irony or humor of the thing. He could make me see the point.

A long time ago I spent a week on Captiva Island at Bob’s studio, fishing, playing poker and ignoring the clock. Jim Rosenquist was down for the week and the conversations were, in my mind, epic. I was 27 at the time, so everything those guys said was epic to me.

One morning Bob invited me into his painting studio and pointed to a very large canvas he was working on and said, “Why don’t you think about what should happen on the bottom right side where I’ve already started, and I will work up here on the left.” When I got past the initial shock of the invitation, I did work on it. I did because it was clear to me that Bob considered my art-marrow to have a connection with his, just as he considered so many artists as having that connection. I think he thought, “Why not try it out with Guy?”

Years later I asked Bob what happened to that big canvas. He told me it got much smaller; he thought it would work better as a drawing on paper. Nothing about the bottom right, though.

Guy Dill

Robert Rauschenberg was already beset by physical setbacks when I met him, but he was animated by an outsized curiosity and love of being alive. He was interested and engaged in everything that met his eye, and his interaction with the world, his avidity, was inspiring. Knock on wood, I thought, I have all my capacity, my heedless good health, I can still jump and run, but I have HALF his energy, his verve, his eagerness in living. That was a lesson to me, every visit with Bob lit a fire under my complacent butt.

Meryl Streep

—